The men filed into the chapel, pulled chairs into circles, and sat. Then this corner of New Jersey’s Bayside State Prison got quiet.

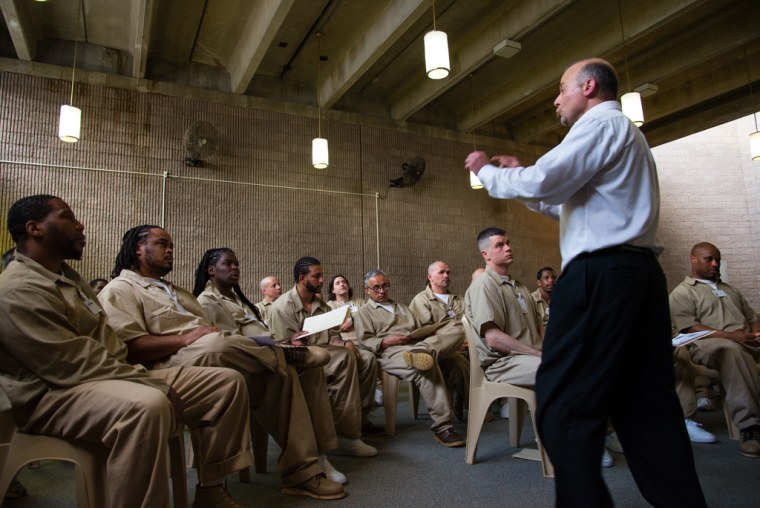

A short meditation opens each weekly session of Heart-to-Heart, a mindfulness and nonviolence program run at three east coast prisons. Silence, said founder Stephen Michael Tumolo, helps bring "present moment awareness.”

That’s where he believes transformation starts.

“One thing we have choice in is where our mind is,” said Tumolo. “Present moment awareness can radically alter one’s experience in the moment. And then it can radically reshape the next steps we take.”

Gossip, drugs, love—most of the outside world seeps through prison walls. In recent years, the nation’s growing interest in turning inward has crept in, too. Though there's no official tally, mindfulness programs now stretch from yoga at New York City’s Rikers Island jail to Transcendental Meditation at an Oregon state prison.

“This is a place where we can come and vent because you know we're under a lot of pressure,” said the man, who goes by Knowledge. “And they say pressure busts pipes.”

They represent a growing shift from tough-on-crime policies of the 1990s. Most seek to offer some daily calm inside and provide tools to keep prisoners from coming back. Research is scant, but small studies indicate they may help prisoners address anxiety, substance abuse issues and violence. There’s indication they could also help those released from prison from coming back.

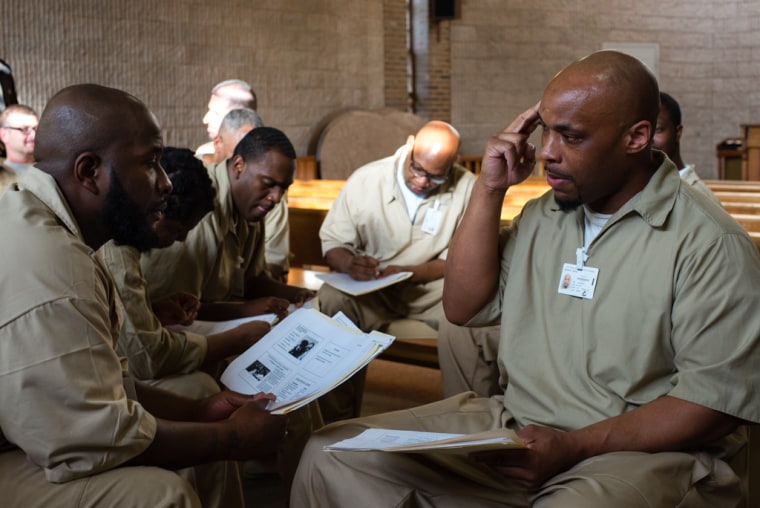

On a Wednesday afternoon, Efrain Rodriguez arrived to class, 34 months into a sentence for drug possession and four weeks into Heart-to-Heart’s 12-week program. Wearing the same uniform doesn’t mean prisoners see eye to eye, he said, but during these 90-minute classes men at Bayside don’t just keep the peace. They open up.

“You really let your guard down and you accept other people,” said Rodriguez, 42. “And then you familiarize because then, I can see me and him,”—he pointed at the man in identical khaki beside him—“We've got something in common.”

Officers fidgeted in the doorway as Rodriguez and about two dozen men breathed quietly. Late afternoon sun streamed through windows illuminating faces black, white and brown. Tumolo broke the stillness. He asked the men to share share why they had come that day.

“Self-improvement,” one man said. “Family,” said another. “Parole,” added a third, who had heard that participation might prove a plus in the arithmetic of release. A serious man with hair twisted into long cornrows raised his hand.

“This is a place where we can come and vent because you know we're under a lot of pressure,” said the man, who goes by Knowledge. “And they say pressure busts pipes.”

“Fill in the blank,” said Tumolo, a compact, energetic man with a goatee. “If I don't release the pressure what is that might that could happen?”

“The first couple of days I was like, ‘What the hell is this guy Stephen talking about?’ He wants me to express my emotions? I’ve never done that.”

“You could explode on your family during a phone call,” said Knowledge. “Somebody might say the wrong thing to you and you could react in a negative way in the yard.” And some “keep things bottled up for so long that you know, instead of exploding they implode.”

Prison is stressful. Researchers have found both prisoners and staff experience anxiety, anger and, sometimes, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. In this closed-in world, slights go unforgotten. Anger bubbles. Prisoners often talk of feeling treated as subhuman. Staff gets worn by being on perpetual alert. Then there is the weight of unbending routine.

PHOTO GALLERY: Inside Heart-to Heart Prison Meditation Program

Heart-to-Heart weaves meditation and yoga with theories of nonviolent communication, which posit that listening with empathy can address conflict by helping people find common humanity even in the most challenging moments.

Men in the program at Bayside talked of growing closer to God, and becoming more introspective. A soft-spoken Latino man with snow white hair, Luis Pozuelos said he had worked empathy into his daily life behind bars.

“At work I’ve had two strong disagreements in which the best decisions were to be humble and accept different views,” Pozuelos, 49, said in Spanish. “With that decision I gained better friends and not enemies.”

Heart-to-Heart traces its roots to Comienzos, a program founded in the 1980s by a pair of Catholic nuns in New Mexico. Tumolo worked there before returning in 2008 to his native south Jersey. After hearing about Comienzos, the chaplain at Bayside Prison asked Tumolo if he could start a program similar to the one he left out west.

"I hit the ground running. I came home a man on fire.”

Almost six years on, state officials said several hundred men at Bayside have been through Heart-to-Heart, which now also works in two federal facilities, in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

In 2013, when Khalil Williams walked into his first class at Fairton Federal Prison in New Jersey, he didn’t know what to make of it.

Williams was serving nearly eight years on an armed robbery charge. He had spent a decade “knee deep” in gang life. Feelings were not common parlance in his world.

“The first couple of days I was like, ‘What the hell is this guy Stephen talking about?’” remembered Williams, 36. “He wants me to express my emotions? I’ve never done that.”

More than a year after his release, Williams still meditates each morning. Then he leaves his apartment in the Bronx for his job working on sound stages. He’s enrolled in online college courses in psychology, and said he feels like a different man.

“It’s changed my entire perspective on things,” he said. “Before I got arrested, I would act before I think. Now I question every situation.”

Students both current and former talk about the program as a place to be heard. Some described it as the first time in their lives they felt listened to, and not something they expected to find just outside their cells.

“You have the officers who look at these people like they’re the scum of the earth,” said Curtis Moore, who participated in the program at Bayside. “Heart-to-Heart, it’s a different type of atmosphere. They really appreciate your humanity. You made a mistake but you’re not that mistake.”

Moore went to prison at 19 for aggravated manslaughter and he served 13 years. He credits openness he developed at Heart-to-Heart with the life that he has built on the outside. He found a place to live. He enrolled in college. He became youth counselor at the Urban League in Essex County, where his background proved an asset rather than an impediment.

“Before I got arrested, I would act before I think. Now I question every situation.”

“I’ve been out for 29 months—not even that long,” said Moore. “That’s the glory of it. I hit the ground running. I came home a man on fire.”

The men gathered at Bayside that Wednesday had been convicted of robbery and drug possession, sexual assault and murder. But like the nearly 2.3 million people who wake up incarcerated each morning, most will be released. They had visions of the person they wanted the world to see: A man of God. A genuine person. A strong black man. A caring father.

In that chapel encircled by concertina wire, Tumolo encouraged them to think about how being in the "present moment" might help them become that best self.

PHOTO GALLERY: Inside Heart-to Heart Prison Meditation Program

Standing in front of a whiteboard where Tumolo had scribbled the goals, desires and needs the men said had led to their incarceration, he paused for a moment. Then he described the desires that landed him in prison that day.

“I want a world in which each of you guys, your needs matter,” said Tumolo. “And I want a world in which you treat everyone else like their needs matter. Because we're all human beings. And that's a world in which we relate not head to head, but heart to heart.”

These photographs will also run on @EverydayIncarceration, an Instagram feed that visualizes the legacy of 40 years of mass incarceration.