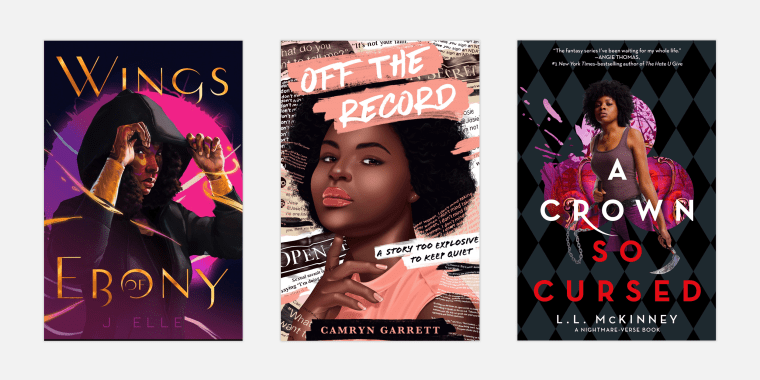

This year welcomes a slate of Black authors who will publish young adult fiction ranging in subject matter, but sharing one common goal: to expand what it means to see Black teen girls as full, whole characters.

Mahogany Browne, Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé, L.L. McKinney, J. Elle, Elise Bryant, Renée Watson and Camryn Garret are publishing books this year in which Black girls take the lead as broken and brave, warrior and wandering figures.

With a wave of coming-of-age TV shows and movies, Black girl characters often play second fiddle with little agency, low stakes and few lines. But this group of authors are among those who actively challenge mainstream notions consumers may have around what is possible for a Black girl, particularly in YA fiction. The genre lends itself to the magical, fantastical and strange, but Black girls were rarely, if ever, portrayed as witches, super heroes, goddesses or warriors.

But there now seems to be more space for YA to explore Black joy, love, fantasy, social justice and simple existence. From Black, queer and transgender representation in Kacen Callender’s "Felix Ever After," to Black fantasy like Namina Forna’s "The Gilded Ones," Black writers are taking on the mantle of portraying young Black people in a range of forms. As Black YA books continue to shift narratives and provide necessary commentary on race and respectability politics, these 2021 books spark a much-needed conversation and ignite a movement where anything is possible for a Black girl.

“Chlorine Sky” by Mahogany L. Browne (January)

Written with poetic verse, Browne’s coming-of-age novel follows Skyy, a girl struggling to move on from the end of her friendship with Lay Li. We watch Skyy as she learns to rediscover her identity outside Lay Li’s looming presence, while also trying to navigate a new romantic relationship and building her own self-esteem.

“I think we need to introduce the many ways in which Black people live and exist. We deserve to tell stories that don't just glamorize our trauma.” Browne said.

Browne wanted to write the book for “the young Black girls that are online trying to find their footing, without succumbing to toxic friendships as a means of belonging. I wanted to center a voice that we rarely consider soft or vulnerable.”

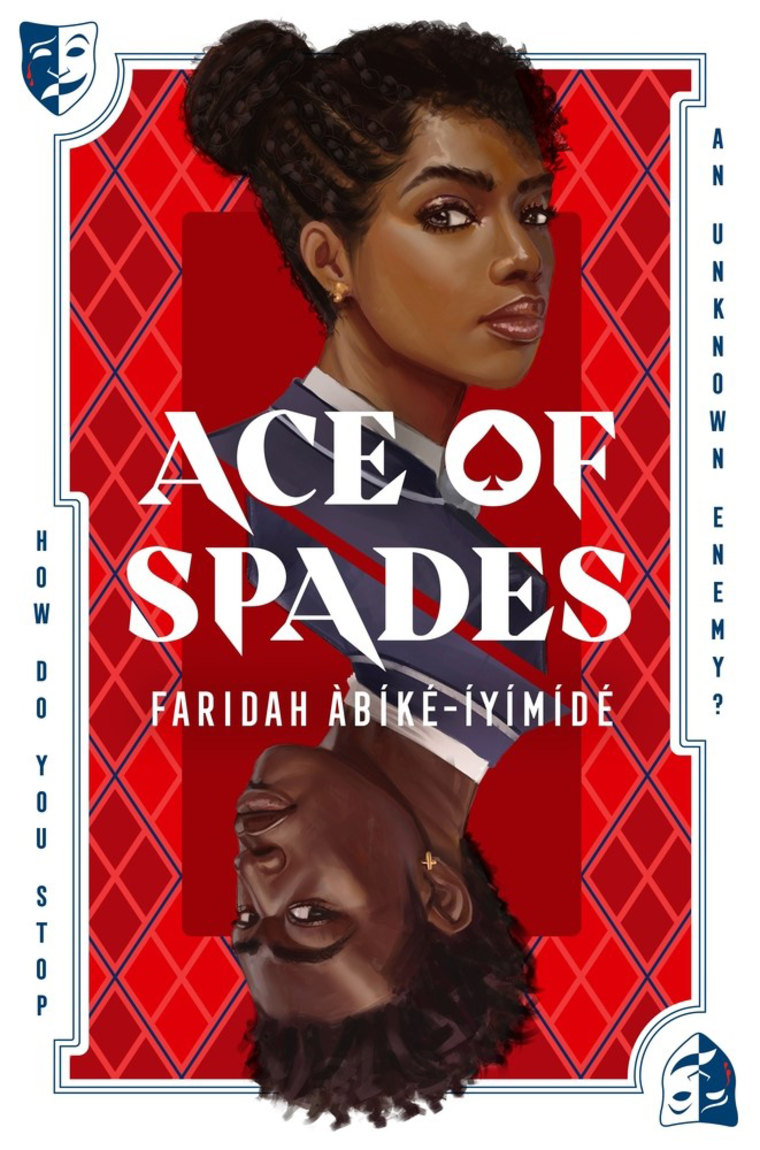

“Ace of Spades” by Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé (June)

Àbíké-Íyímídé’s thriller centers on Chiamaka and Devon, two students at Niveus Private Academy, whose pursuits of academic achievement and social status are imperiled by an online bully named Aces who exposes the girls’ most closely-guarded secrets through anonymous text messages. Chiamaka and Devon must find and stop Aces before more texts are released that place lives at risk. Àbíké-Íyímídé said she was inspired by her character in response to popular shows such as Pretty Little Liars, and Gossip Girl character Blair Waldorf. Writing a young queer Nigerian girl like Chiamaka, who is complex and flawed, disrupts the one-dimensional, heteronormative tropes of Black teens.

“I wanted to write a flawed character who is just trying to survive a world that tells her she does not have a place in it,” Àbíké-Íyímídé said. That’s why her protagonist “is ruthless in her fight to not only have a seat at the table, but to own the table itself.”

“A Crown So Cursed” by L.L. McKinney (November)

The third book in McKinney’s YA fantasy Nightmare-Verse series, “A Crown So Cursed,” continues to follow Alice as she battles a mythical army of Nightmares that have crossed over from Wonderland into her world and threaten to destroy both.

“Even though Black women are capable of great things like killing monsters, all while dealing with the nonsense of the world around them, Black women and girls also need to be protected. To be loved. To have people looking out for her even as she looks out for them,” McKinney said. “That the idea of being strong, of having to figure it all out or do it all, can in fact have negative consequences. Black women are indeed heroic, and this shouldn’t mean they can’t have someone save the day for them.”

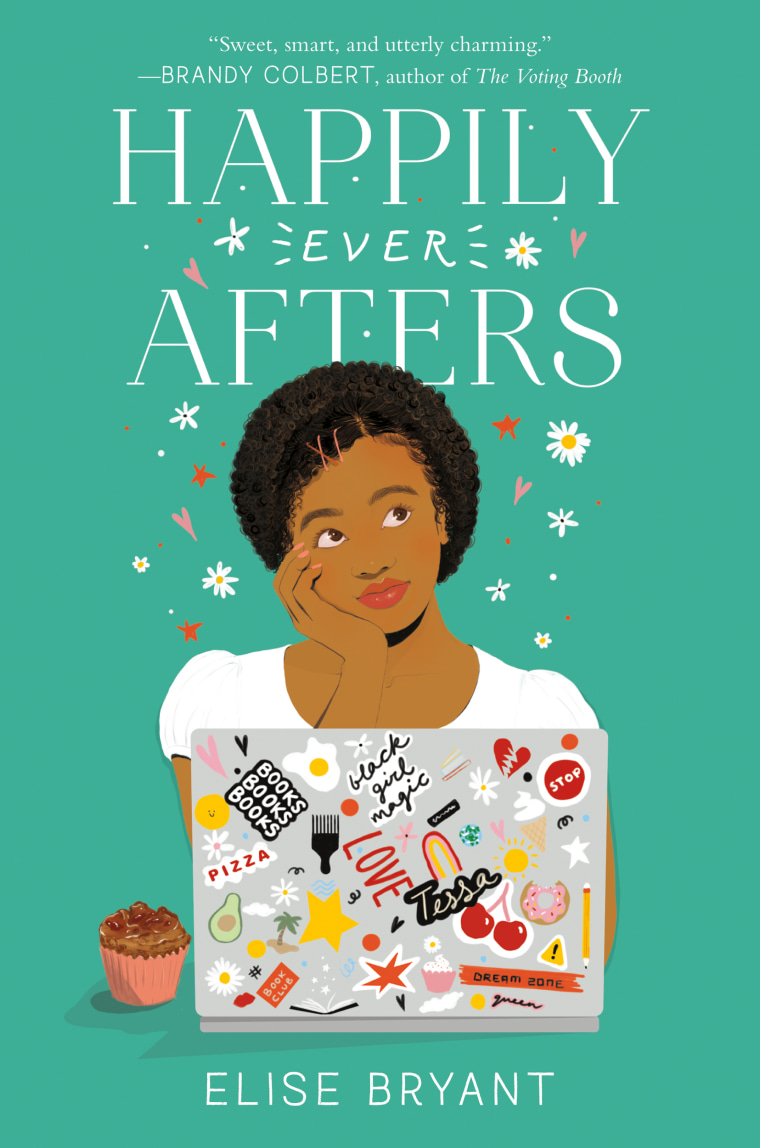

“Happily Ever After” by Elise Bryant (January)

Bryant’s debut YA fiction follows Tessa Johnson, a 16-year-old budding writer with a passion for romantic fiction. When stricken by writer’s block after enrolling in a creative writing program at a renowned art school, Tessa’s best friend Caroline comes up with a ‘happily ever after’ plan, a series of romantic novel-inspired steps, for Tessa to win over classmate Nico and inspire her writing once more. But as Tessa’s plan begins to fall in place, and her relationship with friend and neighbor Sam continues to grow, she risks losing herself and all those she cares for.

In a recent interview with Afoma Umesi on Reading Middle Grade, Bryant shared that, like Tessa, she is a romance fiction fan who has desired to see herself in the genre. “I also longed to see myself reflected in the pages of those pink-covered, swoony books I devoured. So, I wrote myself into the stories I wanted to see – mostly fan fiction and short stories.”

"Wings of Ebony" by J. Elle (January)

In a debut novel that blends YA fantasy with contemporary fiction, "Wings of Ebony" focuses on demigod Rue, a black teen from Houston who discovers her divine ancestry after a personal tragedy. Sent to the shrouded island of Ghizon to live with other godly beings, Rue discovers an evil force with the potential of consuming the world of the gods, and humans. She must summon her magic powers and embrace the fullness of her identity before everything she loves is destroyed.

Despite the fantasy elements, “Rue is me,” Elle said. “She is my sister, my homegirl, my cousin.” She said her novel is “a love letter to young girls growing up in places like where I grew up that in a nutshell says: You are magic. The world doesn’t define who you are or what you will be. Your shoulders are no stronger than anyone else’s and the world doesn’t have the right to sit on them. Know, too, that it’s OK to fall apart — to not be perfect. The world only sees your dust jacket, but I know we have to flip through the pages to even begin to touch the complexity of your richness.”

“Off the Record” by Camryn Garrett (May)

Inspired by the #MeToo movement, Garrett’s "Off the Record" reveals the power of women speaking out and standing in solidarity with one another. While writing a celebrity profile for a magazine, Josie Wright hears a secret by a young actress. As more stories arise that involve the same man, Josie faces the dilemma of whether to publicly share the secrets she has received or keep silent.

“I hope readers think about the specific ways Black women are forgotten in big conversations like those surrounding #MeToo,” Garrett said. She added that she “was really excited to write a character with anxiety because I think we see so many ideas of Black women being ‘strong’ and unbreakable that we aren't always allowed to be real people when it comes to fiction. I hope that people realize that Black women can have anxiety disorders and be shy and still be worth listening to.”

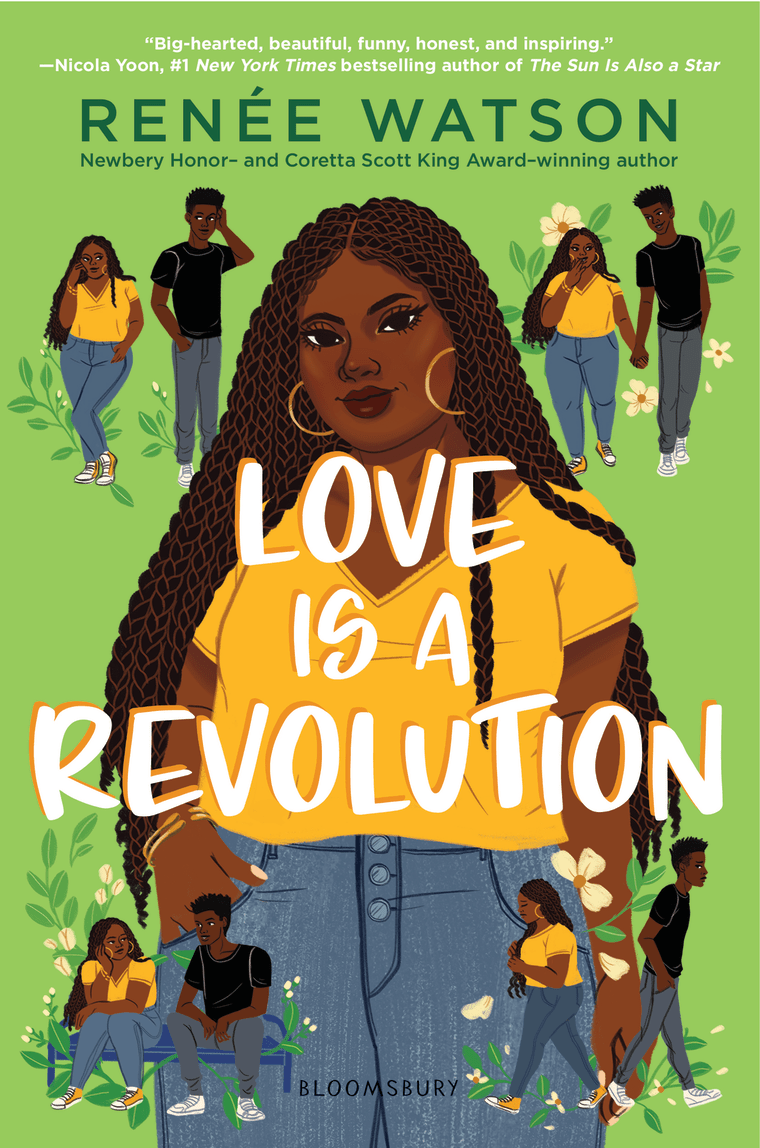

"Love Is a Revolution" by Renée Watson (February)

Watson’s “Love Is a Revolution” tells the story of Nala Robertson, 17, who is spending the summer with her family and falls hopelessly for an activist and open mic emcee, Tye. The only problem: Nala has created a false image of activism and neo-soul “wokeness” to impress him. The story shows what happens when Nala becomes trapped by a web of lies and disingenuous falsehoods. Love is a Revolution follows an everyday girl struggling down a journey of radical self-love and self-acceptance. The true revolution is in learning to show up fully and authentically.

“I wanted Nala to represent a fuller depiction of the Black girls I know, someone who is confident and not trying to change her body,” Watson said. “I wanted Nala to exist without having to save anyone — a burden we often put on Black girls and women. Nala saves herself. And in saving herself, she is able to develop healthy, honest relationships with the people in her life.”

Follow NBCBLK on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

CORRECTION (Feb. 19, 12:11 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated the age of the protagonist in "Love Is a Revolution." Nala is 17, not 13.

CORRECTION, Feb. 21 (1:50 p.m. p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article misstated the plot details for the novel "Happily Ever After" by Elise Bryant.