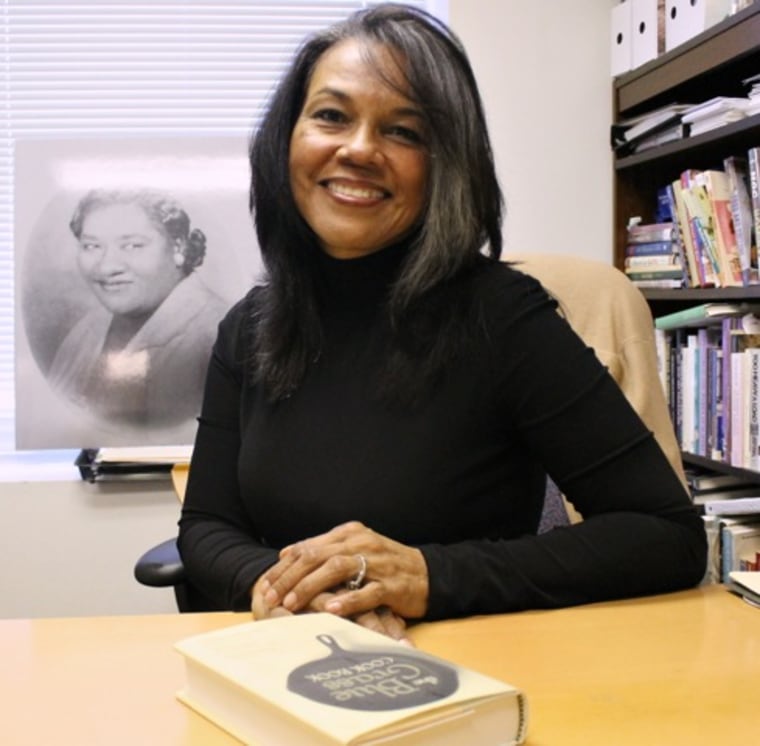

Toni Tipton-Martin was looking for her grandmother but couldn't find her anywhere.

Before becoming the food editor at the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1991, she worked as a nutrition writer for the Los Angeles Times. Part of the job was spending countless moments sorting and organizing cookbooks in a library stuffed with volumes depicting the food of distant places — like the Austrian Empire — but barely covered African American cuisine.

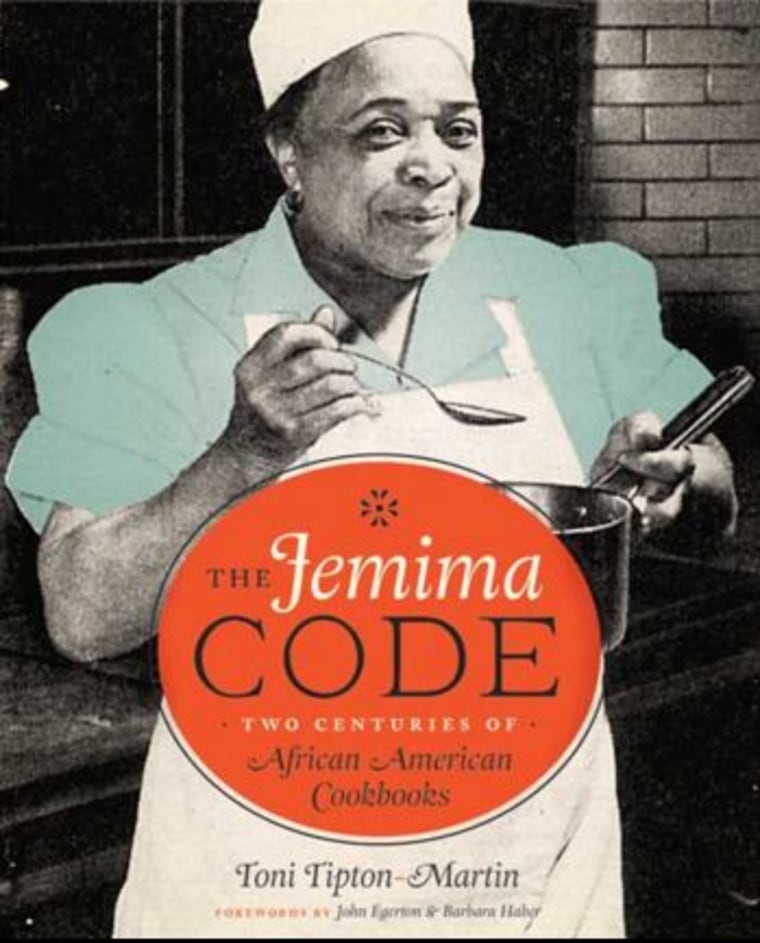

"I wondered, ‘Where are all the black cooks?’" Tipton-Martin writes in her new book, "The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks."

The little material she did come across was disparaging and stereotyped, Tipton-Martin said. Aunt Jemima, the historic symbol of the "Mammy archetype," was portrayed as a benign, subservient laborer with a proclivity toward making delicious meals. The skills necessary to create those intricate dishes —stews and meats and cakes — were assumed innate.

"When we were given acknowledgment for being talented, that was represented as some kind of natural instinct," Tipton-Martin said. "And not through daily practice and daily refinement of one's craft."

So, Tipton-Martin eventually developed a mission: dispel the myths she was finding on paper and discover the traces of culinary history left behind by women like her grandmother. She had to break the code.

"The Jemima Code" showcases about half of the three hundred rare cookbooks she spent years accumulating.

"I started seeing cookbooks as a mechanism of hearing voices in the first person," Tipton-Martin said.

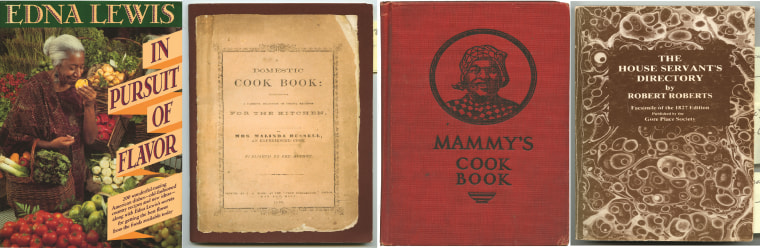

One of those voices belonged to Malinda Russell, a widow and single mother of a son with a physical disability; she once hoped to move to Liberia before thieves thwarted her plans. Russell worked as a laundress, ran a boarding house, and eventually opened a pastry shop in her home state of Tennessee. While living in Michigan, she wrote "A Domestic Cook Book: Containing Useful Receipts for the Kitchen" in an effort to raise money and get back home.

"...By hard labor and economy, [I] saved a considerable sum of money for the support of myself and my son," Russell wrote.

Russell's self-published 1866 book is the first written by a woman featured in "The Jemima Code." The cookbooks are ordered chronologically so readers can follow the social and historical arcs of the various writers' accomplishments. The oldest book in the collection is from 1827 and by Robert Roberts, a household manager for the governor's mansion in Massachusetts.

"We learn a lot about what he values, what his work ethic is, what his character is like. We learn about really the level of minutiae required for these people to perform without the ability to read or write anything down," Tipton-Martin said. "Things like how many inches the table cloth needed to be off the floor."

The recipe books span not only centuries but also nations and countries and "The Jemima Code" challenges the notion that African American cuisine is strictly soul food. Tipton-Martin knew first-hand that growing up in the black suburbs of Los Angeles meant dinnertime was not always the "traditional" southern meal.

"I'm not prepared to claim the definitely African-American core diet food… It's so complicated," Tipton-Martin continued. "We were close to Mexico, so we had a lot of Mexican seasonings and spices and enchiladas and tamales."

Ultimately, Tipton-Martin hopes to widen the understanding the public has on African-American cooks, after years of being closely defined by what they prepared at home when their "resources, tools, conditions and opportunities were severely limited." Unlike, she explained, today's celebrity chefs who are judged solely on the food made at work and not home with their families.

"These books demonstrate what they cooked when they had the ability to let their imaginations run free," Tipton-Martin said.