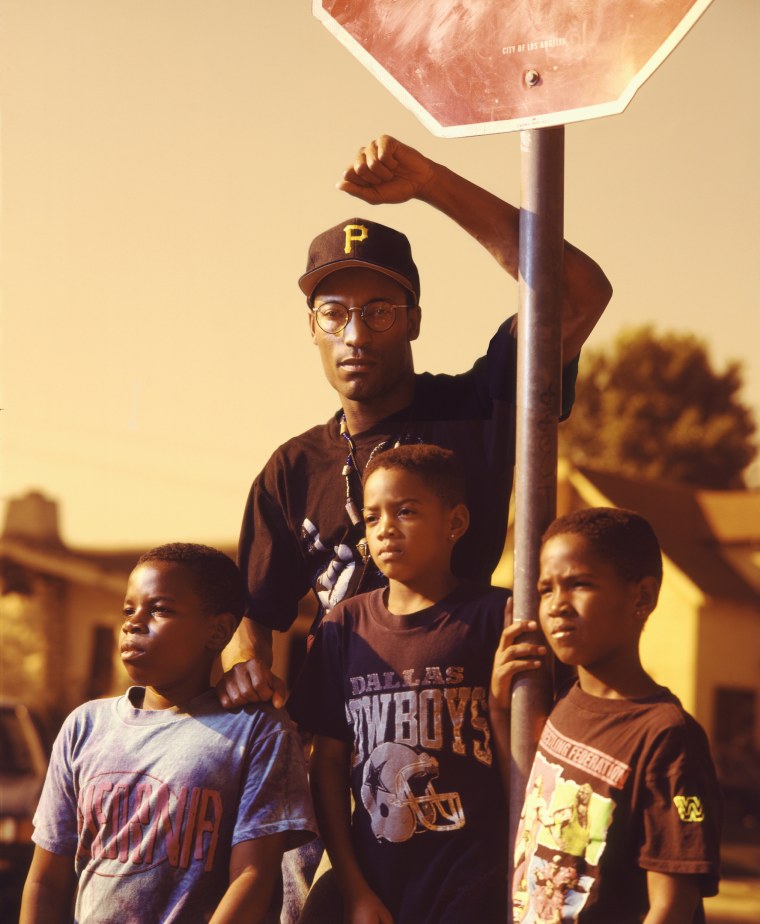

In a 1990 photo on the “Boyz n the Hood” set, director John Singleton is wearing a black hat with a simple message that embodies his legacy and impact: South Central Cinema.

Singleton, who died at 51 on Monday from complications of a stroke two weeks ago, was a masterful storyteller, with a keen eye for authentic stories about the African American experience. As a director and producer for more than 25 years, he worked with emerging talent, A-list stars and big-dollar budgets. He directed some of the most memorable films in the black cinematic canon, including “Boyz n the Hood,” “Poetic Justice,” “Higher Learning” and “Baby Boy.” Most recently, he was a co-creator of “Snowfall,” the FX television drama about the crack epidemic of the 1980s.

Singleton's work left an indelible mark on American cinema, particularly by providing a glimpse into the lives of young, black men and women in this country. Singleton expertly walked a fine line of showing black experiences that were familiar to black people, but were also eye-opening to white audiences who often ascribed negative portrayals to African Americans because of what they saw on the 6 o’clock news.

In his hometown of South Los Angeles, those portrayals were particularly damning at the start of the ’90s, when gang culture and violence were routinely blasted on TV screens. But Singleton flipped the script. Through his films, he showed the power of maintaining control of his narrative, skillfully showcasing the complexities of black life and helping to pave the way for African American actors, writers and directors to tell their stories as well.

Take “Boyz n the Hood,” a 1991 coming-of-age drama about three young black men growing up in Los Angeles, which was loosely based on his own life. The film features Tre (Cuba Gooding Jr.) and his friends Ricky (Morris Chestnut) and Doughboy (Ice Cube) as they navigate what was then called South Central Los Angeles, a neighborhood riddled with gangs, crime and police brutality. The film, Singleton’s directorial debut, raked in $57 million at the box office and was nominated for two Academy Awards: best original screenplay and best director. Singleton was the first African American and youngest person to be nominated for best director. In 2002, the movie was inducted into the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

“I think I was living this film before I ever thought about making it,” he told Vice in 2016. “Growing up in my early teens, I batted around with three friends, Jimmy and Michael, and our other friend who was also named Michael; his nickname was Fatback — he was heavy-set — and in the movie we called him Doughboy. As I started to think about what I wanted to do with my life, and cinema became an option, it was just natural that this was probably going to be my first film.”

The long-lasting impact of “Boyz n the Hood” came through again after Singleton's death, with tributes pouring in from friends and fans of the filmmaker and his work. Nia Long, who portrayed Tre’s girlfriend Brandi, called Singleton a “cinematic hero who loved everything black,” in a statement to NBC News. Chestnut, who made his feature film debut in “Boyz n the Hood,” told NBC News he owed “a 30-year career to John for giving a kid a chance to live out his dream.”

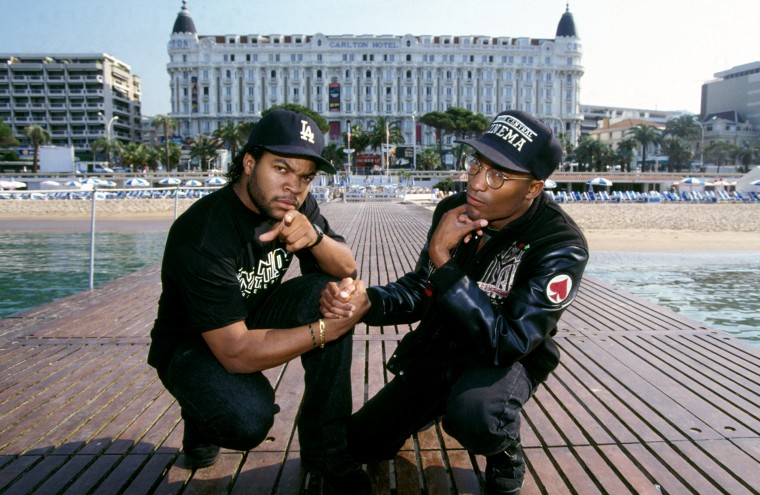

Ice Cube, who also grew up in South Los Angeles and who at the time of "Boyz" was part of the rap group NWA, also made his film debut with Singleton.

“Your passion for telling our stories from our point of view was more than an obsession, it was your mission in life,” Ice Cube said in a statement. “Your love for the black experience was contagious, and I would never be the man I am without knowing you.”

Black directors Ava DuVernay, Robert Townsend, Jordan Peele and Spike Lee also posted heartfelt tributes on social media.

Singleton’s legacy also centers on his commitment to his neighborhood, the cinematic backdrop to many of his most popular films. Singleton fell in love with films while watching the local drive-in from his mother’s apartment in Inglewood, The New York Times reported. When he was 11, he went to live with his father; in “Boyz n the Hood,” Furious Styles (Laurence Fishburne) is based on Singleton’s dad. A scene in which a black police officer tells Furious that he should have killed an intruder because “that would have been one less n-----”? True story, Singleton told Vice in 2016.

"I think people are still talking about 'Boyz n the Hood' because it's part of who they are,” Singleton told MTV News in 2011 for the film’s 20th anniversary. “Even if they're not from that environment, they really identify with those characters. People watch that movie and say, 'Wow, look at the journey of these characters,' and then they think about their own journey."

Darnell Hunt remembers seeing “Boyz n the Hood” in the theater in Los Angeles. He was a graduate student at UCLA, studying media and film, and he said he was blown away at the cultural authenticity of the film and how it portrayed black life in Los Angeles. The film’s timing was also impeccable, Hunt said, as it was released just months after four Los Angeles Police Department officers were caught on videotape beating an unarmed black motorist named Rodney King.

“‘Boyz n the Hood’ showed a range of different characters and took great care to express the humanity of the characters, even the flawed ones,” said Hunt, who is professor and dean of social sciences at UCLA. “It captured L.A. gang culture and it also showed black people in ways you don’t often see them depicted in mainstream Hollywood films — and for me, that was the big achievement of the film.”

Those characters were so relatable, Hunt said, because Singleton was so connected to the people living in South Los Angeles. In a brief clip, Singleton told the Television Academy Foundation that hundreds of people from his neighborhood watched as he filmed a simple scene on the first day of shooting “Boyz n the Hood.”

Beyond the characters, the movie's themes are simply timeless in their portrayal of race and social inequalities. And of course, it wasn’t all fiction, and much of it mirrors the realities across America today. In one particularly prescient scene, Furious Styles takes Tre and Ricky to see a billboard that is boasting cash offers for homeowners in their neighborhood.

"It's called gentrification," he explains to Tre and Ricky. "They bring the property value down. They can buy the land at a lower price. Then they move all the people out, raise the property value and then sell it for a profit.”

Currently, in Inglewood, residents are being pushed out of their homes to accommodate the L.A. Rams and Chargers stadium, The Los Angeles Times reported earlier this month. One resident received a notice that the rent for her two-bedroom apartment would balloon from $1,145 to $2,725.

Singleton died 27 years to the date of the start of the Los Angeles riots — in 2017, he directed the documentary “L.A. Burning: The Riots 25 Years Later” — after officers were acquitted in the beating of King. The day of the acquittal, Singleton was late to the set of “Poetic Justice,” his 1993 romantic drama starring Tupac Shakur and Janet Jackson, because he stopped by the courthouse to protest. News cameras caught him on tape talking about the failures of the criminal justice system when it comes to black victims.

“They put a black man in jail for kicking a dog, but they let a Korean woman off for shooting a young black woman,” he told a TV journalist, referring to the death of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, who was shot and killed by a convenience store owner in March 1991, one week after King was brutalized. “What are they telling our kids?”

Many of those “kids” King mentioned are now actively speaking out against similar cases of police brutality, just like he did. In recent years, activists and protesters have taken to the streets to decry the unjust killings of unarmed black men and women in the United States, in neighborhoods just like South Los Angeles. The fire and rage that burns inside those activists is exactly what drove Singleton's art.

“I wasn’t someone who took my anger and applied it inward; I turned it into being a storyteller,” he told the Guardian in 2017. “I was on a kamikaze mission to really tell stories from my perspective — an authentic black perspective.”