The Gullah Geechee people make up one of the oldest and most extraordinary communities in the United States. But if you’ve never heard of them, it might be because their history is often sifted out of textbooks, and the longevity of their culture is now in danger.

This distinctly African American community began on the eastern coastal islands — spanning from Florida all the way up to North Carolina in the 1600s. Slaves, mostly from West Africa, lived in complete isolation from the continental United States, separated by rivers, swamps and waterways that weren’t easy to cross.

“That created an environment for us to create our own culture, outside of when white American culture developed,” said Akua Page, a Gullah Geechee tour guide, entrepreneur and content creator from Charleston, South Carolina.

The Gullah Geechee people held on to stories, religious practices, farming methods, recipes and even formed their own language, separate from that of colonial Americans on the mainland. But now, the language, and culture, face a new threat.

“Gullah is now considered an endangered language, because my generation and younger — you’re not going to find us fluent in speaking actual Gullah,” Page, 28, said.

A 2005 environmental impact statement estimated there were 200,000 Gullah Gechee people in the southeast region of the U.S That number has likely shifted as the community continues to spread. There are large concentrations of Gullah Geechee people in cities like Jacksonville, Florida; Savannah, Georgia; and Charleston — which are close to the isolated islands where the culture was created. However, there is no official data on how many people currently speak Gullah.

When anti-literacy laws were lifted, allowing Black populations to learn how to read, write and attend schools for the first time, Page said, “a lot of people were being beaten that were speaking Gullah. So that historical trauma transferred over.”

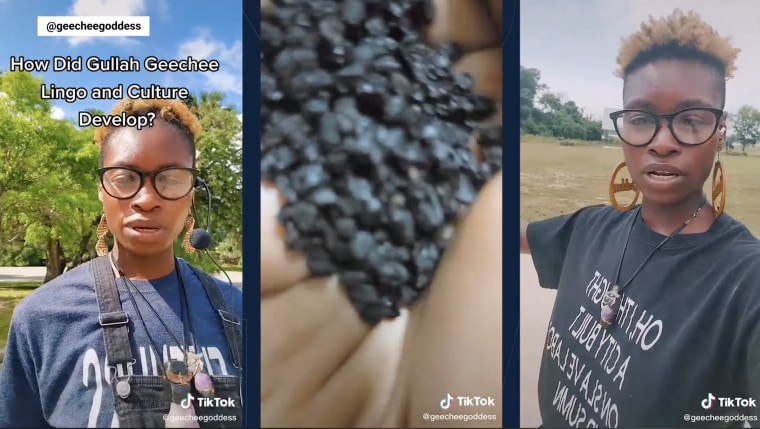

Page turned to social media to share Gullah stories with younger audiences. She’s had success, with more than 55,000 followers and 700,000 likes on her TikTok, and more than 440,000 views on her YouTube channel.

Viewers can find videos about traditional healing practices, such as how elders in their community put Spanish moss in their shoes to lower their blood pressure, and used elderberry tea to ease inflammation.

Page also explains the origins of the Gullah Geechee community and the disparities that her community faces, including not having access to the same high-quality rice that its ancestors cultivated centuries ago. Aside from the history lessons, Page offers several videos on Gullah translations and slang that are used in the Gullah Geechee community.

The feedback on these videos has been mostly positive, with many people writing in the comments that they’ve either never heard of Gullah Geechee culture, or they're interested in connecting more with their own ancestral roots in the community.

“I love TikTok. It has been so instrumental in the work I’m doing,” Page said. Her goal is to pass the torch, so that her culture, which has survived for hundreds of years, can keep going.

Although she’s now equipped with deep historical knowledge of her people, Page grew up in the foster system in South Carolina and wasn’t always with other Gullah Geechee community members. That made it challenging for her to understand her identity. She spent time at the Jenkins Institute, which was founded by a Gullah Geechee, the Rev. Daniel Jenkins, in 1891 (one of its early locations, in the landmarked Old Marine Hospital in Charleston, still stands today).

“I was exposed to it my whole life, but nobody really sat me down and was like, 'Girl, you’re Gullah Geechee,’” Page said.

Although it wasn’t clear to Page, her accent, vocabulary and mannerisms stuck out among her peers. “People are uneducated about the linguistic diversity of America, so when I came around to certain folks they just thought what I was speaking was broken or bad English. So I would get bullied a lot,” Page said.

“Now I’m an advocate for Black kids in foster care,” Page said, “I feel like I needed to experience that in order to lead me on this path and connect with my ancestors.”

But her concerns about the future of the Gullah Geechee community remain top of mind.

“In the work I’m doing, I’ve seen a lot of elders who are so passionate and enthusiastic about it,” she said, “I’m one person, you know, so I can’t do it all.”

Page says there is a pride and purpose in all the education that she does, especially in breaking things down in bite size pieces on social media. That pride is something she thinks about a lot around Juneteenth.

Many people use the day to reflect on freedom, as it commemorates the day in 1865 when slaves in Texas were notified of their freedom, two years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed.

“Our liberation is by knowing where we come from. ... I can tell just by the rice culture that we have down here and connecting back into Western and Central Africa and how we’ve been growing and cultivating that for eons,” she said, “We liberate ourselves by taking ownership.”

Page’s tours make their way to Riverfront Park, where visitors are given scenic views of the Cooper River, which is often speckled with people testing their fishing lines out on the docks. She ends her tours at a site called the Dead House, located right next to the river.

Historians say this brick building is likely the oldest structure standing in Charleston, but local residents speculate over whether anyone was ever killed at the site. Page notes that the land it sits on used to be part of an active plantation, and that the name is likely connected to that time period.

At the end of the tours, “we pour libation for the lives that were lost during slavery in Charleston,” Page said.

The homage is not just for “ancestors” known and unknown “who perished during he slave trade,” Page said, but also for “people who perish now, just dealing with racism and violence, but especially acknowledging those who experienced slavery and the names that people don’t really call out and have been forgotten.”

Page asks tour guests to read some of their names out loud, and to pour out a bit of water with each name. She says ashe after each one, which holds a similar meaning to amen.

“I feel like it’s our duty to tell our ancestors’ story, you know, we shouldn’t want somebody else to tell our ancestors' story,” Page said, “Going back to that African proverb, ‘Until the lioness tells their tale, the story of the hunt is always going to glorify the hunter.’ So I feel like you know, I’m that lioness. I’m gonna tell the story of my ancestors.”