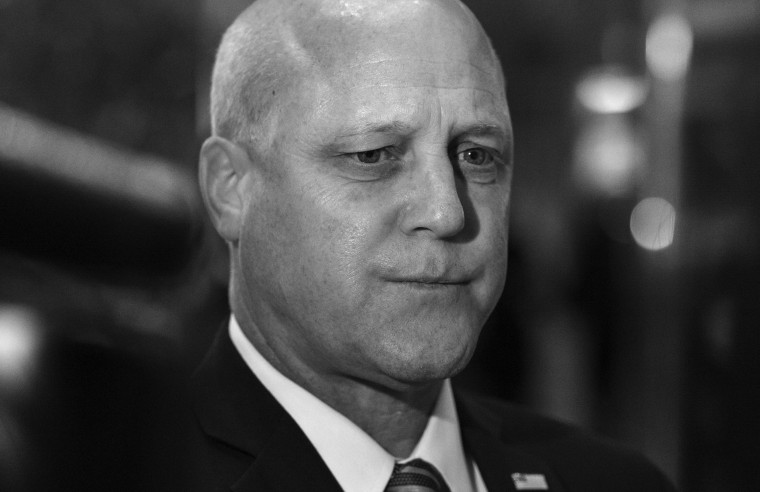

Mitch Landrieu catapulted from progressive philanthropy darling to household name when he ordered the removal of four Confederate monuments in New Orleans while serving as mayor in 2017.

Now, he’s organizing public conversations about race and opportunity while creating a program to help produce elected officials willing to prod their communities toward equity. And on Tuesday, Landrieu will testify remotely at a hearing of the House Natural Resources subcommittee on national parks, forests and public lands about his belief that all of the nation's Confederate monuments should be removed from public land.

The hearing itself carries a weighty name: "Monumental Decisions: A Long Overdue Reckoning With Racist Symbols on Our Public Lands."

But as Landrieu establishes himself as an evangelist of equity, questions loom. Is Landrieu, who has long been supported by good-government groups and other arms of the monied liberal establishment, able to facilitate sweeping change? Or is he merely a voice of those with power seeking to adjust a few things?

"We've been headed towards this moment, this situation, for a long, long time," Landrieu said in an interview from his home in New Orleans. "We, particularly white Americans, have been putting off all but the emergency work needed to wind up anywhere else."

Truth and denial

Ask Landrieu, 59, how we got to our national crises and his answer spans centuries. It's about policy and social attitudes, he says. It's about the proliferation of inaccurate historical education and a media culture that encourages white Americans to regard systems that have produced vast racial inequality as fair.

"Just one example. Do you honestly believe that Bubba Wallace is the only Black man in America who really knows how to drive fast?" Landrieu said, referring to the NASCAR driver in the news recently for supporting his sport’s effort to ban the Confederate flag. "But instead of saying to ourselves what might be wrong with a system that has only produced one top-level Black competitive driver, the vast majority of white Americans assume one of two things: Wallace is special, exceptional, or African Americans are not trying hard enough."

Some white Americans are ill-informed or in a state of denial, Landrieu said. More wrestle to embrace the comforting fiction that in America, everyone has access to opportunity if they work hard or have the right connections, despite growing economic difficulties.

"I do not mean to imply every white American is racist," Landrieu said. "They aren't. But far too many of us have, in our minds, defined racism as whether you have done anything to physically harm a person because of their race or called them a nasty word."

More Americans may better understand the racial dynamics of policing now, but they need help grappling with residential covenants, redlining, housing and mortgage discrimination and the role of each in the nation's widening racial wealth gap, Landrieu said. School funding formulas and housing patterns have left schools segregated and unequal. Systemic racism also creates disparities in the environmental conditions of Black and brown neighborhoods.

And the coronavirus' toll on Blacks, Latinos and Native Americans reflects who is hired for high-risk work (as opposed to the C-suite) and who lives in conditions that help disease spread, he said. Many white Americans need help understanding the systems maintaining inequality, Landrieu said.

"There are days when I think, my God, it is going to take a long time," Landrieu said. "But sometimes there are cataclysmic events — we are dealing with two of them now — that can make the country go, 'Wow. That's what you are talking about.' Sometimes when something is so shocking, the public's mind is pried open and then is able to go to a new place. We saw this after Katrina," the hurricane that killed more than 1,500 people in Louisiana in 2005.

Crisis energy is, to Landrieu, the best explanation for the sudden attention paid to Confederate icons. Mississippi lawmakers voted last month to remove Confederate elements from their state flag. Confederate statues in multiple cities have been toppled or removed. And President Donald Trump has made defending the statues a priority.

Landrieu has heard from the defenders of Confederate monuments often enough to anticipate their arguments. The removals, Landrieu said, do not erase history. That is impossible. The takedowns and pulldowns are understandable expressions of frustration with symbols of white supremacy.

They cannot stand, he said, urging governments to take action and predicting protests and unrest around the statues if they do not. The country is lionizing men who killed Americans to maintain slavery, he said. And for those who bemoan applying today's values to the past, Landrieu points to 18th and 19th century abolitionists. Then there's the slippery slope argument.

"People who defend these things worry: Where will it end?" Landrieu said. "My response to that is, I don't know, but I do know it should begin with these men."

Political courage and expediency

That's a position Landrieu said he was all but raised to take. Landrieu's father, Maurice Edwin "Moon" Landrieu, who was secretary of housing and urban development in the administration of President Jimmy Carter, and mentors from the Catholic Jesuit order imparted the value of political and moral courage.

As mayor of New Orleans in the 1970s, Moon Landrieu opened the full range of public jobs to all of New Orleans' residents, regardless of race. That was so controversial that a teenage Mitch Landrieu needed a bodyguard, and father and son sometimes traded dark stories about foiled threats. Today, the younger Landrieu emphatically describes Martin Luther King Jr.'s admonition for white moderates, an often overlooked part of the King oeuvre, as a prescription anti-racists need right now.

But Landrieu also worries that the growing "defund the police" conversation requires too much explanation, an indication that it will not score well politically, he said. Legitimate conversations need to be had about public funds and police reforms, Landrieu said. Investments in children and families, community development, job training and social services also create safe, healthy communities. And it is painful for a mayor to take office, as he did, and discover that 50 percent to 60 percent of the city's budget is dedicated to policing, he said.

"That is just upside down for our country and it is not working," Landrieu wrote in a follow-up email. "Law enforcement alone will not make us safer."

That is the kind of no-but-yes position that worries activists like Scott Roberts, senior director of criminal justice campaigns at Color of Change, a civil rights organization that has worked to reform bail systems and elect progressive prosecutors.

"This is really disappointing, but at the same time, this is a typical reaction for middle-of-the-road Democrats, which is where I think Mitch ran," Roberts said. "It would be hilarious to see someone doing those kinds of mental gymnastics if the consequences weren't so terrible in Black communities."

A very American reality

When Landrieu became mayor in 2010, New Orleans was a city with the usual problems, in addition to the myriad that remained five years after Hurricane Katrina.

Policing, jail, housing and infrastructure needs remained intense. Landrieu gained recognition in progressive circles and material support from multiple foundations for delaying rookie police hires, balancing the budget and insisting on a goal of awarding 35 percent of city contracts to businesses owned by women or people of color, a goal he exceeded.

He changed the bail system, cutting what was then the nation's largest jail population by more than half. And he expanded job creation efforts. Black male unemployment fell to about 43 percent in 2016. But with numbers that high, the scourge of violent crime remained.

Still, it was the statue removals that brought national attention. Some of what followed was difficult or, at least, complex.

Wealthy white people and elected officials warned Landrieu that they were prepared to make his life difficult. By the end of his tenure as mayor, every member of Landrieu's family needed a security detail.

Among other indicators of how much the removals vexed others, a rumor circulated that Landrieu was secretly Black.

"To suggest you can care about the rights and plight of Black Americans only if you are Black or have Black blood is insidious," Landrieu said. "And it is rooted in racism. The question says more about the people asking it than those who would have to answer.

"The truth is I do have Black ancestry on my father's side of the family. My great, great grandmother was an African American who was enslaved in Mississippi."

Do you know what systemic racism is?

There were plaudits, too.

Landrieu was talked about as a 2020 White House contender. He wrote a New York Times bestseller. He's a political commentator for CNN. After term limits ended his tenure in the mayor's chair, Landrieu was a visiting fellow at Harvard University leading study group sessions and seminars with titles like "Politics, Potholes and Public Service." Some of the sessions helped Landrieu analyze what he had heard on his yearlong listening tour — 13 Southern states, 28 communities large and small.

Landrieu talked with or surveyed 2,600 people on race, equality and opportunity, wrapping up months before the pandemic began. The work shaped a 2019 report by Landrieu’s organization E Pluribus Unum Fund titled, "Divided by Design."

Among the things Landrieu and his 11-person team found was that when asked about the community impact of racism, more than one-quarter, 28.7 percent, focused on personal experiences with acts of racism. Just 9.8 percent mentioned the historical impact of racism.

In mid-June, Landrieu's fund, a nonprofit underwritten by the Ford Foundation and the Emerson Collective, a social justice organization, began accepting applications from municipal leaders interested not just in setting dates for statue removals, but also in changing how cities do business, fund public services and set priorities.

"Let me tell you the reason why we got out of the Depression," said Andre M. Perry, a fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank. "It was that federal policy invested in poor people — not Black people, poor people. The people who have wealth today, and by that I mean assets like homes, didn't have it then. And Black people were largely excluded. But policy that leads to direct investments in people is how you improve lives."

But does putting a white man, even one with a progressive record, in charge of yet another program challenge or affirm America's notions of who creates, who solves, who leads?

"The idea of training leadership is a good one," said economist Darrick Hamilton, the director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University. Hamilton has worked with other economists to develop a "Baby Bonds" proposal to reduce the nation's yawning racial wealth gap.

But "if we are trying to address white supremacy, it is also important that Black voices are lifted, not just for symbolism, but included in the design and function of such a program," Hamilton said. "The country can also be guided by young Black people who are doing this work and doing it well right now."

Mary Frances Berry, an activist and professor of American social thought and history at the University of Pennsylvania, has known Landrieu for decades. Berry doubts that America can fix its problems without changing habits, she said. Among them: lionizing white saviors in every story no matter how limited their roles and describing Black activists as ineffective, loudmouth agitators. Those patterns have already shaped Landrieu's rise to national prominence, she said.

"Mitch is a nice guy. His father was a nice guy. They're all good people," said Berry, a former chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. "But he took advantage of all the work that activists in New Orleans did to demand that the city remove those statues. … Mitch was forced into the position he took. Then he hijacked the credit in a systematic way, wrote a book promoting the idea that he was brave."

But to others, Landrieu may be effective in the long term in a country with a history of racial progress followed by backlash.

"I think you could easily say that Mitch is a man built for this moment," said Marc Morial, a former mayor of New Orleans who has known Landrieu since they attended the same Catholic high school. Today, Morial is president of the National Urban League, a civil rights organization that produces the State of Black America, an annual statistical analysis of Black well-being.

"He believes the things he's been saying about this country," said Morial, who is also a member of the E Pluribus Unum Fund's advisory board. "And he can say some things that somebody else can't and be heard, precisely because he is white."