Earl G. Graves Sr., cheerleader in chief for African American entrepreneurship, was remembered by associates and admirers as an icon who spotlighted the need for more wealth generation and business acumen in the black community.

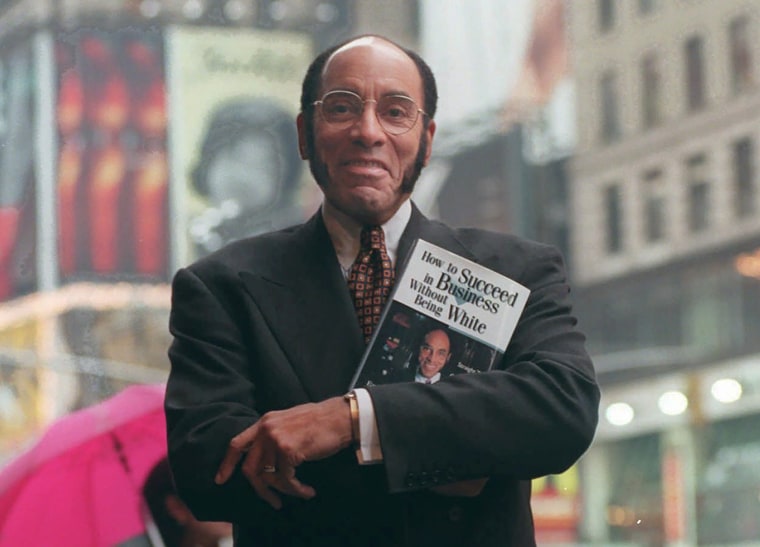

Graves, whose Black Enterprise was the first African American owned magazine to focus on black entrepreneurs, died April 6 following a battle with Alzheimer’s disease. The magazine’s founder and longtime publisher, known for his impeccable sense of style and mutton chop sideburns, was 85.

A towering figure literally and figuratively, Graves emerged from the tumultuous 1960s convinced that without a strong African American business and entrepreneurial class, real civil rights progress would remain elusive.

“He is an icon of immeasurable proportions,” Bishop T.D. Jakes, senior pastor of The Potter's House in Dallas and author of “Soar,” a book on entrepreneurship, told NBC News. “His impact in inspiring other people to be entrepreneurs, to think in a business context, to have an air of professionalism left an indelible impression on the world.

“He was a trailblazer, and whatever we become [as entrepreneurs], we will be standing in footsteps that he already walked in,” Jakes said. “He certainly set the pace. He’s a legend. We love him; we continue to love him.”

Born Jan. 9, 1935, in Brooklyn, New York, Graves had a front-row view of the political and social upheaval of the 1960s, particularly when he served as an administrative assistant to Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.

After Kennedy was assassinated in 1968, Graves began researching black capitalism. He created a newsletter that would connect businesses owned by African Americans across the nation with federal agencies that were being formed to boost business opportunities — particularly the bureau known today as the Minority Business Development Agency. That’s according to Alfred Edmond Jr., senior vice president and executive editor at large of Black Enterprise, who began working for the magazine decades ago, just shy of his 27th birthday.

Someone — Edmond isn't sure who — suggested that "Mr. G" turn the newsletter into a magazine.

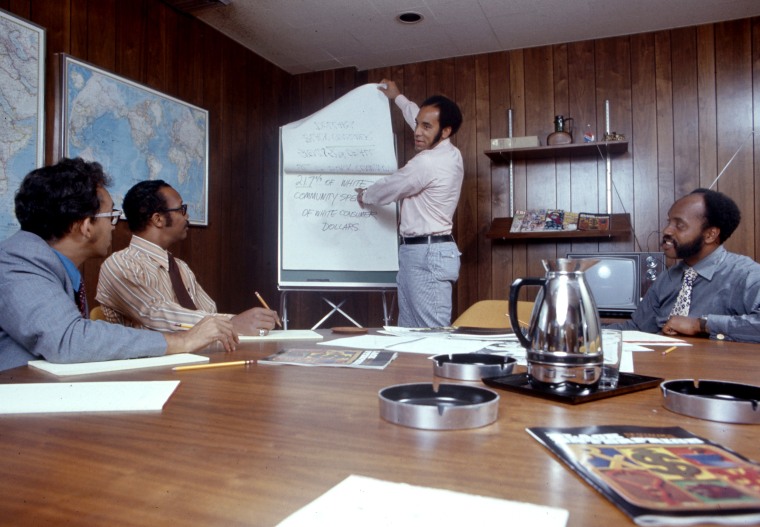

He did. Black Enterprise launched in August 1970 with a circulation aimed initially at the nation's increasing numbers of African American entrepreneurs, doctors and lawyers and later at the growing corporate class, Edmond said.

The magazine, whose circulation exceeded 500,000 in the most recent audit, eventually blossomed into a multimedia juggernaut that today gets most of its revenue from events and its website rather than the print publication.

Still, Edmond said, the overall mission never changed.

“The mission to this day is about educating and empowering African Americans to be full participants in wealth creation, in the global economy,” he said. “You're not really being successful in business unless you're helping to empower other people's success.”

The operation provided corporate America and the finance industry, which were slow to welcome African Americans, a window into the world of successful black business owners, doctors and other professionals. And it gave those aspiring to join the professional ranks a chance to see people who looked like them on the cover of a national publication.

In a statement, Robert Johnston, co-founder of Black Entertainment Television, said Black Enterprise proved vital for “every black entrepreneur and every black corporate executive who reached the pinnacles of leadership in corporate America.”

The magazine “was and still is our bible,” thanks to Graves’ leadership, said Johnson, also founder and chairman of the RLJ Companies. “Its stories of our achievement are, in chapter and verse, our religion.”

Graves’ “tireless advocacy of black businesses moved both the white and black business community to accept the fact that black enterprise deserves to stand shoulder to shoulder with American enterprise,” Johnson, who counted Graves as a friend and mentor, said.

Beyond heralding the current crop of entrepreneurs, Graves had a keen focus on nurturing the coming generation, co-workers and friends said. That included his three sons.

Earl G. “Butch” Graves Jr. serves as the president & CEO of Black Enterprise.

In 1995, a $1 million gift made Graves Sr. the largest single donor at the time to his alma mater, Morgan State University, a historically black university in Baltimore. The university is now home to the Earl G. Graves School of Business and Management.

"What Black Enterprise actually did, coming out of the '60s, was ... to address stereotypes that many held about whether African Americans could actually be successful entrepreneurs en masse,” Morgan State President David Kwabena Wilson told NBC News.

"And so here is Black Enterprise basically showing every month just tremendous faces of people who look like us. And it provided so much motivation for young people to see that and to aspire to that,” he said.

As an employer, the magazine served as a stepping stone for young African American journalists eager to write about business news.

Michelle Singletary, personal finance columnist for The Washington Post, was a preteen when she began seeing the magazine in medical and dentists’ offices and in hair salons.

“What the magazine always stood for, what Mr. Graves stood for, was self-sufficiency,” said Singletary, who freelanced for the magazine early in her career. “I grew up in a time where there were a lot of aspirations to work for major corporations because that’s where the pay was, that’s where the benefits were. But deep down … there was always this aspiration that at some point you could be your own boss.”

Black Enterprise provided a manual, a goal embodied in its original tagline, “Black America’s guide book to success.”

“There is still and will always be a need for what he put in place,” Singletary said, “which is a place where people could go and read about people who look like them.”

Karen Robinson-Jacobs is a former reporter and editor with the Los Angeles Times. She is currently based in Texas.