It was a smoggy day Aug. 29, 1970, when journalist Ruben Salazar, 42, went to cover a gathering in East Los Angeles. Billed as the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War, the event was held to protest Mexican American casualties in the Vietnam War. An estimated 30,000 people marched that day, in a largely peaceful gathering. But once law enforcement moved in, in response to reports of vandalism, the rally devolved into chaos and violence.

By the end of the day, three people were dead, including Salazar, the most prominent Latino journalist of his day. He died after being struck by a tear gas canister fired by a L.A. County sheriff’s deputy.

Fifty years after Salazar’s death, Latino scholars, journalists and activists still honor his legacy. His killing sparked outrage, activism and sorrow, while his memory inspires pride. Not only was Salazar’s death a seminal moment in Mexican American history, but also the issues that mattered to him remain relevant today.

“Salazar was an ordinary man who believed that it was his job to tell the truth. He believed in the First Amendment, and I hope for young people there is something about his decency and integrity that they can take away,” Phillip Rodriguez, producer and director of the 2014 documentary “Ruben Salazar: Man In The Middle,” said.

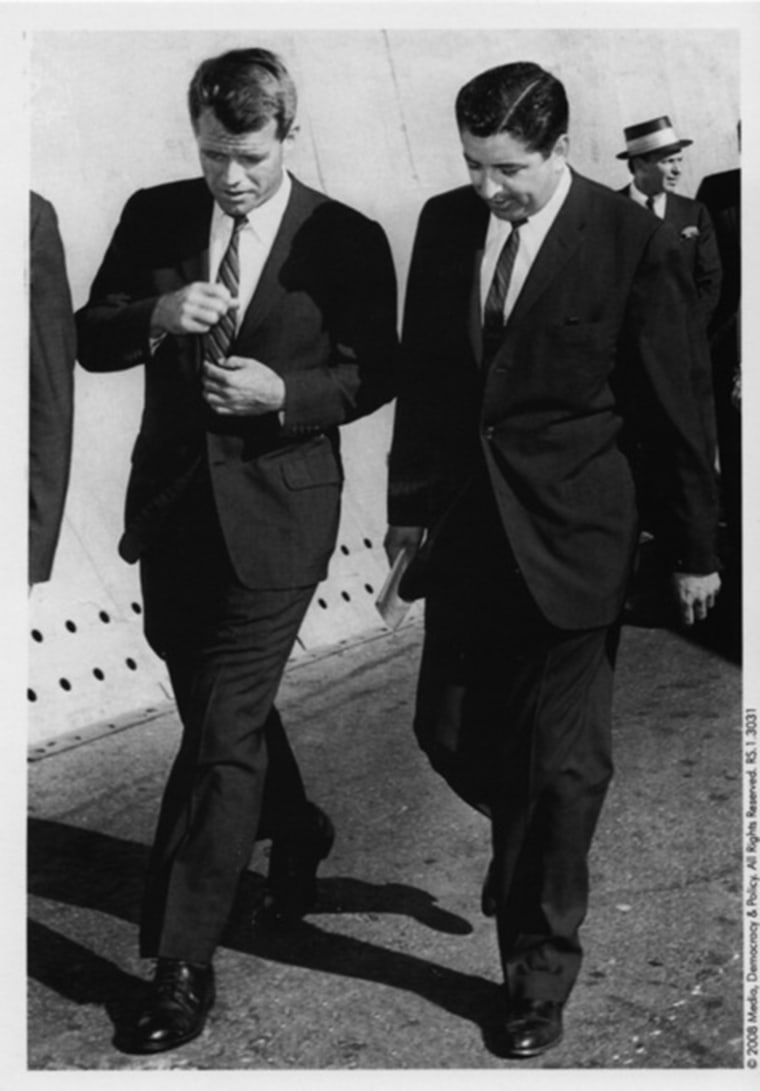

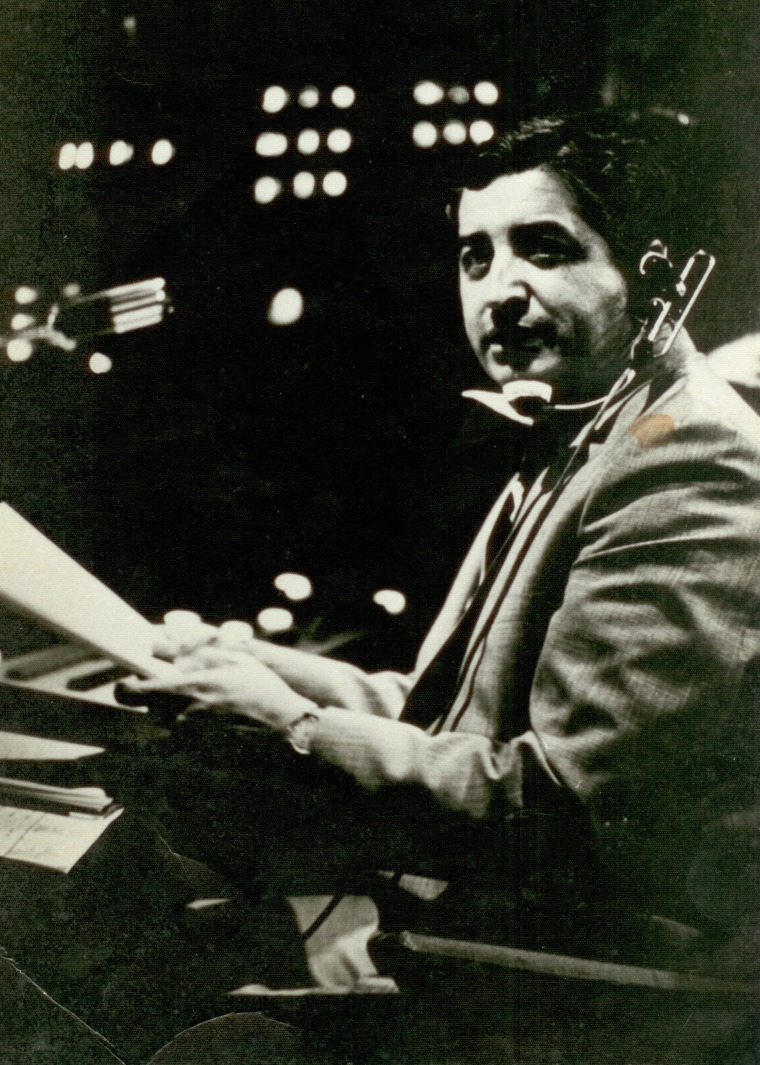

Salazar was born in Mexico in 1928 and grew up in El Paso. He arrived at the Los Angeles Times in 1959, where he was one of only a few Latino reporters. In the late 1960s, as the Mexican American civil rights movement was developing, Salazar became news director at a Spanish-language television station, while continuing as the first Latino columnist for the L.A. Times. He was also the newspaper's first international correspondent and foreign bureau chief. Salazar interviewed President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Robert F. Kennedy, among others.

Salazar often served as a bridge between the Mexican American and the white communities in Los Angeles. “Who is a Chicano?” he wrote in 1970, presaging many later debates over Latino identity. “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself.”

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

The circumstances surrounding Salazar’s killing have long been controversial. Before his death, he told friends that he was worried about being targeted by law enforcement. But the subsequent coroner’s inquest (a quasi-judicial proceeding) did not result in criminal charges against the sheriff’s deputy who killed him.

“The inquest was like a Band-Aid, it was a joke,” Stephanie Salazar Cook, his daughter, told NBC News in 2014. “Unfortunately, in that era of history, that kind of stuff happened and people got away with things.” A review of Salazar’s case in 2011 by the L.A. County Office of Independent Review found no evidence that Salazar had been targeted or intentionally killed.

The filmmaker Rodriguez believes that Salazar was in the wrong place at the wrong time. “The deputy who killed him may have acted lazily, or sloppily, with negligence or indifference to brown lives. But I don’t think there is reason to see a conspiracy.”

Some people feel that there has yet to be a definitive accounting of Salazar’s death. “There should’ve been an independent review, with forensic experts, and more people from the community, which could have produced more conclusive findings,” Félix Gutiérrez, professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Southern California, said.

“Imagine if a prominent Black journalist in the South covering civil rights had been killed by a sheriff’s deputy," Gutiérrez said. "There would have been an aggressive federal inquiry."

Salazar was ahead of his time, Gutiérrez said, in his coverage of race relations, immigration and police misconduct.

He was also a singular figure, Gutiérrez added, because he cared about marginalized people. “Yet, today he is known more for the way he died than how he lived.”

Challenges persist for journalists of color

This summer, as the Black Lives Matter movement swept the nation, several journalists reported being harassed or harmed by law enforcement officials as they attempted to cover the protests. In Minneapolis, CNN reporter Omar Jimenez and his crew were arrested on live television as they covered a May protest over the death of George Floyd. In Long Beach, California, reporter Adolfo Guzman-Lopez was hit in the throat by a rubber-coated bullet allegedly fired by police.

“It is pretty easy for the police to see you as a person of color first, and a journalist second,” said Samanta Helou Hernandez, a multimedia journalist and photographer based in Los Angeles. She was detained by law enforcement as she was covering a protest in June. “It was pretty scary. The first thing police do is turn you around and put the zip tie on your wrists.” Hernandez was released after a colleague on the scene vouched for her. She said the incident served as a reminder to her “that freedom of the press is very much under threat.”

Hernandez’ experience did not change the way she views the police. “It doesn’t make me biased against law enforcement; if anything, it gives me a deeper understanding of what is at stake.” As a freelancer without press credentials, she explained, it is difficult to convince law enforcement that she is a journalist.

The lack of diversity in newsrooms continues to be an issue for Latinos, as well. A 2018 study by the Pew Research Center found that newsroom employees are 77 percent white, and 61 percent male.

The lack of Latinos in newsrooms is “disheartening,” Hugo Balta, president of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, said. “Ruben Salazar is an example of the decadeslong fight for equality in newsrooms, and for equality in coverage of Hispanics/Latinos and other people of color.” News organizations that do not support diversity, he offered, are incapable of producing content that is fair, relevant and accurate.

In July, a coalition of Latino journalists at the L.A. Times penned an open letter to their management, seeking better representation and improved community coverage. "Today The Times continues to fail, in its staffing and coverage, to reflect a region where nearly one of every two residents is Latino," the letter states.

Amid such contemporary controversies, Salazar’s work from decades ago remains impactful and thought-provoking.

For Virginia Espino, a lecturer at the University of California Los Angeles, Salazar’s reporting provides a window into a moment in history. “That students can read his writing and interpret it for themselves, it brings it to life for them.”

Part of Salazar’s legacy, Espino said, is his connection to the broader struggle for civil rights. “In his writing, Salazar was speaking truth to power, and it was an act of defiance that was unusual for the times.” He amplified the Mexican American civil rights movement, she added, by providing it with a mainstream platform.

When she teaches about Salazar, Espino said that she feels inspired.

“My students are young and full of ideas as they come of age," she said. "In a sense, they are the grandchildren of Ruben Salazar — and I think that he would be very proud of their generation.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.