Andrés Cerpa's debut book of poems, "Bicycle in a Ransacked City: An Elegy," was inspired in part by his late father’s struggle with Parkinson’s disease and the toll it took on his own journey into adulthood.

Cerpa, who is of Puerto Rican descent and was raised in Staten Island, New York, is the poetry editor of the literary journal Epiphany, and the the recipient of fellowships from the McDowell Colony and Canto Mundo. His poems have appeared in or are scheduled to appear in The Kenyon Review, The Bellevue Literary Review, Ploughshares, The Rumpus and other publications.

Cerpa recently spoke to NBC News about his book; below is a condensed version of the interview.

NBC: Your book doesn’t shy away from confronting the uncomfortable realities of dealing with a parent with a debilitating affliction. How did you eventually arrive at a language that best expressed those complicated emotions?

The poet Rowan Ricardo Phillips once noted that he often asks two questions when revising a poem: “Is it beautiful and is it true?”

To articulate the complexity of the relationship I needed to fuse what is painful with beauty and remain as honest as possible — writing this way is like loving someone with a degenerative and incurable illness like Parkinson’s.

There was no possibility that my father’s condition would improve. We knew that it would inevitably take more and more away from him, and therefore I needed to concentrate on my perspective and reactions to that reality: anger, sadness, guilt and love.

Driving my father to the doctor’s office to get more bad news was far from fun, but we enjoyed each other’s company on the way. We would talk in traffic or get a nice sandwich near the hospital, and I cherish those moments despite all the pain that surrounded them.

Not only did my family care for him, but he also cared for us during those years. My memories of our time together are expansive and that is why the poems are often lush. I wanted to slow down time for the reader and for myself, so that we could see each moment in its fullness.

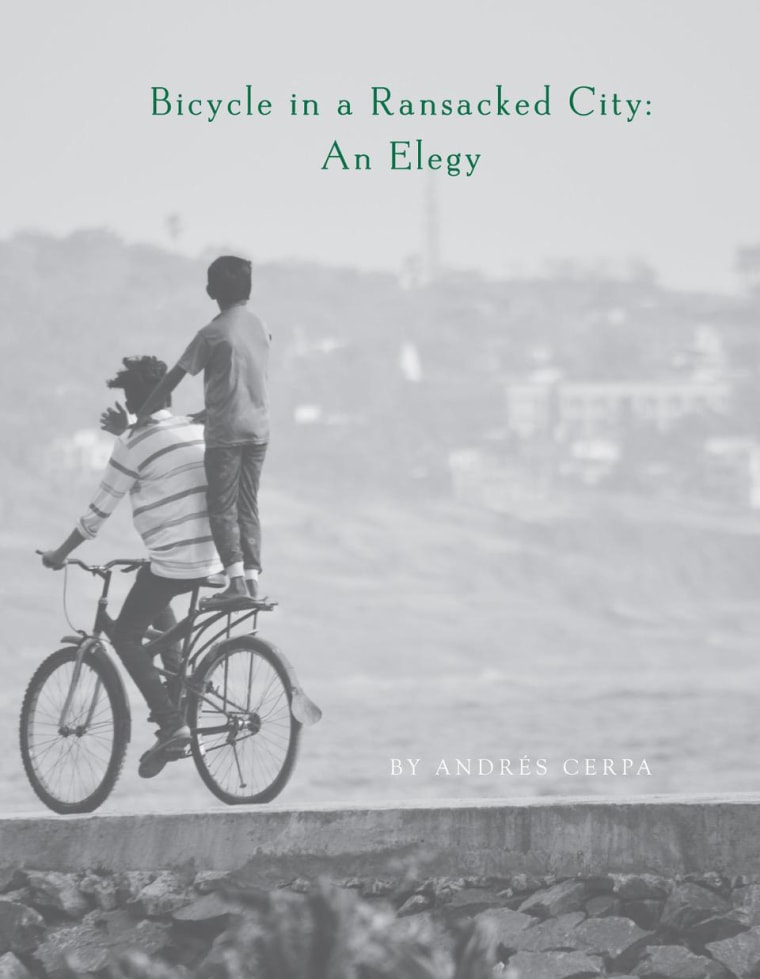

NBC: The bicycle is an important image in the book, but so are windows and doors. In your work they direct the gaze to what is possible or what cannot be reached. After writing this book, what have you come to terms with and what do you want readers to take with them?

Each member of a family must ask themselves at some point: How do I carve out a space for my own life?

I believe that it is important for all caretakers to create a nourishing space, in the broadest sense of the word, for themselves.

Sometimes that means closing a door or walking outside.

Modern medicine has allowed us to live longer and in varying states of decay. There are countless people bringing their parents and abuelas into their homes, caring for spouses, children and friends, and I hope that the book makes it to those families.

When I needed it most, poetry offered me refuge and gave me deeper access to my own humanity. My greatest hope for the book is that it will inspire and provide solace to someone in the future.

While I was writing "Bicycle in a Ransacked City," Christopher Cerrone, a wonderful composer, told me that as he got older he found that writing a piece of music that touches the light — even briefly, rather than stay inside the darkness — was the more difficult task. The doors and windows let the speaker move toward or away from that light. The challenge is to move toward it.

NBC: Even in the poems that were not explicitly about the father (like those that take place in Europe, for example), the father’s presence still looms heavily over the speaker’s experience. Why are grief and loss such powerful muses in poetry?

One reason is that they are often intimate, whether it is an intimacy we share with ourselves, what has been lost, or that we share in a collective — a family, a people, friends.

In those moments of loss, or in a period of grief, we are often pushed toward each other and pushed to look at the world anew. At a certain point, grief requires us to reassess our understanding of the world, to look back at all we’ve seen, and in that chaos attempt to find meaning.

These are also the demands of the poem. Through poetry I am given the chance to reconstruct the intensity of grief, to look back at what has been lost, and in that focus, regain some of the intimacy that has slipped away.

I felt very close to my father while I was writing this book. It helped me to connect to the totality of our lives together. Yet I also understand that I am approximating these moments as I write, but if the poem speaks some kind of truth, then it is worth the hard work of looking at the pain. It begins to be a small consolation, one small thing I can save.

NBC: "Bicycle in a Ransacked City" is fresh off the press, but you’re already committed to publishing your second book with Alice James Books. Is there anything you’d like to share about the forthcoming project?

"The Vault" will be published in June 2021 and it is both a continuation of "Bicycle in a Ransacked City: An Elegy" and a departure from it. During the everydayness of every day, we make important decisions about family and love.

In part, "The Vault" holds a journal and a collection of letters. The book asks for advice and imagines different paths. It is both deeply personal and communal.

More than ever, I want to join the reader on their path.

FOLLOW NBC LATINO ON FACEBOOK, TWITTER AND INSTAGRAM.