MIAMI, Fla. — When playwright Rebecca Aparicio was commissioned to write a children’s musical based on a Latino fairy tale, she was at a loss.

“The producers were interested in my experience as a Cuban American and I did the research but no fairy tale or story quite interested me until I came across a website about Operation Pedro Pan," Aparicio told NBC News. "And all of a sudden I realized, I know this story!”

Rather than a fairy tale, she had stumbled on a piece of seemingly fantastical history that is getting new examination amid the turmoil wrought by the Trump administration's separation of thousands of children from their parents and guardians as an anti-illegal immigration tactic.

Between 1960 and 1962, desperate parents afraid that their children would become wards of the Cuban revolution after Fidel Castro's rise to power, sent 14,000 children to the United States through Operation Pedro Pan, a program operated by the Catholic Welfare Bureau (Catholic Charities) of Miami under the guidance of Monsignor Bryan O. Walsh and the U.S. State Department.

The children, who arrived without their parents, either lived with family members if they had any in the U.S. or lived in Catholic Charities orphanages or foster homes. For some children, it was years before they saw their parents again.

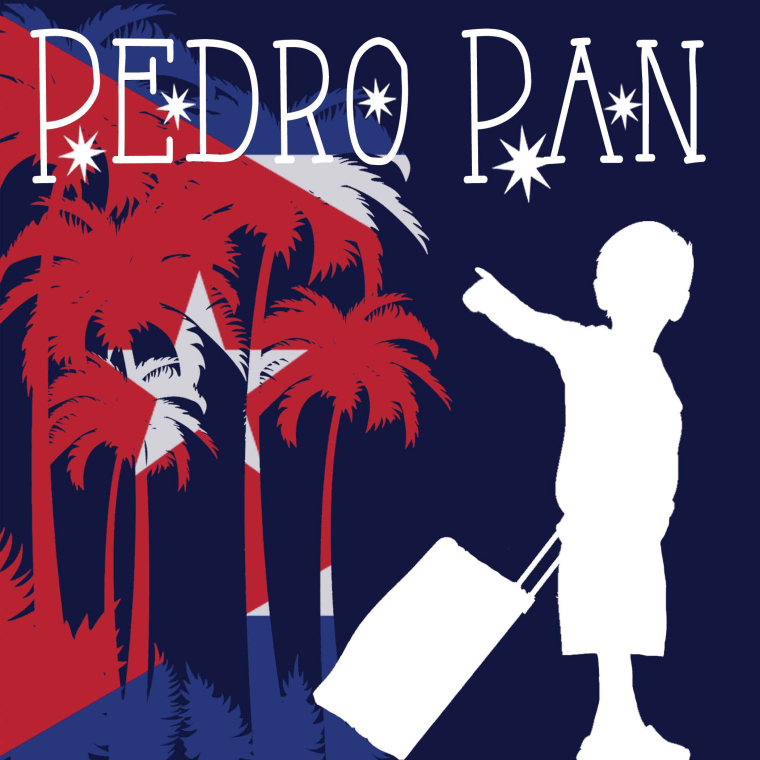

Although both of Aparicio’s parents had come to the United States as young children — with their parents — she used their profound love for their adopted country, along with the many challenges they faced, as a starting point for her musical, "Pedro Pan."

“I was very familiar with why they had to leave Cuba, making that journey, and what their immigrant experience was like here in the U.S.,” Aparicio said.

“I felt I could really shed a light on this historical moment that even I as a Cuban American wasn’t aware of," she said.

Delving into Cuban American history helped Aparicio deepen her relationship to the immigrant experience, educate people on what it’s like to flee a country under Communist rule and theatrically examine what it means to be a displaced immigrant in America.

Although families willingly separated from their children in the Pedro Pan program while those on the border were forced, Aparicio found commonalities in the different events.

“The idea of personal sacrifice as a parent, doing whatever it takes for the safety of their child, and then the trauma of the child having to be without the parents — even if it’s the best decision for the child and for their safety — the emotional effects that it has on the child, is something that resonates with any human being," Aparicio said. "You can’t not be moved by thinking of a child navigating the world almost on their own.”

Many of the children the Trump administration separated from parents or guardians have come from Central America and their families were seeking asylum. They arrived to the border with horrific stories about violence, drug cartels, gangs and extreme poverty in their home countries.

"Pedro Pan" revolves around a young boy who is sent to the U.S. to escape the growing dangers of post-revolutionary Cuba. To survive, Pedro must learn a new language and culture while hoping to one day be reunited with his parents.

The musical was named one of the Top 10 Off-Off B'way Shows in 2015 and currently is part of the 15th Annual New York Musical Theater Festival.

Aparicio hopes the musical will help audiences empathize with immigrants, regardless of the opinion they hold of the administration's zero-tolerance policy that led to the separation of 3,000 children from their parents or guardians. The administration has been forced by a court to reunite the children families, as long as there is no concern doing so would put the child in danger.

“There’s an idea that you can't be sympathetic and have opinions about the law. They don’t have to be at odds," said Aparicio.

"We can be at odds about immigration law and not be at odds about children being separated from their families. However you feel about immigration law, I totally validate that and we can have a discussion about it," Aparicio said.

"But for children to be separated from their parents, I think we can all agree that that’s wrong. I think that seeing that experience reflected on a stage can create some empathy," Aparicio said. "You’re tied to your community, but you have to stand up for what’s right.”