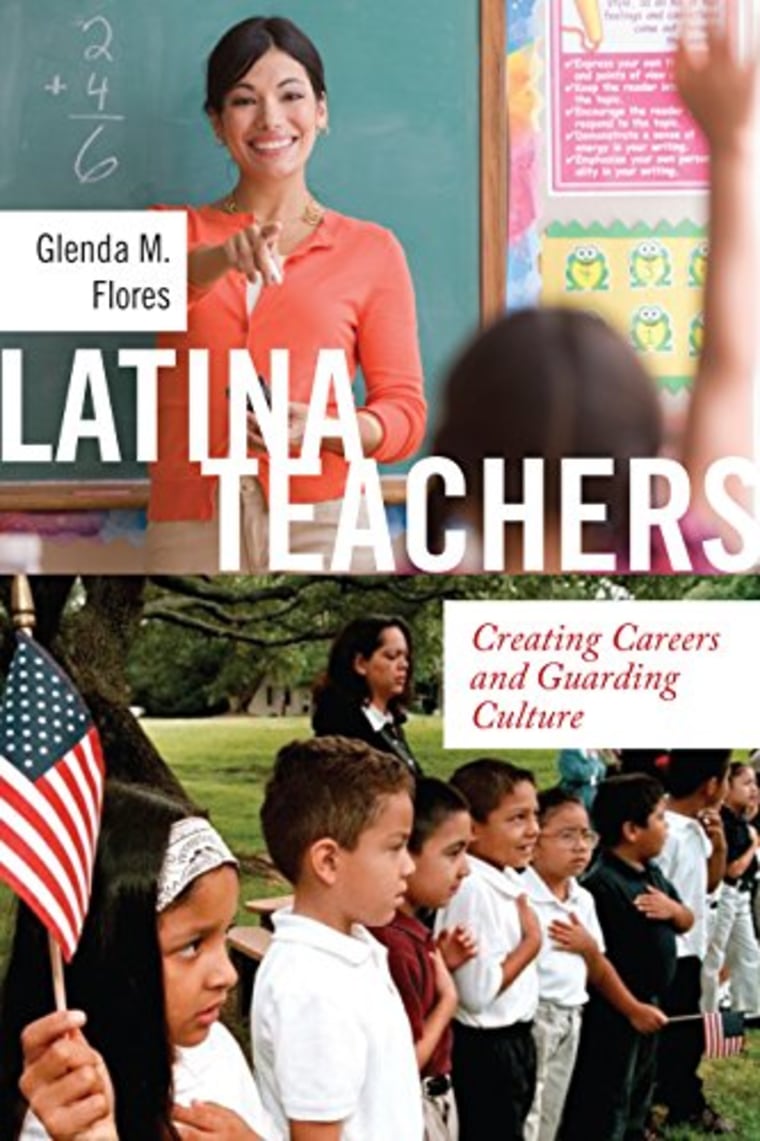

The growth of the Latino population in the United States will have a lasting cultural and intellectual impact beyond the arts, food and celebrations. More and more, it's Latina teachers who our shaping our classrooms and our children's education, argues Glenda Flores, a sociologist in the Department of Chicano/Latino Studies at UC Irvine.

In her new book Latina Teachers: Creating Careers and Guarding Culture, Flores' research shows the impact of the growing numbers of Latinas who are going into teaching.

Latinas in education make up the largest category of Latina professionals, outpacing the next largest category, nursing, by three times. Data from the Department of Labor shows that Latinas make up the fastest growing non-White group to be entering the teaching profession.

Flores writes that the influx of Latinas in education comes from a confluence of historical and social factors she calls the class ceiling. Difficulties in balancing family obligations along with managing structural social forces of gender, ethnicity, and demographic changes channeled Latinas into education.

Women of Latino origin are more than 18 percent of teachers in California, creating a "Latinization" of the profession, whereas they were once a token of the profession in the 1980s.

Beyond the language barriers that Latina teachers help bridge are culture-specific pedagogies that go unappreciated when the teaching population is not diverse. One aspect Flores brings attention to is children with immigrant parents who seek help from their parents on their math homework. Mathematics, says Flores, is not a universal language, and approaches to problem-solving in division and multiplication, for instance, often differ in the United States than they do in Mexico. Immigrant parents who were trained to solve problems using different techniques, Flores found, were hampered when trying to help their children. Latina teachers, however, were able to recognize this from their own experiences with math and were more open to alternative methods that ultimately served the students better.

Emma Cadena is a self-identified Latina teacher born to an Irish mother and Mexican-American father. Her blond hair and green eyes may seem out of place in Santa Ana, where Latinos make up 78 percent of the population and have an all-Latino city council, but Cadena was raised by her father in Santa Ana. Her classroom is adorned with lessons in Mexican culture, from the Diego Rivera painting on her classroom wall to her ensemble of Mexican crafts, including Day of the Dead skeletons and a Lucha Libre mask. Cadena also hangs a poster of Cesar Chavez in her classroom, the civil rights leader who helped lead the struggle to unionize farm workers in California and a reminder of how Latinos have shaped our national history.

California has gone through a demographic transformation since the time of Governor Pete Wilson's infamous politicization of immigrants through Proposition 187 in the 1990's, the law that institutionalized citizenship screening processes for access to public services, such as education.

Latinos now make up 52 percent of all K-12 students in California. According to Pew Research, 64 percent of the Hispanic population in California is native born. Astonishingly, the median age of this group is 19 years, less than half the median age of foreign-born Hispanics, which is 43 years old. The median age of non-Hispanic whites in California is 45 years old. In other words, despite any future walls on the border with Mexico, it won't do much to prevent the Golden State from turning a golden brown.

While California was going through rapid demographic changes, the need for bilingual teachers also grew throughout the 1980s and 1990s, until bilingual education was eventually banned by law in 1998. However, the demand for these teachers, along with the shifts in population, had created a perfect storm of sorts that established a pathway for Latinas into the field.

California recently reinstated bilingual education with the passing of Proposition 58, ending the English-only teaching era that is sure to continue California's transformation. Today, California students are twice as likely than other Americans to speak a language other than English, at 45 percent.

Flores says she became interested in education, because growing up in Santa Ana she too thought about becoming a bilingual elementary school teacher. However, as she continued her education she got a Ph.D. at the University of Southern California and began looking at statistics, noticing the trends in Latina teachers. She began her research to see how these trends were impacting students and her research landed her a job as a professor at UC Irvine's Department of Chicano/a Studies.

Recent headlines have focused on the political gains made by Latinas — in Virginia, Elizabeth Guzmán and Hala Ayala recently made history as the first Latinas elected to the state's House of Delegates, beating Republican male incumbents. Latinas made headlines in Santa Barbara, CA and Topeka, KS as well; Cathy Murillo became the first Latina mayor of Santa Barbara and Michelle De la Isla the first one in Topeka.

But leadership in government is not the only sphere impacted by growing numbers of Latinas running for office. Flores' research in Santa Ana, CA illustrates that our children's formative years will be increasingly shaped by Latinas, as well.