The literary world of the 2010s delivered a number of noteworthy memoirs by African American authors.

They include the firsthand accounts and coming-of-age recollections both of their authors and the people they lived with and among. Often, these stories emphasize the strength many families espoused as the long-felt impact of The Great Migration and the Civil Rights Movement enveloped them and the communities around them.

For author Morgan Jerkins, memoirs are also the perfect vehicle to tell often hidden stories of the black experience. Jerkins, author of the 2018 New York Times bestseller “This Will Be My Undoing,” partly attributes this rise in published memoirs to an increase in personal stories many people — particularly young women — have been sharing online.

“Luckily I was a part of that wave,” Jerkins told NBC News. “The truth is, though, we've always had our personal stories to tell. I think we're all generally nosy people to various degrees but now there's a profitable market from it, and you have to move with those waves, you know?”

Jerkins — currently the senior editor at Medium’s ZORA magazine, explored her own relationship to feminism and pop culture in her first book. Jerkins’ next memoir “Wandering in Strange Lands” (due out in 2020) will focus on her family’s experiences during The Great Migration. Jerkins said she was motivated to do so after realizing there was much she didn’t know about her family's experiences — and challenges — in the South.

“I wanted to slightly shift the lens away from my personal life solely and investigate more of the secrets and broken pieces of my families' histories which had been ‘lost’ or just not talked about since they moved away from the South,” she said.

Jerkins is not alone in using her writing as a way to tell family stories in a deeper and more personal way. As the decade comes to a close, we’re looking back at notable memoirs from black authors.

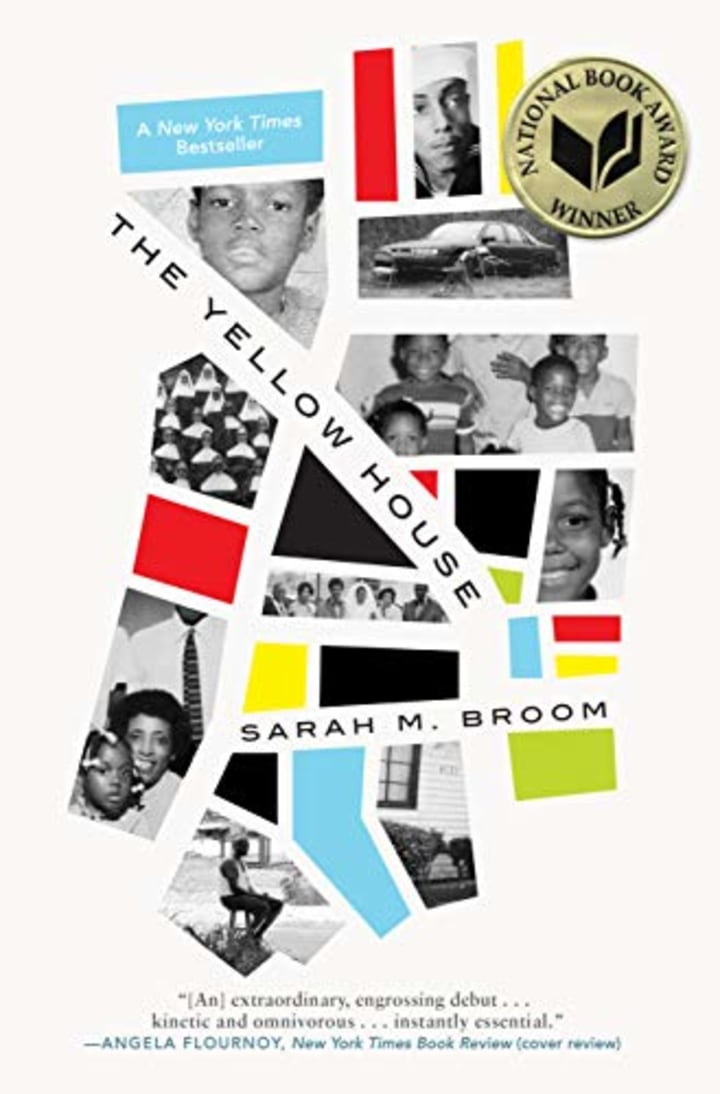

1. “The Yellow House” by Sarah M. Bloom

Author Sarah M. Bloom titled her memoir after the small New Orleans shotgun house her mother Ivory Mae bought in 1961. The house was situated in then up-and-coming New Orleans East, home to a NASA plant — the neighborhood was deeply invested in science and the space race throughout the sixties. A widow, Ivory Mae would later marry the author’s father Simon Broom and raise her blended family (which would eventually number 12 children) between the yellow house’s walls.

Everything changes for the family when Simon dies just a few months before Bloom’s birth. Through the lens of the house, Bloom navigates 100 years of her family’s history, while also examining how the yellow house’s legacy endured even after Hurricane Katrina wiped it off of the map.

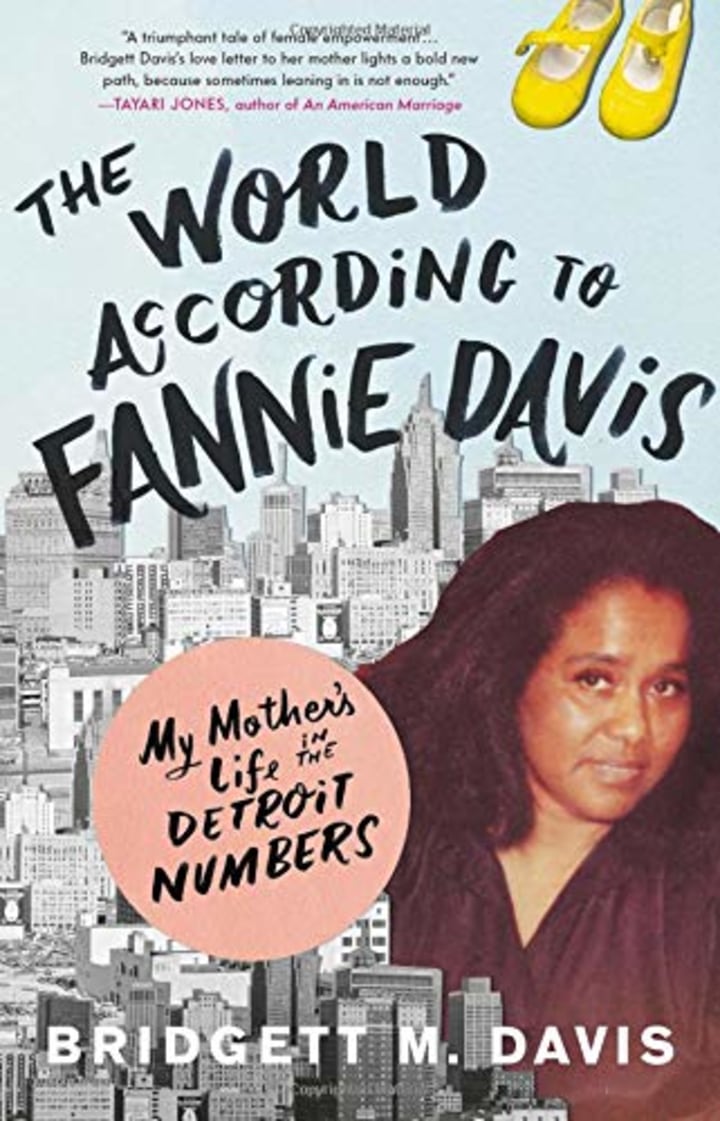

2. “The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother's Life in the Detroit Numbers” by Bridgett M. Davis

Growing up in Detroit in the 1960s, Bridgett Davis always felt she had a secret. Her mother Fannie was a numbers runner which meant that, as Davis puts it, “Mama gave us an unapologetically good life by taking others’ bets on three-digit numbers, collecting their money when they didn’t win, paying their hits when they did, and profiting from the difference.”

My mother’s message to black and white folks alike was clear: It’s nobody’s business what I do for my children, nor how I manage to do it.

Bridgett Davis

Over the course of her 30-year career, Fannie Davis thrived at her job. Those Proceeds allowed her to buy Bridgett and her siblings designer clothes and shoes and support the entire family while her husband was unemployed.

As Davis details her mother’s secret life, readers will find pockets of information about the history of lotteries in the United States and an examination of how underground economies have fueled African American communities since colonial times. Throughout, Davis acknowledges her own career as a novelist and screenwriter would not be possible without Fannie’s hard (and illegal) work.

“We lived well thanks to Mama and her numbers,” Davis writes. “My mother’s message to black and white folks alike was clear: It’s nobody’s business what I do for my children, nor how I manage to do it.”

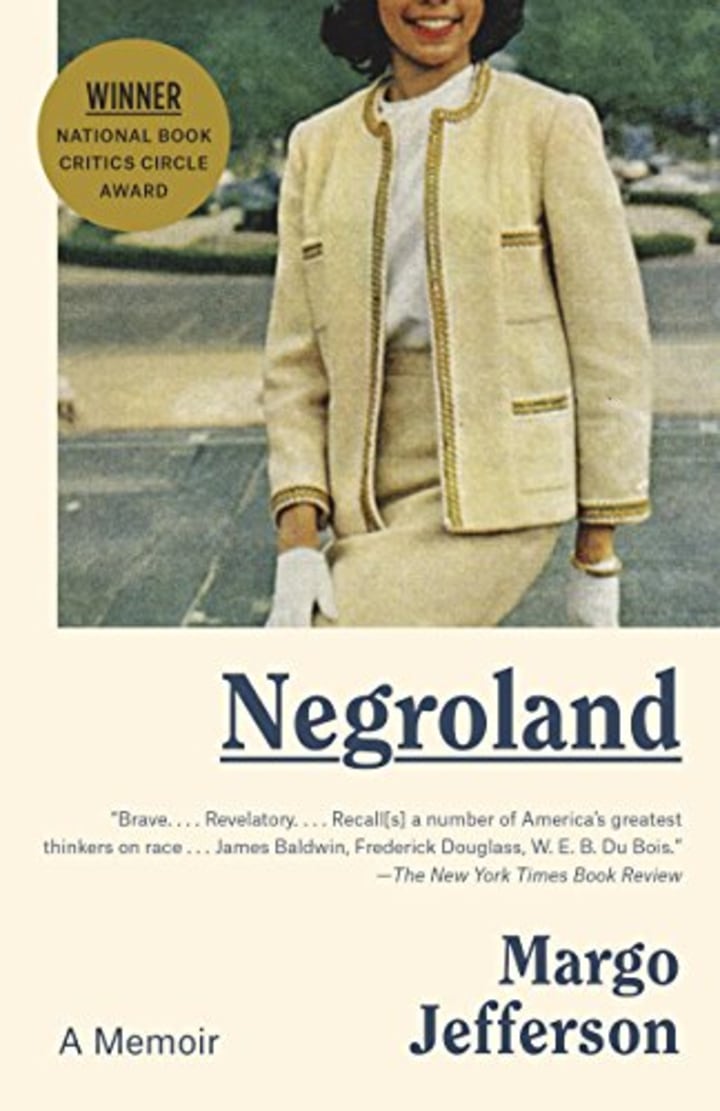

3. “Negroland: A Memoir” by Margo Jefferson

Veteran critic and Columbia University School of the Arts Professor Margo Jefferson explores the upper class Black Chicago of her childhood in this evocative memoir from 2016.

Born in 1947 to a prominent local pediatrician and his elegant socialite wife, Jefferson defines the term “Negroland” not as an exact space but as a societal position and state of mind that many upper crust families held for generations. While she acknowledges contemporary readers might have strong emotional reactions to the word “Negro,” Jefferson makes clear she is particularly comfortable with it because she “lived with its meaning and intimation for so long.”

As she dives into her experiences as an African American child of the 1950s, Jefferson gives readers a peek into a world of exclusive social clubs and parties — a society that often flourished despite segregation. Throughout, the author links her family’s story to American history, and how economic class and education can never erase racism in the United States.

4. “Fire Shut Up in My Bones: A Memoir” by Charles M. Blow

In the years since its publication, Charles Blow’s 2014 coming-of-age memoir “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” has been adapted into an acclaimed opera. Written by the longtime New York Times columnist, the book begins with 20-something Blow racing down a road with a gun at-hand, determined to kill someone.

Blow then transports readers back to his childhood in segregated Gibsland, La., a community that kept its construct virtually throughout the entire Civil Rights Movement. It was there that Blow grew up as the youngest of five sons in a family that was both turbulent and loving.

After an older cousin molested the young Blow under the pretext of playing a “game,” his childhood is thrown into further confusion. Processing his pain and navigating a world that sometimes seems filled with dangerous people, Blow eventually learns how to control his rage and, as an adult, discovers how to identify his bisexuality.

"I had spent my whole life trying to fit in, but it would take the rest of my life to realize that some men are just meant to stand out," Blow shares in one moving passage. "Whatever had shaped my identity, it was now all me.”

5. “The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South” by Michael W. Twitty

In his acclaimed 2017 memoir “The Cooking Gene,” Michael Twitty leads readers through his personal journey to find the origins of soul food.

I dare to believe all Southerners are a family. We are not merely Native, European, and African. We are Middle Eastern and South Asian and East Asian and Latin American, now.

Michael Twitty

Part food memoir and part genealogical study into both the black and white segments of the author’s ancestry, Twitty's story details the evolution and journey of African American cooking from West Africa to the antebellum South, the Civil War era and beyond. Throughout, Twitty stresses the power of the foods that enabled his ancestors to survive and how soul food — a uniquely American cuisine — can bring both white and black Americans together.

“I dare to believe all Southerners are a family,” Twitty writes. “We are not merely Native, European, and African. We are Middle Eastern and South Asian and East Asian and Latin American, now. We are a dysfunctional family, but we are family.”

Catch up on Select's in-depth coverage of personal finance, tech and tools, wellness and more, and follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter to stay up to date.