She started having suicidal thoughts at 11 or 12. She didn’t know the words to name it. She had no idea what it was, but she consistently had these urges to end her life.

“I just wanted to be dead,” she says.

One night when she was 24, and already long diagnosed with clinical depression, she succumbed to the feelings.

“I couldn’t suppress these thoughts anymore,” she recalls. “I had thought about ending my life for eight straight months.

“I texted a friend and said, ‘It would be better if I wasn’t here.’ That friend did not know that I had already taken substances in the hope that I would go to sleep and not wake up. And while I was waiting to die, the police showed up.”

T-Kea Blackman, now 29, survived that attempt and dedicated her life to helping others navigate the darkness of depression and mental health crises.

Suicide, long thought of something that affected other racial and ethnic groups, is fast becoming an epidemic in black communities, particularly among school-age children.

A recent study in the Journal of Community Health showed that suicide rates among black girls ages 13-19 nearly doubled from 2001 to 2017. For black boys in the same age group, over the same period, rates rose 60 percent.

Additionally, for children ages 5 to 12, black males are committing suicide at higher rates than any other racial or ethnic group, said Dr. Michael Lindsey, the executive director of New York University’s McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research.

“If suicide was a black phenomenon and all of a sudden there was an uptick in white kids committing suicide, there would be a national outcry,” Lindsey said on a panel, “Mental Health: A Hidden Crisis in Schools?” at this year’s Education Writers Association national conference.

It’s not just data points that are sounding an alarm.

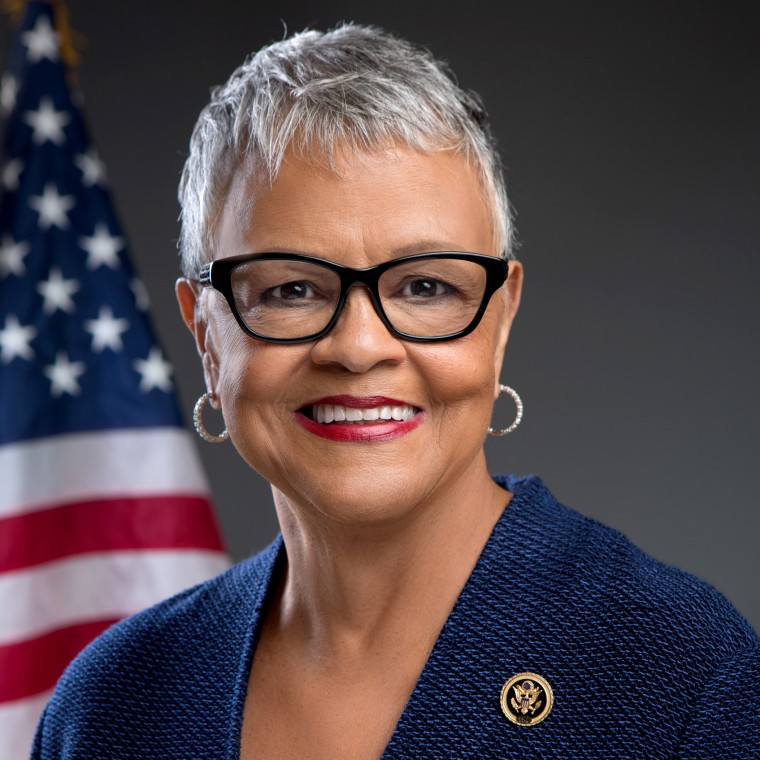

Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman, D-N.J., a member of the Congressional Black Caucus, began seeing more and more personal stories of youth suicide in her Facebook and Twitter feeds.

“I said to my staff, ‘We gotta do something about this’,” Watson Coleman said. “I don’t know to what extent we have control over anything, but the least we should be doing is raising the concern so that this issue could be addressed.”

Watson Coleman approached CBC Chairwoman Rep. Karen Bass, D-Calif., and together they created the Emergency Taskforce on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health.

Launched at the end of April, the task force has 15 representatives, including Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., and freshmen Reps. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn. and Ayanna Pressley, D-Mass.. There is also a working group, led by Lindsey, that includes clinicians, clergy, researchers and social justice practitioners. Also enlisted was actress Taraji P. Henson, a mental health advocate, who on numerous occasions has shared her own struggles with mental health.

“The more we get into this,” Watson Coleman said, “the more frightening the situation becomes to me, the more we recognize that suicide in general is a problem across communities, but it has a particular impact in the black and LGBTQ communities.”

The task force and working group are scheduled to present their findings in December. But Coleman says that so far, all the evidence for the spike in suicides points to multiple factors.

“The lack of access to mental health care,” she says. “Teachers who don’t know what to look for, or communities that don’t have the tools to deal with the issue.”

“Bullying has been identified,” she said, “and discrimination and harassment of the LGBTQ community have been raised as having an impact on how our young people process their life experiences.”

None of this comes as a surprise to Blackman, whose company, Fireflies Unite, addresses mental health issues that she notes are born out of childhood trauma. Her book, “Saved & Depressed: A Suicide Survivor’s Journey of Mental Health, Healing and Faith,” documents her struggle.

“My (suicidal) thoughts go back to my father being incarcerated for most of my life and my mother being verbally and physically abused,” Blackman said.

There were also cultural and community pressures that for years kept her fearful that she would be locked up or sent to “the crazy house.”

“I was told that I would have to go to therapy, but that therapy was for rich, white crazy people,” Blackman said. “I don’t fit the rich, white demographic.”

The response from the church, the foundational institution in most black communities, was troubling.

“I was told to speak in tongues for 20 minutes a day and that my suicidal feelings would go away, or my depression would go away,” Blackman said “I was told not to take my medication because that would make it worse or to just pray harder.”

Watson Coleman expressed the same concerns.

“You were always told, ‘You got Jesus on your side and you don’t need anything else, he will work it out for you,’” she remembers. “But mental health is an illness of the mind, and if you had an illness in your leg, like I did, and needed a new knee you go to the orthopedist.”

Blackman works to direct people with mental illness to the resources they need. She thinks one of the solutions is that all schools need to train their staff on mental health first aid, which is an eight-hour course where individuals can learn to better identify the signs of some mental health conditions, like depression and bi-polar and anxiety disorders.

“There are many signs if someone is having a mental health crisis,” she says, “and the major ones for children is if they begin to withdraw from regular activities, or if their grades begin to suffer. Another thing, if they start giving away possessions. Also, please monitor their social media, because sometimes it’s there that you will see what they’re going through.”

But the most important piece of advice, she noted, is not to dismiss what your child is saying and to listen to them, judgment free.

“Parents too often dismiss what their child is saying about how they are feeling,” Blackman said. “They say, ‘Oh, you have a roof over your head and clothes on your back. … You don’t have any real responsibilities.”

“We still pass down generation trauma,” Blackman said. “Depression is a disease, just like diabetes.”

Resources: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org

https://www.crisistextline.org

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources..