The image reverberated across the country and the world — the intertwined bodies of a father and his little girl, facedown in the waters of the Río Grande, who drowned trying to cross the border into the United States.

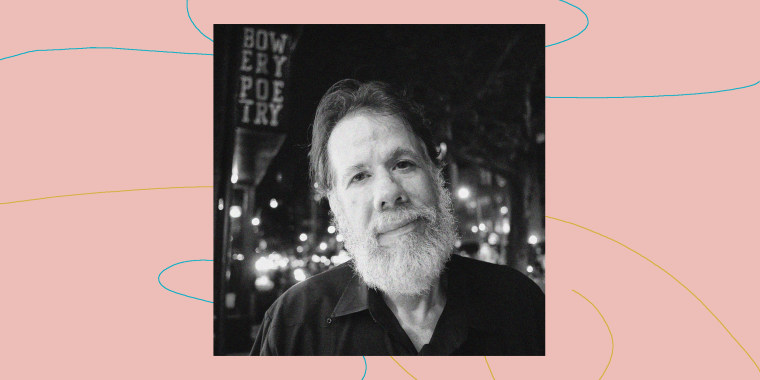

For poet Martín Espada, it was what happened after the photo came out that spurred him to write a poem that became the title of his book "Floaters: Poems," which garnered the prestigious National Book Award for poetry Wednesday.

"Can you imagine looking at that photograph and seeing a conspiracy?" he said in a phone interview from his home in Massachusetts on Thursday. After reports surfaced of a member of a Border Patrol Facebook group questioning whether the photo was "doctored" because he had "never seen floaters like this," Espada wrote a poem about Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter Valeria.

"It was a way to humanize the dehumanized, taking their name back," Espada said, "... to demand that we see these people as people. That theme runs throughout the book."

In announcing Espada's award, poet A. Van Jordan said the poems in "Floaters" "remind us of the power of observation, of seeing everything that’s in front of us, what’s behind us ... This is a collection that is vital for our times and will be vital for those in our future, trying to make sense of today."

Espada, who said he was still "stunned" about the announcement, described the award as not just a recognition of his work, but also "a recognition of all the people in my work" — those whom he gives a voice to in his poems.

"Letter to my Father," which he describes as his favorite poem in the book, came after Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico "and I was here in western Massachusetts, looking on helplessly," he said.

His father, Frank Espada, a renowned photographer and activist whose photographs are in the Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress, was born in the Puerto Rican mountain town of Utuado. The town was devastated during the hurricane and was constantly in the news.

"I saw this destruction and I began to talk to my father — my father had already been gone, dead since 2014," he said. "I was talking to his ashes in a box, wrapped in a Puerto Rican flag, and began to tell him what was happening, as if he could still hear me."

"I was telling him what was happening to Puerto Rico, to Utuado, Trump throwing paper towels," Espada said, referring to then-President Donald Trump, "and how I wished he could come back and make things right. That became the poem 'Letter to my father' — I promised that one day I would go and spread his ashes in Utuado."

A professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a Pulitzer Prize finalist for his 2006 book, "Republic of Poetry," several of Espada's poems in "Floaters" pay homage to a generation of groundbreaking Latino activists in New York City. One is a tribute to the poet, activist and former Museo del Barrio director Jack Agüeros and another to Luis Garden Acosta, an activist and former Young Lord who founded a seminal, youth-centered community health center, El Puente de Williamsburg, in Brooklyn, where Espada was born.

“They saw through the fog and clouds and saw there was something on the other side," Espada said about Agueros' and Garden Acosta's work. "Don't we need that now?"

Their lives are also a reminder of the need to connect to the lives and issues around us. "Without community, what does it mean to be a writer?" he said.

The book includes a series of love poems, "dedicated to my wife, who is a teacher and poet in her own right," Espada said. "My father’s presence, my wife's presence, are represented in every single page."

When asked how the last few years of wrenching political changes, climate events and a pandemic impacted his writing, Espada was reflective.

"I am sometimes struck speechless. You sometimes wonder if words are going to be enough," he said. "But then you write the next poem. What choice do we have? Silence is not acceptable."

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.