Rarely do we encounter TV teachers who are representative of the educators I wish had shown up for us.

Of course, there are classic TV teachers like Jaime Escalante ("Stand and Deliver") and Joe Louis ("Lean on Me"), even Mr. Hightower and Principal Grier from "The Steve Harvey Show." But it’s Ms. Green — a Black English teacher teaching Black and Latino youth in the turbulence of 1970s Bronx — who offers a contemporary representation of the value of diverse public school educators — both teachers and school and system leaders.

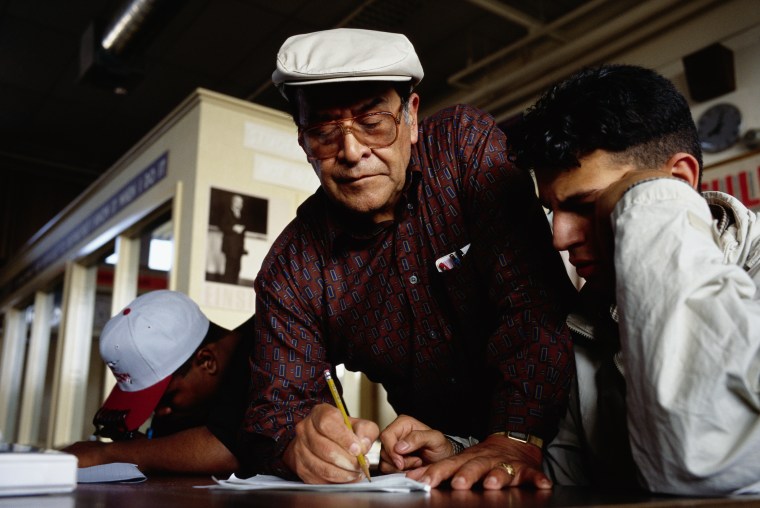

Ms. Green appears in Netflix hit series, "The Get Down," and embodies characteristics of a student-centered teacher. Ms. Green’s character demonstrates care and patience, a form of “other mothering/fathering,” that is practiced by many Black educators. Ms. Green connects learning to the realities of students’ lives and allows them to find their truths in poetry.

As a Black woman, she empathizes with her students’ home life circumstance, even making an unexpected home visit to push for academic excellence. She also appreciates how her students understand and express their culture and understandings of themselves.

Ms. Green encourages learning through hip-hop. And while viewers are never made aware of Ms. Green’s home life or experiences growing up, it is clear that she understands the social and economic hardships enveloping an entire community. Despite these challenges, Ms. Green is still able to see the bright futures awaiting her students, even if they have yet to see it for themselves.

Ms. Green is like many educators of every racial or ethnic background who teach and advocate for children and youth every day. But given the current racial mismatch in the educator labor force, many students—Black or white—never experience the unique assets that a diverse teacher like Ms. Green brings to a classroom and school environment.

To close current teacher diversity gaps, a recent report estimated that schools would need approximately 300,000 Black teachers and over 600,000 Hispanic teachers to balance the demographics between students and teachers. Scaling-up recruiting efforts and retention strategies to draw more teachers of color to the field is necessary, but must be done intentionally and across various educational institutions.

Given the imperative of diversifying the educator labor workforce, the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans, addresses three silences and omissions in the teacher diversity policy conversation.

1. Diversity is Valuable

In the past two years there have been a number of think pieces, commentaries, and research advocating for and demanding a greater commitment to teacher diversity. Achieving teacher diversity in our nation’s schools is a necessary, if not, obligatory component to improving equity in public education.

The statistics have been consistent and clear: 82 percent of public school teachers identify as white and Black males make up only 2 percent of the teaching workforce nationwide. It is also clear that racial or ethnic matching between students and teachers has meaningful effects on student achievement and the social-emotional development of African American students in schools.

Black males make up only 2 percent of the teaching workforce nationwide.

RELATED: Yale Study Finds Signs of Implicit Racial Bias Among Preschool Teachers

In a July 2016 report, “The State of Racial Diversity in the Educator Workforce,” the United States Department of Education (USDOE) stated that “diversity is inherently valuable.” While the federal government has made efforts to increase diversity in the educator labor force by offering scholarship funds, loan forgiveness, and encouraging school districts to provide recruitment bonuses, there is still much to be done.

These efforts must be accompanied by long-term solutions that go beyond initial recruitment. Research indicates that while many teachers of color enter teaching—albeit at lower rates than their white counterparts—they, nonetheless, leave the field at higher rates.

Getting teachers to the classroom is only the beginning. Schools must ensure that they support teachers of color with engaging professional development, offer fair and instructive feedback, and provide opportunities for teachers of color to teach students in ways that are authentic to their professional and personal identity. To value diversity also means that schools must change practices that breed micro or macro racial and gender aggressions. When teachers make inflammatory comments about “those” students, often times, there is a Black teacher who remembers when she, too, was one of “them.”

2. Diverse Leadership Matters

With a similar demographics as teachers, school administrators and leaders are also a racially homogenous group. The USDOE reports that in 2011-2012, the majority of public school principals were white (80 percent), while 10 percent were Black and 7 percent were Hispanic.

Because school principals have complete or partial authority in the hiring process, diverse leaders are more likely to recognize and appreciate unique strengths and teaching practices that teachers of color can bring as assets to a school environment.

For example, a Black female principal at an alternative structured high school in Texas expressed an immediate interest in one Latino teacher who, when asked why he wanted to be a teacher, shared his story about dropping out of high school and his disconnection from schooling. It takes a culturally-intuitive principal to recognize that a high school dropout, who went on to pursue a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree, can be an invaluable model of educational possibility.

Diverse school leaders can improve cultural familiarity and connections between school and minority parents and communities, particularly in linguistically diverse settings.

Beyond hiring efforts, diverse school leaders contribute to school and community relations in numerous ways. Diverse school leaders can improve cultural familiarity and connections between school and minority parents and communities, particularly in linguistically diverse settings. Diverse school leaders are more likely to negotiate or change policies and practices, such as suspension, strict dress code or surveillance practices, or teacher evaluation methods that are culturally-biased or disadvantageous to students and teachers of color.

With many teachers reporting dissatisfaction with school administration as a key reason for leaving their school or the teaching profession, we must also focus on the full spectrum of having a diverse educator labor force.

3. Achieving Diversity, without Sacrificing Quality

A common narrative that emerges in conversations about increasing diversity often suggests that increased diversity leads to decreased teacher quality and effectiveness. Without a doubt, this is false.

In fact, the challenges that are present in many high minority, high poverty schools are consequences of inequitable resources, complex and challenging socio-economic histories, and community divestment. To blame teachers, and often teachers of color, rather than working with them to address failure in high poverty, high minority schools is just wrong.

What is the logic of increasing diversity—and in this case gender diversity—without changing institutional and schooling practices that lead Black boys to underachievement?

Similarly, the failure of Black boys in our school system is not the responsibility of Black male teachers or the Black community alone. Yes, the field needs more male teachers of color, but not at the expense of maintaining or reinforcing sexism and patriarchy.

What is the logic of increasing diversity—and in this case gender diversity—without changing institutional and schooling practices that lead Black boys to underachievement? And while there are useful programs and diversity initiatives that consider the importance of both race and gender in teacher recruitment and retention, these programs must be willing to self-interrogate.

RELATED: Study: White Teachers More Likely to Doubt Prospects of Black Students

Programs and institutions must carefully analyze a history of gender discrepancies within the teaching profession as well as disrupt notions of how Black boys and men are expected to perform masculinity. Ultimately, programs, practice and policy must support Black boys and Black girls and our Black babies who do not fit comfortably within either of these socially constructed categories by calling out forms of gender discrimination in schools, at home and in our communities.

Reforming educational systems to reflect greater diversity requires a fundamental change in the structural features of how diverse teachers first experience their own educational experiences. While there is no one solution to improving the complex challenges of the educator workforce, it is the Initiative’s hope that a strategy for educator diversity will include thoughtful practices in early teacher recruitment, teacher education and professional development, and equitable teacher hiring.

Andrene Jones-Castro is a former intern at the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans and is a doctoral student studying education policy at the University of Texas at Austin.

David J. Johns is the executive director of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans.