The anxiety that engulfed Sandra McPherson surprised her. After working from home for more than a year because of the pandemic, she received an email notifying her an office-return date had been set, and, in an instant, she said she “felt tense. It was immediate. I had felt like that before — when I was about to skydive in Arizona.”

She said her parachute provided relief and even exhilaration. The prospect of returning to the office, however, did not feel as liberating.

Part of that was the comfort and convenience of working from home. There was also avoiding Los Angeles’ notorious traffic, dispensing with work attire and negotiating office politics.

“But that wasn’t what made me feel like I couldn’t breathe when I read the email,” said McPherson, who works in website development and maintenance. “It was the snide remarks, almost always about race. I loved my job, what I did, but as one of three Black people in an office of about maybe 80, there was always something from my white colleagues that made me feel uncomfortable or offended me.

“Some of it was intentional. Most of it was. A little of it was just sort of unconscious. All of it just wears on you. I was really upset.”

After a year of “not having to deal with that ... that unnecessary nonsense,” McPherson said she could not bear returning to the office. So she used the three-month notice to create her own business and quit her job.

“I should have done it long ago, when one of my white peers said to me one day, ‘So, I thought affirmative action was over. How you get here?’ He thought it was funny,” she said.

When Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election, she said she overheard a manager say, “Guess that boat to Africa gonna be full.”

“And they looked at me and snickered,” she recalled. “That kind of crap. It’s sickening. And worse, it’s tolerated by leadership. Once I learned I could do my job away from that, I couldn’t go back.”

McPherson, who is using her maiden name to avoid retaliation, is not alone in her anxiety about returning to pre-coronavirus working conditions in the office. A study by Future Forum, a research firm developed by Slack Technologies, the workplace communication company, indicated that just 3 percent of Black professional workers were accepting of going back into the office full time.

At the same time, 21 percent of white professionals look forward to a return to full-time work in the office.

“That’s because they don’t have to deal with the microaggressions we do,” said Crystal Lowe, who works in marketing and public relations in Atlanta. “And, yes, when you throw in the other elements of the last year, well, it’s really bad. Who wants to work in the office? I’d rather clean up dog poop. And I am serious.”

Those “other elements” were the contrasting images and reverberations of the Black Lives Matter-led social justice movement that took over America’s streets last summer, during the pandemic, and the Capitol riot on Jan. 6 in Washington, D.C.

After George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, Black people galvanized and raised awareness not only about police brutality, but other social ills that have long been a burden.

“And some people who were not as ‘woke’ woke up,” Lowe said. “And now they’re asking those ‘woke’ people to go into an office where they have always been marginalized? That’s a hard thing to do.”

The storming of the Capitol by Trump supporters and extremists who openly denounce racial equality elevated a long-standing concern.

“You look at those insurrectionists and most of those people look like our co-workers,” Lowe said.

Worse for Lowe, she learned her next-door neighbor of five years was among the predominantly white mob that stormed the Capitol.

“His wife told me she knew he was a Trump supporter, but she didn’t know to that degree,” Lowe said. “It was mind-blowing. That guy has been in my house. I’ve been in his. It was such a shock. But his wife left him. And I was left wondering, ‘How is it that I’m working from home and I still have to deal with this nonsense?’ It’s just too much.”

Generally, working from home has dramatically reduced the amount of discrimination and microaggressions — indirect, subtle or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalized group — many Black people say they felt in the workplace, the survey said. The need for altering their personality, or “code switching,” is minimized as well.

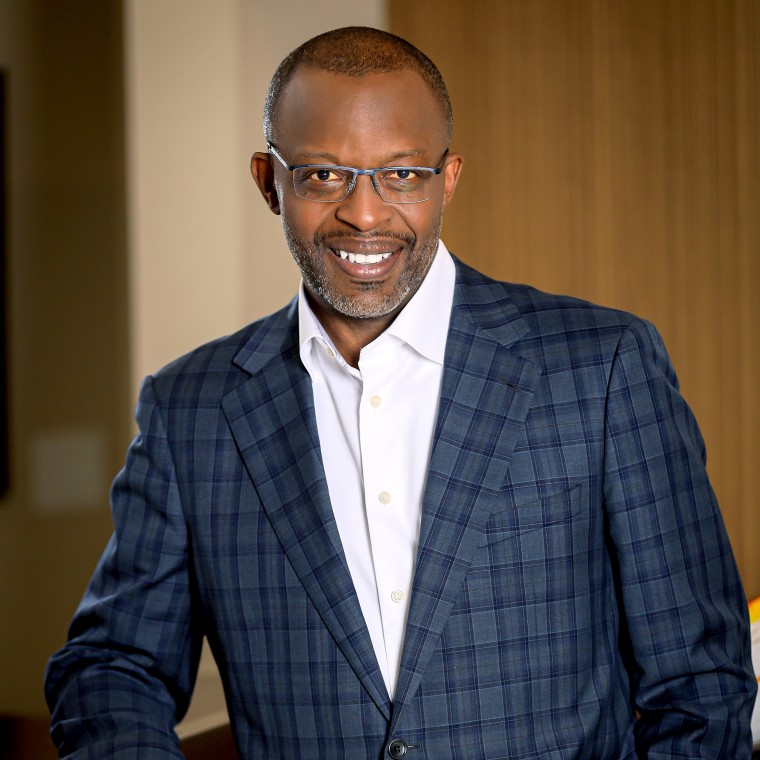

“Home became a safe space for Black workers in the last year,” said Joseph B. Hill, managing partner of JB5C, a diversity, equity and inclusion consulting firm based in Atlanta. “Their feeling is understandable: Why go into an office where I feel the impact of microaggressions that are all steeped in racism? Working from home has provided a sense of freedom from that. But what this has highlighted is that some bold and courageous conversations have to take place inside these offices to make them welcoming for Black people. It has to be intentional and it requires someone with experience coming in and leading them on this path.”

Hill added that Floyd’s killing compounded an already established discomfort in the office.

“For Black people, after seeing George Floyd saying, ‘I can’t breathe,’ as he’s being murdered and the social justice movement that followed, working in an office that feels suffocating is not welcoming,” Hill said. “And then Jan. 6 — imagine seeing a co-worker among that mob that stormed the Capitol. The office was already a high-stress place for many Black workers. Those events have heightened the stress.”

The study was revealing of the vastly different experiences at work for Blacks and whites: Only 53 percent of Black workers said they were “treated fairly at work,” while 74 percent of white workers said they felt that way. Also, 54 percent of Black workers claimed a “good or very good” sense of belonging at work, while 70 percent of white professionals did.

For Melvin J. Gravely II, the CEO of Triversity Construction in Cincinnati, the pathway to making a better office-working environment requires help from both white and Black people. In his new book, “Dear White Friend: The Realities of Race, the Power of Relationships and Our Path to Equity,” Gravely outlines some avenues to fairness.

“The first thing that white people have to do is acknowledge that there is a systemic problem with race in our country,” he said. “If their position is, ‘Hey, you’ve got a problem and I didn’t make it,’ it’ll never be solved. Also, there are some white people who want to do better, but they don’t invest the time to learn and understand, so they repeat what they know is wrong. But if they start questioning stuff, then they may get some answers to ground them. And they have to make race a thing. Talk about race when it’s only white people around and be the person to challenge stereotypical nonsense.”

It’s less complicated for Black workers, Gravely said: “It’s hard to not be messed up a little bit if you’re Black and grew up in America. Black people can’t trust their employers or co-workers right now. But Black people have to get less focused on our emotions and more focused on solutions. We are really good at articulating our pain. But we have to figure out how to rise above it emotionally.

“If your peer wants to talk about Trump and you get mad about it, I get it. But we have to figure out a way to be successful in the workplace as long as you’re in that workplace and not get so emotional you jeopardize your livelihood.”

In the meantime, being ensconced at home ranks as the preferred option.

“There are thousands of Black people who want to scream how much they’d rather work from home,” McPherson said. “But they don’t want to lose their jobs. It’s a tough place to be in. My relief from having to go into an office that doesn’t make me feel good — that actually makes me feel bad — is indescribable. I wish that for everyone. But it’s sad that most of us won’t get that peace we deserve as we do our jobs.”