Traumatic and deadly incidents in recent weeks —from Baton Rouge to Dallas— continue to highlight the fact that race and perceptions of criminality are not neutral.

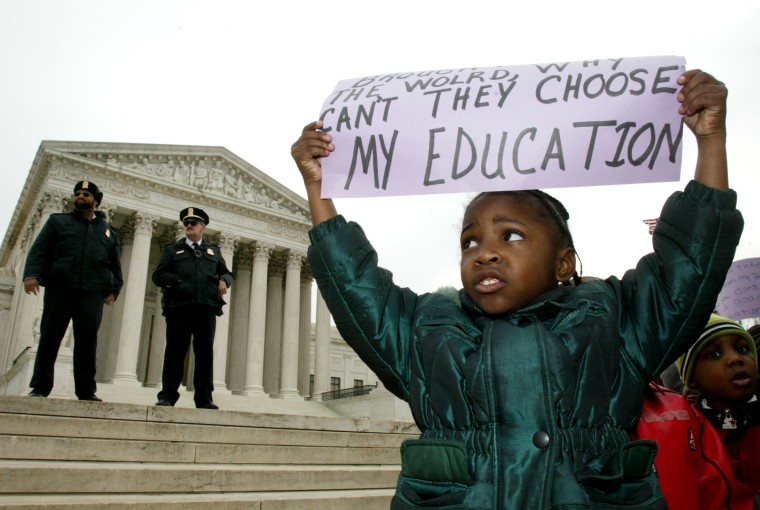

The aftermath of the tragic events in each of these communities should not be divorced from the work done to address racialized discipline practices and policies in schools. In fact, the deaths of unarmed Black people are just one part of the problem we face while strengthening our country.

Before too many Black adults are victims of police violence, become incarcerated or entrenched in the criminal justice system—too many are Black children who experience being overly- and inappropriately-disciplined in school.

RELATED: Editorial: Education is The Civil Right

The school-to-prison pipeline is rooted in over-disciplined and over-policed schools that disproportionately harm Black children and adolescents. These practices must be disrupted and supplanted to ensure that all Black children are supported as they learn and develop.

Harsh discipline practices and zero-tolerance policies that result in Black children’s suspension and expulsion from school produces compounded effects that are harmful to Black students, their communities, and our nation.

For every child that is pushed out of school, there is an increased risk of retention, school dropout, low-wage employment and poverty, or entry into the criminal justice system. Ultimately, these outcomes disadvantage America’s progress towards a stronger, united nation.

Disparities in School Discipline

For many African American children, experiencing exclusionary discipline and aggressive policing practices are not new. Excessive acts of force have been used against Black children at schools and in their communities for decades. Startling data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) underscores this point.

Beginning in pre-school, Black preschool children receive one or more out-of-school suspensions three times more than white preschool children. As students matriculate, the numbers are equally depressing. In 2013-2014, Black students represented half of the total students suspended (1.1 million). Disparities across gender and ability are also alarming. For every 1 white girl suspended or expelled, 6 Black girls are suspended or expelled.

Schools must be supportive, safe and inclusive environments for all children...

In addition to concerns of Black children being overrepresented in special education, students with disabilities are more than twice as likely to receive out-of-school suspensions. These disproportionate practices matter—they disrupt learning, lead to chronic absenteeism, and serve as barriers to graduation and can otherwise inhibit success in school and in life.

Implicit Bias, Race, and School Policies and Practices

Schools must be supportive, safe and inclusive environments for all children, especially for those who have been historically unsupported or under supported by schools and systems. African American children, despite class, geographical location, gender, or ability level, often experience school differently from their white peers—exercising differences in speech, modes for learning, dress, style and ways of being or engaging in cultural expression. These differences, when perceived by teachers and school administrators as threatening, aggressive, or disruptive, lead to school pushout.

When race is used as a predictor of behavior, Black students are disadvantaged. To guard against this practice, schools should use implicit bias research to understand and disrupt the negative impact. Implicit bias research shows how individuals, particularly law enforcement officers (or school resource officers), can make subconscious connections about Black bodies and crime. Too often Black children, especially Black boys, are perceived as older and less innocent—more threatening—than white boys.

For Black girls, the consequences of racial bias in addition to norms for gender behavior and expression further complicate how educators and law enforcement perceive and interact with Black girls. Consider for example a common double standard: when Black female students exhibit behaviors that support the success of female professionals (i.e., being assertive, demonstrating leadership skills and expressing entitlement), it has resulted in Black females being flipped out of desks, dismissed from class for “willful defiance” or otherwise pushed out of spaces where she can learn and develop.

To prevent racial biases that result in excessive acts of force or loss of life, schools must provide professional development to confront implicit biases through cultural competency, tolerance, and instituting learning opportunities to appreciate and acknowledge differences.

Law Enforcement in Schools

Zero-tolerance policies have blurred the lines between school safety, punishment, and criminality, which has resulted in an increased police presence in schools. Despite the lack of evidence supporting the use of zero-tolerance policies as effective, researchers estimate that at least 75 percent of schools have zero-tolerance policies. Chronic contact with law enforcement leads to higher rates of Black students being disciplined, referred, and arrested by school-related police.

These troubling, and often ineffective, practices and policies highlight the need for schools to rethink discipline independent of law enforcement by equipping educators with the tools needed to prevent or de-escalate crisis situations and by implementing restorative justice practices.

Rethinking the School-to-Prison Pipeline

There are no simple policy solutions to address national concerns of race, injustice, and school discipline. These challenges are complex and deeply embedded across institutions. There are no lay people in the work of supplanting negative policies and practices to support student success.

To be clear, we all have a role to play in ensuring that all students feel safe, engaged, and supported to learn. The U.S. Department of Education has launched a Rethink Discipline campaign to increase awareness of the prevalence, impact, and legal implications of suspension and expulsion. Community-led interventions, comprehensive planning and prevention, as well as the active engagement of all stakeholders must be a part of the solution.

The White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans suggests the following steps to rethink school discipline and ensure schools are safe and equitable spaces for all:

1. End Disruptive Discipline Practices

Avoid punitive school policies that criminalize youth. School leaders should limit the role of law enforcement personnel in schools. Teachers, administrators, and school staff should be equipped with the tools, professional development, and resources necessary to respond, intervene, and prevent disciplinary issues and to otherwise support environments that are welcoming, affirming and fair.

Stakeholders and advocates must also require school safety officials, including law enforcement, to be trained in cultural competence, mental health and behaviors to fairly and humanely respond to the needs of all children. Healthy and positive discipline will lead to safer and more inclusive schools and communities.

2. Develop a Response Plan

Develop and employ a range of disciplinary responses to ensure all students are able to learn in environments that are healthy, safe and supportive. Schools should utilize coaches, mentors, as well as caring and trusting adults within the community to provide support.

RELATED: How Do We Talk About Deaths of Black People with Young People?

In schools where racial and ethnic mismatch exists between students and educators, schools should work intentionally to close diversity gaps as well as provide students with diverse role models and mentors who understand cultural differences and can mitigate misunderstandings.

A successful response plan should also include positive behavioral interventions and supports as well as restorative disciplinary practices that empower students to resolve conflicts and change behaviors. These approaches should be implemented with fidelity and consistency to create a school culture of fairness and equity.

When schools implement positive disciplinary responses, students must have the opportunity to reflect, correct inappropriate behavior, and engage in activities that allow students to learn from their mistakes and to restore relationships.

3. Be Proactive, not Reactive

Schools should work with parents and families, business and industry, community and faith leaders, and law enforcement to design and implement intervention plans to prevent school pushout.

As an example, the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) suggests the following interventions: anger management; behavior intervention plan; attendance intervention plan; behavior redirection; behavior log/behavior progress report; community conference; community service; conflict resolution; diverse instructional strategies; parent observation of student; positive feedback for appropriate behavior; problem solving; rehabilitative programs; conferences; and social skills instruction.

The value and recognition of Black lives, especially Black children’s lives, requires an honest examination of racial disparities that begin with school pushout. As our country wrestles with the realities of racialized and gendered biases, it is essential to disrupt disciplinary practices that lead to disparities in exclusion, suspension, or expulsion practices.

These practices are counterproductive and do not benefit students, schools or the country. To ensure that schools are spaces for academic engagement and achievement as well as personal growth and development, an integrated and collaborative effort is required to reinforce positive behaviors, implement preventative approaches and address challenges associated with racial biases, which exacerbate prejudice and discrimination in schools and in society.

You can visit www.ed.gov/afameducation for additional information and resources to support African American youth.

Andrene Jones-Castro is a graduate intern at the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans and is a doctoral student studying education policy at the University of Texas at Austin.

David J. Johns is the executive director of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans.