This week Carol’s Montes walked on stage with her parents by her side at the University of California, Davis Medical School’s graduation. The young woman with the unique first name had become “Doctor Montes.”

But she doesn't know whether she'll be able to continue her medical training to become a licensed physician. On the same day that Montes signed a contract to begin her medical residency at Contra Costa Medical Center in California, the Trump administration ended Temporary Protected Status – TPS - for Hondurans, which is how Montes and her parents have been able to live and work in the United States.

“I start residency in a few weeks. My work permit expires July 5th. I have no idea what will happen. How do I continue my medical training?” Montes said.

Montes, her parents and a sister, all originally from Honduras, have had TPS for two decades. But TPS for Hondurans ends on Jan. 5, 2020.

Montes is among nearly 61,000 Hondurans with TPS facing a possible return to their native country. In all, the administration has ended TPS for more than 400,000 people from several countries.

“To me, this decision means that the (administration) sees something inherently wrong with who we are and where we come from,” Montes said. “It doesn’t matter what we do because we are never going to be enough in the eyes of the policymakers. It is frustrating. How much can I do? How much more can I give back? How much of a good citizen can I be to prove that I am worthy of being here?”

After the U.S. granted TPS to Hondurans in 1998 for 18 months, it was continually extended by the Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama administrations, so that some families have lived legally in the U.S. for nearly 20 years.

Hondurans got the humanitarian protection after Hurricane Mitch swept through Honduras and the rest of Central America, killing thousands and causing severe damage.

Montes migrated from Honduras to the United States with her parents and older sister in 1988. She was 3 years old. They were undocumented until 1999 when they obtained TPS.

Montes was eligible to work, but she was ineligible for federal college aid because of her TPS status.

In addition to private scholarships, she paid for college and medical school by working multiple jobs while in school. Friends and people in the immigrant community also contributed to online fundraising pages that she set up year after year.

And she has returned the support.

Montes has used her medical skills to work in underserved communities, and many of her patients are immigrants, who often have little to no access to health care.

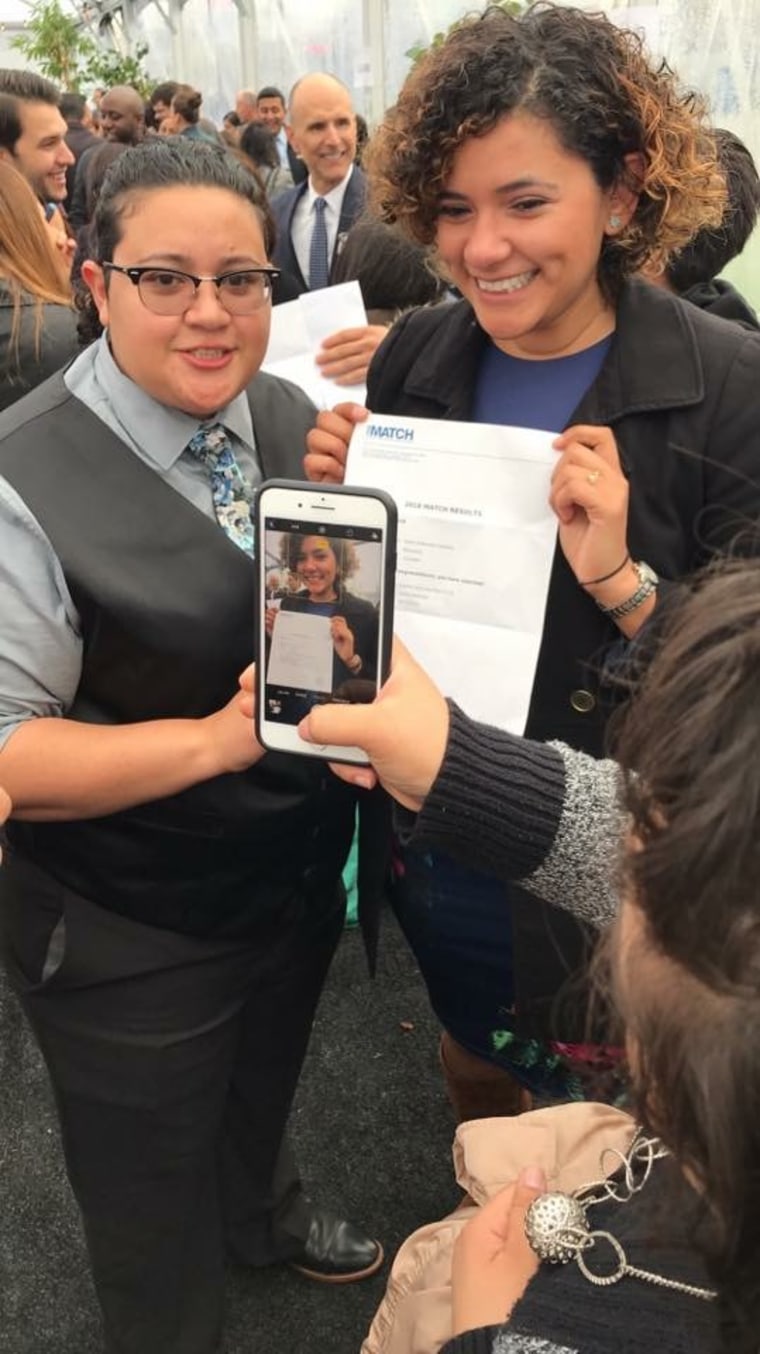

“TPS allowed me to go to college. It allowed me to go to medical school, and now that I am an official doctor, now that I have my diploma, now that I have been matched for my No. 1 choice program for (my medical) residency, I am faced with the possibility of not being able to continue my training," Montes said. "It just feels extremely disheartening."

Every 18 months Montes and her parents and sister apply for a work permit under TPS and undergo a rigorous background check. The current fee for a work permit is $495 per person, including the $85 for digital fingerprints.

“They say ‘learn to speak English,’ ‘get in the line,’ etc. … Here I am. I have done all the things that you can do. I’ve learned English. I’ve achieved the highest level of education possible — given all the limitations placed before me — and even then, we are not enough,” she said.

In an interview with NPR, White House Chief of Staff John Kelly said be believed TPS beneficiaries should be given a path to citizenship.

“I think we should fold all of the TPS people that have been here for a considerable period of time and find a way for them to be (on) a path to citizenship,” Kelly said.

Cinthia N. Flores, staff attorney at the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, (CHIRLA), said there is not a process that TPS beneficiaries can be folded into.

“There is no such avenue to adjust just by virtue of being here for a long time. There is no framework to say, yeah, I’ve been here for 15 or 20 years, let me go adjust,” Flores said. “It is based on having an immediate relative … A number of TPS beneficiaries do not have a relative that can support them with that.”

Asked to elaborate on Kelly’s statement, Helen Aguirre Ferré, a White House spokeswoman, focused on the administration’s explanation for ending TPS for Hondurans: the program was temporary and conditions in Honduras have improved.

“This is not a reflection on the Honduran community but rather a reflection on the limitations of TPS authority, which is intended to provide temporary humanitarian assistance, but is not a tool or substitute for immigration policy,” she stated.

In deciding to end TPS for Hondurans, former DHS Secretary Elaine Duke concluded that conditions had improved enough that Hondurans could return to their home country.

But the State Department is urging Americans not to visit Hondurans. In a travel warning, the department cited “widespread” violence, gang activity, human trafficking and violent crime. It warned that “local police and emergency services lack resources to respond effectively to serious crime.”

Pablo Alvarado, director of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, (NDLON), said although the clock is ticking for many people here with TPS, “even under the most desperate circumstance, people are not thinking of going back to Honduras or Haiti.”

“It is not a viable option. The assessment that people are making right now is whether fleeing from (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) is safer than fleeing from … violence in their home country,” said Alvarado, whose organization is part of a coalition advocating for TPS holders.

Suyapa Portillo, a professor at Pitzer College conducting research on Honduran migration, said returning to Honduras will be particularly dangerous for members of the LGBTQ community, which includes Montes.

“What is happening in Honduras and a lot of Central American countries is extreme violence against the LGBTQ community. They are unable to exist or get jobs. In Honduras, it is constitutionally banned for LGBT people to get married, to adopt… there aren’t identity laws in place," Portillo said.

“In the United States, we are persecuted for not being able to adjust our status. In the countries that birthed us we are persecuted for who we are,” Montes said. “It’s scary to think that we could be sent back to a country that is not our home, though we are citizens, and face marginalization from society worse than what we face as undocumented people in the U.S.”

Montes and her family have spoken to their lawyers. She plans to renew her TPS, which means undergoing an annual background and security check.

She is set to start her medical residency program at Contra Costa Medical Center in June. She plans to take a more active role in raising awareness about the challenges facing families impacted by the administration’s end of TPS.

There are few options for TPS holders to remain in the U.S. legally. They are not eligible for legal permanent residency unless they marry an American citizen or if an employer sponsors them. They can be sponsored by one of their children if the child is at least 21 years old and the child can show enough earnings to care for the parents if needed.

Montes' sister, who is 26, had to find a co-sponsor to sponsor her parents and doesn't earn enough to also sponsor Montes.

Montes faces a long wait for legal residency. A person from Honduras applying to be a legal U.S. resident and who is sponsored by a sibling currently faces a 15-year wait.

Montes is putting her hope in another option:

“We will take it day by day. I will have a valid work permit until 2020,” she said. “I hope that in that time something will change with the administration.”