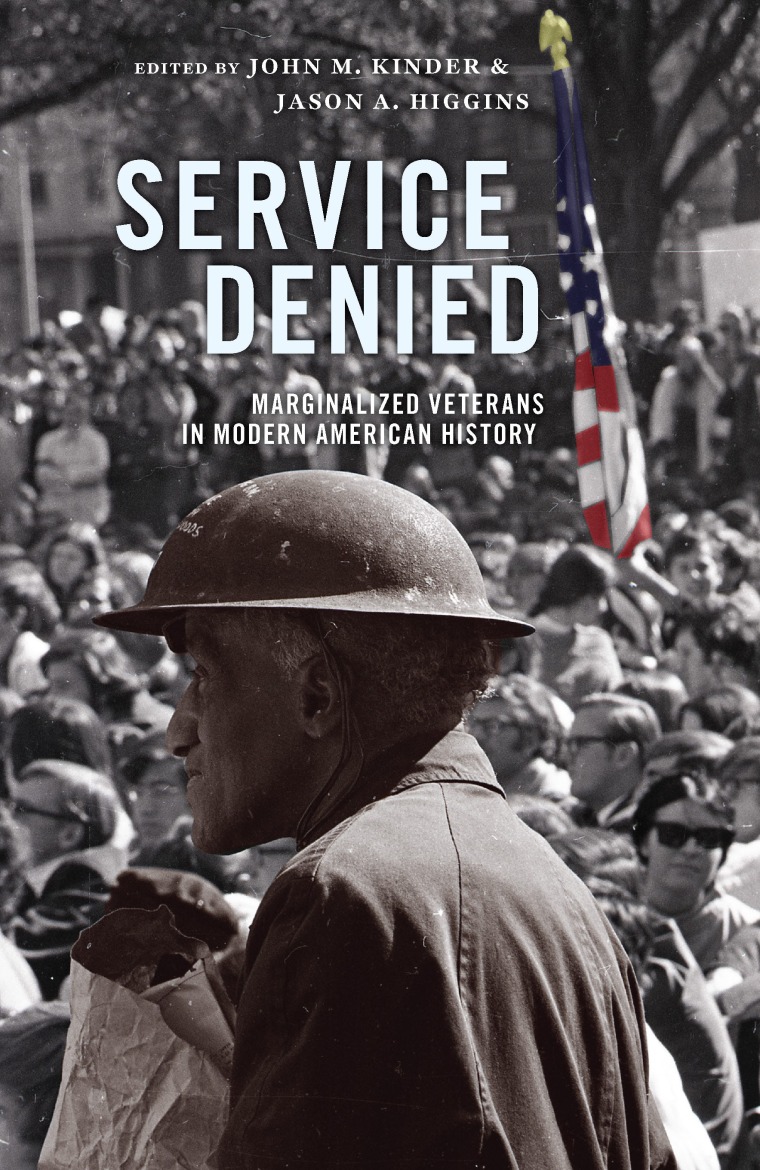

A new book explores how veterans of color have been affected by war across generations and the different ways the military further marginalized service members from minority groups.

Jason Higgins, a postdoctoral fellow at Virginia Tech, has been conducting oral interviews with formerly incarcerated veterans since 2017. With John M. Kinder, an associate professor of history at Oklahoma State University, the two co-edited “Service Denied,” which came out Friday.

One of the veterans featured in the book is David Carlson, 38, a sergeant in the Army National Guard who fought in the Iraq War and has dedicated his life to serving other vets and civilians in western Wisconsin. He said people who are making the transition from the military with post-traumatic stress disorder and other such issues need housing, employment and education at the same time, which is why he co-founded a peer mentoring organization.

However, before Carlson could focus on living a life of service, he needed to address some personal issues, like his struggle with PTSD.

Higgins says the intergenerational trauma that Carlson carries as a Black Iraq War veteran — and as the son of a Vietnam veteran diagnosed with PTSD — is a snapshot of the traumas many service members face after they come home from war.

Carlson’s father, Higgins said, was drafted under Project 100,000, which was a program that lowered entrance exam requirements for military service in 1965. It allowed the military to draft a disproportionate number of poor, undereducated Black men during the Vietnam War.

The initiative was presented as a way to give job opportunities and education to a generation of Black men, but, Higgins said, “only about 6 percent of those drafted under Project 100,000 gained any additional education or job training.”

In fact, Black service members recruited through the program were twice as likely to get killed in Vietnam compared with U.S. forces as a whole, according to the book, which cites a 1970 Pentagon study that did not account for the remaining years of a war that stretched until 1975. In addition, the number of less than honorable discharges increased dramatically, from 6,911 in 1970 to more than 25,000 in 1972, and more than half of those discharges were for Black service members, which stripped veterans of both medical and mental health care, as well as subsidized education and work training.

Decades later, Higgins’ interviews with Vietnam and Iraq War veterans show that mental health problems, including PTSD, traumatic brain injuries, military sexual trauma and moral injuries — a specific type of psychiatric trauma — have factored into veteran incarcerations.

After having served in Iraq, the younger Carlson found himself thinking he was still overseas, even though he was back in the U.S. as a civilian.

“My adrenaline was super high all the time,” he said, describing how he felt when he knocked out a man on New Year’s Eve 2010, after the man pushed his friend’s wife.

Carlson then took the man’s wallet, opened a tab at another bar and passed out in a cab the next morning before he was arrested. He was detained for eight days.

Carlson remembers getting released into a blizzard in a sweatshirt. And while walking just a mile, he committed three break-ins and burglaries, in which he stole some jackets and a computer, among other things.

“I’m in that state of mind where I’m willing to do whatever it takes to survive,” he said.

Carlson said he even became suicidal when he was in detention, and in 2011 he was diagnosed with PTSD. But he didn’t find the structure that he would ultimately need to get out of prison until another veteran stepped in and stuck with him.

The veteran who saved Carlson’s life

Michael Orban, an infantry soldier, was drafted for the Vietnam War in 1969 and spent his 21st birthday in the jungle by the Cambodian border. He has a Bronze Star, an Air Medal and a combat infantry badge.

It took three decades for Orban to seek treatment for suicidal ideation, which he eventually found at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Wisconsin. There, he said, he met other Vietnam veterans on the first day he committed himself to inpatient treatment. It felt like a homecoming.

“I was with other people who had experienced the same thing, who knew where I was emotionally, psychologically, spiritually, and I almost wanted to cry,” he said.

Now, he co-hosts a podcast for other veterans and has received an honorary doctorate from the Medical College of Wisconsin for his work on veteran suicides.

When Orban met Carlson about a decade after he was diagnosed with PTSD related to combat, he felt compassion because he saw himself reflected in Carlson’s condition.

“David sat down in a chair at the Greyhound bus depot in Milwaukee. He had a gash in his forehead and a gash in the back of his head from a fight,” Orban recalled. “He was dirty. He was starving. He had nothing in his pocket. He didn’t know who he was. He didn’t know why all of this stuff was haunting him the way it was. And he just started weeping.”

Orban helped him get a bus ticket home. And when Carlson was incarcerated, Orban stuck with him.

Now, Carlson finds himself on another side of the law. Having completed his first year at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, Minnesota, he is volunteering to help veteran defendants get second chances.

“I think what I’m doing now is actually my biggest contribution to my military service and to my country,” Carlson said. “Our service never ends. Once we sign that line and we give our oath and we ship out, we’ve taken on a lifetime of service.”