When Nicholas Papageorge stepped into a Washington Heights classroom in New York City to begin his time as a member of Teach for America Corps in September 2000, it was a day of firsts. As a white person who had attended private schools his entire life, Papageorge was not used to being considered the minority.

Statistics told one story – that these students, nearly all of color, were disproportionately likely to end up connected to the criminal justice system or not make it through college. But being in a public school classroom for one of the first times spun a different narrative, and Papageorge came to some realizations that would later shape his career.

“There is nothing wrong with these kids. These kids are great,” Papageorge, now an assistant professor of economics at Johns Hopkins University, soon realized. “They have difficult home lives for sure, but they are these rambunctious, clever, intelligent, bright, curious, kind and impressive kids. And I’m like, 'How are we failing them?'”

“One of the most damaging things that white teachers can say is that they don’t see color in their classrooms.”

As a new teacher, Papageorge couldn’t make sense of it. His colleagues agreed that something was wrong, but Papageorge wasn’t satisfied with the answers as to why. That’s when he decided he would dedicate the next years of his life exploring these questions.

The lessons he learned when he was just starting his teaching career have culminated in a new study called, Who Believes in Me? The Effect of Student–Teacher Demographic Match on Teacher Expectations.

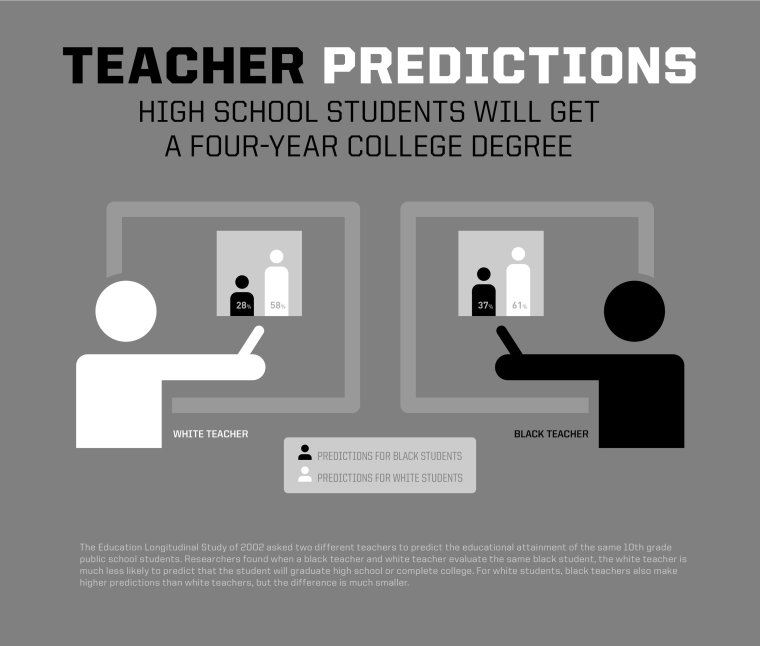

Supported by the American Educational Research Association and co-authored by Seth Gershenson and Stephen B. Holt of American University, the Johns Hopkins University study found that when looking at the same black student, white teachers are nearly 40 percent less likely than black teachers to predict that the student will graduate with a high school degree.

Additionally the study found that white teachers are 30 percent less likely to think their black students will finish a four-year degree at college.

Shanna Peeples, a high school English teacher in Amarillo, Texas who was named the 2015 National Teacher of the Year, said the conclusions drawn from the study did not surprise her. Peeples said she was simply disappointed the data supported what she already suspected was true.

“One of the most damaging things that white teachers can say is that they don’t see color in their classrooms,” Peeples said, who has taught in majority black and Hispanic middle and high schools since 2002. “They don’t realize that they’re erasing the experiences of their students.”

Peeples, who is Caucasian, knows this to be true because when she first began teaching, she was exactly that type of teacher who professed that she “didn’t see color.”

“My very first day of teaching middle school, the first student to meet me at my doorway was a six-foot tall, 12-year-old African American boy, who looked down at me and said, ‘What are you doing on this side of town, white lady? Are you lost?” Peeples recalled, knowing in that moment that her students didn’t feel connected to her. “They helped me to see there was white privilege I didn’t even know I had.”

Papageorge and his co-authors studied data from the Educational Longitudinal Study of 2002 which looked at 8,400 public school students in the 10th grade. Black and white teachers were asked to evaluate students and make judgments on the level of education they thought their students would achieve. The teachers’ predictions were essentially the same when it came to the fate of white students but differed substantially when it came to black.

Other findings of the Johns Hopkins University study include:

- When evaluating black male versus female students, non-black teachers were 5 percent more likely to think the male students wouldn’t graduate with a high school degree

- Black female teachers are more optimistic when predicting the future of black boys than teachers in any other demographic

- White male teachers are 10 to 20 percent more likely to have low expectations for black female students

Constance Lindsay, a professional lecturer in the Department of Public Administration and Policy at American University, is looking to collaborate with Papageorge and other researchers to examine how these dynamics play out in the long term. She said the wheels began to turn after reading the findings of the Johns Hopkins study.

“I don’t think we want to live in a world where only white teachers can teach white students and only black students can teach black students,” Lindsay said, who started looking at teacher diversity after reading reports that the number of minority teachers were declining. “I think we need to look at teacher preparation and training and ways we can mitigate the bias.”

RELATED: Report: Minority Teachers Are Quitting at Rapid Rates

Papageorge said it is impossible to conclude which teacher is “right.” Are black teachers being overly optimistic or are white teachers being overly pessimistic about these students’ futures? Still, the discrepancy between the white and black teachers’ predictions is alarming, and gauging which teacher is “right” gets complicated.

“Let’s say that I have a black student, and I basically tell him every day, ‘You’re not going to college,’ and I give all my resources to somebody else in the class, and then let’s say the kid doesn’t go to college, then it’s not clear that I was right,” Papageorge said. “It was a self-fulfilling prophecy. I made myself right by effectively making him not go to college because of my low expectations.”

The matter is undoubtedly a complex one, but Papageorge said a careful study is not necessary to realize that something is wrong. He said just looking at the proportion of white to black students that finish college is enough to know there’s a problem, and from an economist’s perspective, that's a red flag.

“Perfectly capable, smart, intelligent people are not reaching their full potential, and that’s a waste,” Papageorge said. “We’re throwing potential away.”