Film historian and archivist Maya Cade’s exploration of tenderness in Black cinema was inspired by a look.

The 1961 film “Paris Blues” tells the story of two expatriate Black jazz musicians living in Paris, reluctant to return to the States, where they are forced to weather racism. The pair meet and fall in love with two visiting Black American tourists, who prompt them to reconsider their staunch position. In one scene, saxophonist Eddie Cook (Sidney Poitier) gives his love interest Connie Lampson (Diahann Carroll) flowers. Carroll responds with a look of giddiness, a gesture that moved Cade. “There has to be more warm embraces,” she said.

Cade, founder of the Black Film Archive, includes this tender moment from “Paris Blues” and others from 22 films in her curated program, “Try a Little Tenderness,” for the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles.

In an industry with a troubled history of racism and stereotypical narratives of Blackness, tenderness offers a window into the nuance of Black film’s past and the ways early Black film pioneers incorporated joy amid adversity.

“We cannot change the past,” Cade said, “but when we have the information to navigate the past, we can have a better relationship to it.”

“Try a Little Tenderness” is on show at the Academy Museum through Feb. 25.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

NBCBLK: What does tenderness mean to you? What is the intentionality behind the word choice of tenderness as opposed to love or affection?

MAYA CADE: I have come to say that tenderness is spent moments of affection whether familial, romantic or among confidants. Tenderness can show up as a warm embrace, a gesture of understanding, whether that’s a head nod or a glance that you get from your family when you’re across the room and they just understand. I think that can be a tender moment. Tenderness is warmth, understanding. Of course, love is a part of it, but it’s not all of it.

NBCBLK: Do you think tenderness works in direct opposition to Black pain and trauma on screen or can they exist together?

CADE: Black film, as it’s being largely discussed right now, it’s from a place of trauma. How can we look through Black film’s past, through the archives, and highlight moments of joy and affection? "Why tenderness?" This is an offering to understand Black film history in a different lens. It really is an invitation to connect with our desires, our joys, our hopes across time. When we only see Black film as trauma, we’re limiting what it can be.

NBCBLK: Many older films caricature Blackness with characters performing as violent, hypersexual, dense individuals — and more. And I imagine that some of the films in the archive, while having tender moments, they’re not completely immune to the stereotyping that has happened?

CADE: Of course.

NBCBLK: How does that complicate viewing if the larger film has, perhaps, less progressive depictions of Blackness?

CADE: Yeah. Something I think all the time is about the agency of the actors that perform these acts, right? When I watched "Gone With the Wind," I see Hattie McDaniel. I love the gestures that she puts towards Blackness. The things that she conveys on screen, that only Black people understand. The act of reclaiming our own cinematic image is a tender act. Before we could have those conversations about what the weight of representation demands, there had to be individuals who believed in their skill, their craft. That is really powerful. The goal of Black Film Archive is to re-contextualize these moments. We cannot change the past, but when we have the information to navigate the past, we can have a better relationship to it.

NBCBLK: You have a residency with the Library of Congress, studying how tenderness appears in Black film history. What questions led you to the archive? And conversely, what answers have you found or are in the process of currently discovering?

CADE: The first time I was in the archive at the library, because I go about quarterly in person to the Library of Congress, I was just kind of overwhelmed with the weight of tender images — with how much that exists. When we go through the past, we kind of assume we have all the answers or that everything has already been explored. This prompt has really told me there are more questions than answers and that’s a positive thing.

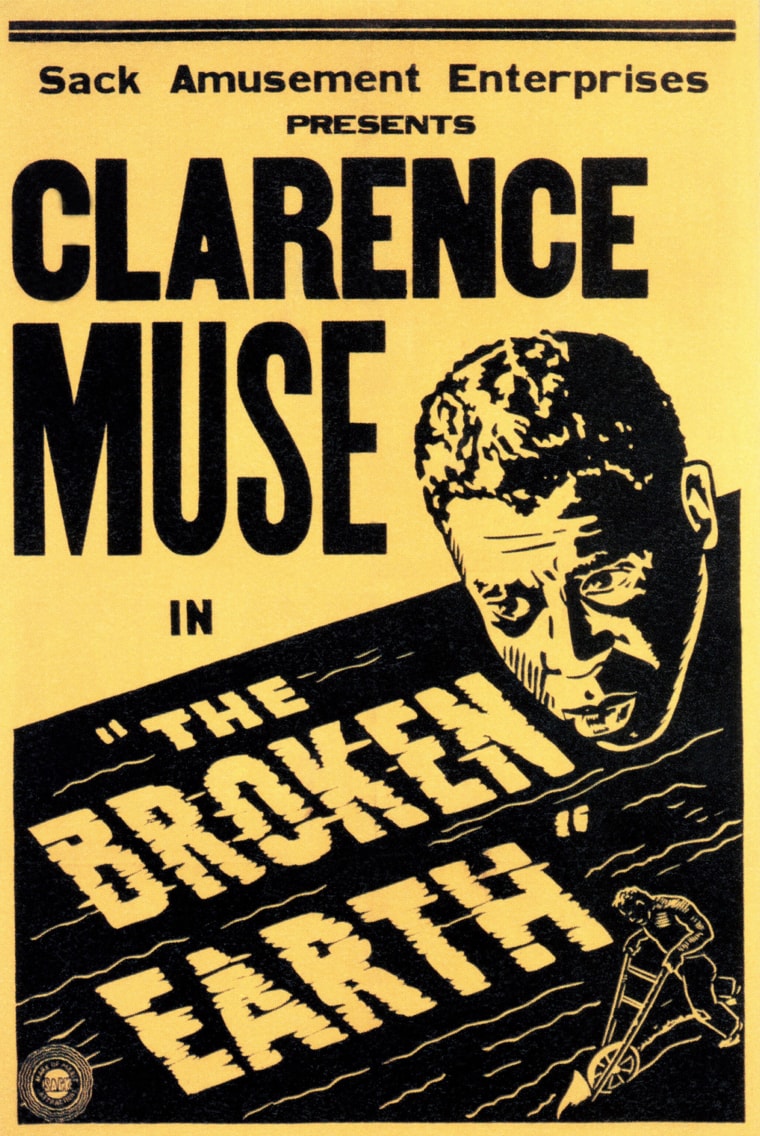

I also think about “The Broken Earth” (1939), which has a sharecropper who’s looking after his ailing son and there’s this moment where he presses his cloth on his son’s head that I just can’t get out of my head. The film is filled with Negro spirituals and this man is pleading God to save his son, and it's a very stereotypical way Black people are shown on screen at that moment. But even in that space, there are moments of warm affection and warm embrace I think we can take with us.

NBCBLK: From my assumptions, I thought maybe there would be a shortage of tenderness in Black film history because I feel like it’s not really talked about that often. So was that a surprising revelation for you? Did you think it was going to be hard to discover?

CADE: Yeah. The library gave me these basic descriptions of films. I was like "OK, let me go through this and see what comes about. What will there be? Am I only going to have 100 films in this project, a short kind of list that leans post-’50s?" And the answer’s no.

How I’m cataloging this, so you know, is that it’s pointed moments of tenderness — some pivotal plot point depends on a tender act. I will also say, the camera can be tender. As I think about Zora Neale Hurston’s anthropological films, anthropological filmmaking is usually an outsider comes into a community and is observing it to take back to, you know, other outsiders. But Zora Neale Hurston’s filmmaking is a insider coming into a community and it has such tender expressions from them because it’s almost as if the camera doesn’t exist.

There’s a lot of how the Black directors tried to showcase the realities of living. And the realities are not always a happy thing. I hope no one takes only that away from my work. Tenderness isn’t saying that there won’t be trauma. It isn’t saying that there won’t be bad times, nothing like that. But what I am saying is that tenderness is often in Black life, how we can carry through and survive those moments. The understanding that we get at home, we have to take with us into the world. My work is hoping to catalog those visions of home. All of that so that we can see those legs of hope, even if there is destruction in our path.

NBCBLK: You reference “Something Good — Negro Kiss” (1898), a picture capturing a kiss between an African American couple, in the description of the film program. One of the Black actors, Gertie Brown, was also a minstrel performer. How do you make sense of these tensions existing with this tender moment and also a fraught backdrop of the conditions Black people performed in?

CADE: To me, I think, isn’t it natural for an actor to bring their whole experience to the stage, the screen? And those complications exist in life. Why wouldn’t they be reflected in our viewing of art? Actors — their ability to perform however it was, there was a beauty in them having a showcase for skilled crafts because this film’s from 1898, one of the earliest Black films. So, yeah, those complications will exist. Especially the ways that, you know, Black films come to be. A lot of the Black films we discussed from the ’20s have white producers. I think what I come to take from the work is that it has something significant to say about the Black experience. Black film resists all convention. It resists all categorization. There are complications, you’re right. My role is only conceptualizing it so people understand what they’re viewing. It’s a proud role that I undertake.