As a point guard with Wake Forest and Winthrop universities in the 1980s, Clay Dade often found it difficult to get a meal outside of the campus cafeteria. He seldom could afford to take a girl out on a date. Buying a new jacket or coat in the winter was not a reasonable consideration. Extra cash from home was nonexistent.

This was not what he expected as an athlete on a basketball scholarship. Money was, and remains, a common concern among student athletes who hail from financially challenged backgrounds.

“I come from a two-parent household, and both parents worked,” Dade said. “But we weren’t affluent. My parents never sent me money because they did not have disposable income. Thus, I never had spending money for living expenses. Ever. I really struggled.”

Dade’s story symbolizes the movement to allow NCAA student-athletes to be paid for the value of their name, image and likeness (NIL) for the first time in the college sports governing body’s 115-year existence.

The 40-member NCAA Division I Council, made up mostly of athletic directors, voted last week to suspend its rules emphasizing the importance of unpaid amateurism for college athletes while some schools have amassed fortunes off their talents. The policy shift will affect all student-athletes in all sports in all three NCAA divisions. It doesn’t affect the rules that require student-athletes to “avoid pay-for-play and improper inducements tied to choosing to attend a particular school,” the NCAA says. The policy is temporary until Congress — where there is bipartisan support for paying student athletes — puts it into law.

The NCAA’s rule change follows the Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling this month that the NCAA must provide compensation to athletes for “education-related” expenses, like paid internships and study abroad.

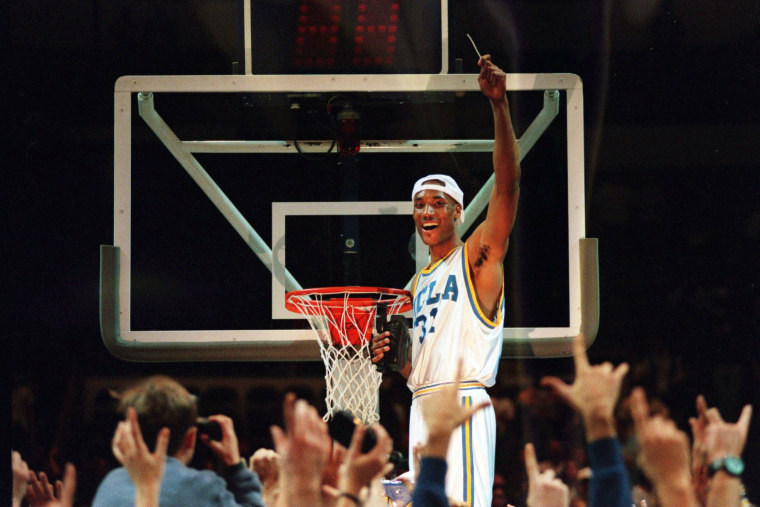

The moves cap years of legal machinations. Former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon filed a class-action suit against the NCAA in 2009, arguing that players should be compensated for the use of the names and likenesses. Also, former West Virginia running back Shawne Alston took the NCAA to court to fight restrictions on players receiving noncash compensation for academic-related purposes like internships, study abroad programs and computers.

“This is about: How do we make these athletes have a more comfortable college experience, don’t make them feel less than their college peers?” said Paul Hewitt, the former head men’s basketball coach at Siena College, Georgia Tech and George Mason University. “The NCAA has been unwilling to do something about that for decades. ... It has suppressed the earning potential for many athletes for so long.”

Hewitt said he recalled providing winter coats for players who could not afford one. “I opened my closet to players who needed something, say, for a banquet,” he said. “I’ve given a kid shoes who had holes in his shoes. It’s the right thing to do.

“But you hear about coaches committing violations and find out that he’s just trying to help a kid out. How can that be wrong?”

Dage Davis, a former defensive back for Villanova, said it is especially telling that the NCAA has been constantly reminded of the woes of the student athlete, yet refused to come up with a plan to help them.

“The NCAA has fought hard to keep not paying us in place,” Davis, 24, said. “Even though it’s wrong, for them it’s like, ‘It’s not my problem.’ They can hear all the sad stories about players, but they can’t relate to the circumstances.”

Some athletes from single-parent or low-income households receive need-based Pell Grants.

“But when that ran out, they were just as broke as me,” Dade said. “Those who weren’t college stars and getting money under the table from the coaching staff or ‘friends of the program’ or agents suffered. The rank-and-file had nothing.”

Davis witnessed teammates go without — or go to extremes just to sate their hunger. “I was fortunate that I didn’t struggle through college,” he said. “But I’ve seen so many peers struggle because there was so much that the scholarship did not cover.

“I would speak with teammates about family life; it was hard to see them struggle for even fast food. So, you saw players stealing food in the café because they were hungry and didn’t have any money to buy anything. They would literally risk it all — football, the scholarship — because they were hungry. And it should not be that way when so much money is being brought in through athletics.”

Markel Starks, a former Georgetown basketball star, found it uncomfortable to watch teammates toil, and that crystallized the need for them to be compensated.

“First and foremost, as much as people like to slam the NCAA, it gave us a platform to showcase our gifts,” he said. “So, I’m thankful for that. But at the same time, I watched a lot of my peers struggle on a consistent basis, especially monetarily.”

Playing a college sport is demanding on a student’s time. “A lot of our time is allocated to being in the gym, being in the weight room, being away from our families, not being able to do certain things other students were able to do," Starks said. "So, to see some type of relief coming the players’ way means a lot. The NCAA has made billions throughout the years off the backs of so many student athletes. So, it’s kind of bizarre that we’re at this point when so much money has been made over the years.”

“Players should be paid. Period," he said. "Inasmuch as we are student athletes, we’re athletic students. Our time is dedicated almost solely to our sport. So, if you’re dedicating that much time to your sport, and it’s bringing in revenue to the school. ... It’s an easy call. It should be an easy call.”

Hewitt laid the blame on the NCAA.

“Oh, they want the great Black athlete,” he said. “But after being around NCAA sports since 1988, the overriding feeling I have had from the NCAA is that they are trying to find ways to discourage kids from poor or disadvantaged backgrounds from showing up on their campuses.”

Betty Roby, whose son, Bradley Roby, was a star cornerback at Ohio State and now plays for the NFL's Houston Texans, sees it the same way. She said she’s relieved some compensation will come to student athletes but wonders how the pay will be equally distributed.

“It’s definitely a great thing that they will pay these athletes,” she said. “Everyone makes money off their talent except them. But it will be difficult to pay them fairly. The more popular athletes could be compensated more. So there has to be a fair compensation structure that benefits all athletes.”

That is a good problem to have, Davis said, considering the past. A wealth management specialist, he said opening up revenue streams for students had added benefits.

“If the players get paid, it teaches them about money and budgeting,” he said. “The chances of jumping to the NFL are slim. So, players would be put on a budget, which would be preparing them for life after college because they would have had some experience in it. So this is a good thing for more than one reason.”

Hewitt supposed that the Supreme Court ruling and the recommendation of the 40-member panel likely saved the NCAA, in some ways.

“But I wish the NCAA would just go away. I would scrap the whole system and put into place people who know sports and people who care about people.”

NCAA President Mark Emmert said in a statement that the NCAA was "committed to supporting NIL benefits for student-athletes. Additionally, we remain committed to working with Congress to chart a path forward, which is a point the Supreme Court expressly stated in its ruling.”

Hewitt said the changes only highlight the racial inequalities that the NCAA’s rules had long created and that had an outsize impact on Black student-athletes.

“These are the first steps in destroying the systemic rules that have always been rooted in trying to eliminate kids from poor and working-class families from competing and having access,” Hewitt said.

He cited various NCAA rules that observers for years have complained are racially biased, including Proposition 48, which made standardized test scores a key component to being accepted to universities. Hewitt honed in on the rule that football or basketball players, specifically, lose their scholarship and eligibility if they enter the draft but are not selected.

“Why can kids who play hockey and baseball go into the draft and return to college if they are not selected, but not football and basketball players?” he said. “They essentially are told that if you go into the draft to find out your economic potential, you have to give up something very valuable — your scholarship. Why would you have to give up something valuable to find out about your future? That’s craziness.”

In Hewitt’s mind, the NCAA has done little to foster opportunities for Black student-athletes, beyond the platform to play at a university.

“Name me a rule since 1984 that says to Black athletes, ‘You are welcome here, no matter where you come from.’ All they have done is put up a ‘Not Welcome’ sign,” Hewitt said. “Everything they’ve done — including the rules that govern how and the time you’re given to acquire credits in high school to qualify for a scholarship, rules that minimize prep school credits — has been proven to have a disproportionately negative impact on poorer kids, which, in this country, means Black kids.”

“Our ancestors, parents and grandparents didn’t have the opportunity to create wealth like the white community did,” Hewitt added. “They had a 200-year head start and they expect these kids who come from homes that are impoverished to do it with no fair compensation? The whole system of the NCAA has been about trying to discourage or find ways to artificially block those kids from showing up on campus."

"This Supreme Court ruling is one way, once you get on campus, to help them," Hewitt said, adding that he hoped the ruling "will lead to bigger systemic changes.”