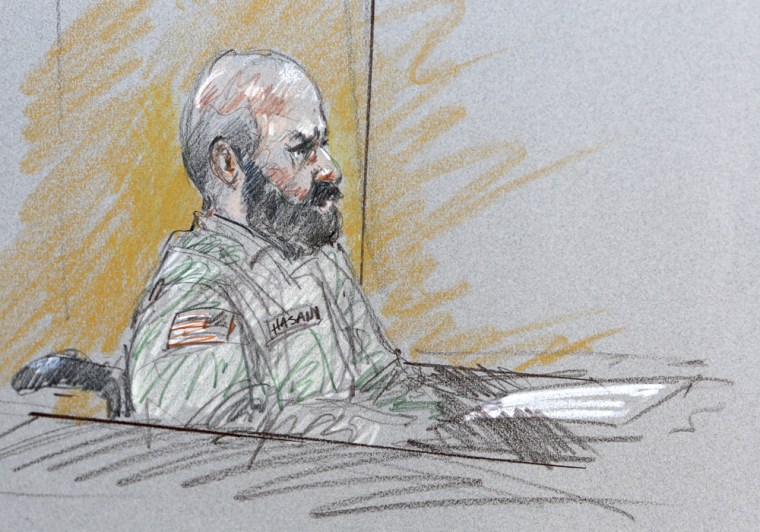

An Army psychiatrist accused of one of the worst mass shootings in U.S. history told jurors that "evidence will clearly show" that he was the gunman responsible for the rampage that traumatized the Fort Hood military base in Texas nearly four years ago.

But Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, who is representing himself in the long-awaited court-martial, also cautioned that the evidence wouldn't tell the entire story.

"The evidence will clearly show that I am the shooter," Hasan, an American-born Muslim accused of killing 13 soldiers and wounding 32 others on Nov. 5, 2009, told jurors in a less than two-minute-long opening statement, according to The Associated Press.

However, he added: "Witnesses will testify that war is an ugly thing. Death, destruction and devastation are felt from both sides, from friend and foe. Evidence from this trial will only show one side. I was on the wrong side, but I switched sides," Reuters reported.

The court-martial began under heavy security on Tuesday. A row of shipping freight containers, stacked three high, created a makeshift fence around the courthouse on the first day of the trial, which is expected to last several weeks, if not longer, according to the AP. Guards with long assault rifles stood watch outside the courthouse.

Many of the 32 who were wounded will appear on the witness stand during the trial, facing the man accused of wounding them.

Hasan is acting as his own defense attorney at the trial after twice dismissing his legal team. He told jurors evidence will also show "that we are imperfect Muslims trying to establish the perfect religion... I apologize for any mistakes I made in this endeavor," the AP reported.

The 42-year-old Hasan, shot by a civilian police officer and paralyzed from the waist down after the rampage, is confined to a wheelchair.

In his opening statement, military prosecutor Col. Steve Henricks said prosecutors would show that Hasan picked the date of the attack for specific reasons, although Henricks didn't reveal more details immediately, the AP reported.

Henricks also argued that Hasan chose a time when the large hall where he opened fire on the base would be most crowded.

Hasan meticulously planned the attack, the prosecutor said, even going so far as to muffle the sound of his weapon and bullets by stuffing paper towels into the pockets of his cargo pants on the day of the attack.

"All those fully loaded magazines do not clink, do not move, do not give him away," Henricks told jurors, all military officers, during his hour-long opening statement. "He sits among the soldiers he's about to kill with his head down."

Hasan zeroed in on soldiers and tried to clear the Soldier Readiness Processing Center of civilians, Henricks said, telling one civilian data clerk to leave the building because her supervisor was looking for her. The clerk apparently thought it was odd, but left anyway.

"He then yelled 'Allahu akbar!' and opened fire on unarmed, unsuspecting and defenseless soldiers," Henricks told the jury, using the Arabic phrase for "God is great!"

Hasan has admitted to the 2009 rampage, but was prohibited by a military judge from entering a guilty plea because prosecutors are pursuing the death penalty.

Death sentences are frequently overturned in military courts, according to the AP.

The first three witnesses of the trial were employees at Gun's Galore, a gun store close to the base in the central Texas town, where Hasan bought the pistol that was used in the shooting. The store manager, David Cheadle, told the court he showed Hasan how to assemble the gun while Hasan recorded him on video, Reuters reported.

When the weapon was presented as evidence, Hasan said, "Your honor, that is my weapon."

He was about to be deployed to Afghanistan when the massacre happened.

"Evidence will show that Hasan didn't want to deploy and he possessed a jihad duty to kill as many soldiers as possible," Henricks said.

Hasan told a doctor at the base: "They've got another thing coming if they think they are going to deploy me," Hendricks said.

The military judge in the case, Col. Tara Osborn, ruled last Friday that prosecutors can present evidence that Hasan searched for specific terms online in the days and hours before the attack, including "Taliban" and "jihad," which is defined by some radical Islamists as "holy war."

The government claims Hasan sent more than a dozen emails starting in December 2008 to Anwar al-Awlaki, a radical U.S.-born Islamic cleric who was killed by a drone strike in Yemen in 2011.

Hasan may cross-examine any witness, including survivors of the attack. Fort Hood officials have said he plans to only call two witnesses at trial, according to Reuters.

Hassan faces lethal injection if convicted of 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted murder. A unanimous guilty verdict is required for execution but even that decision would likely be subject to years — potentially decades — of complex appeals, according to Reuters.

Hasan's trial was initially slated to begin more than a year and a half ago, but legal quagmires have repeatedly delayed it.

The first judge in the case was ordered to be removed because of an appearance of bias. Hasan has also fought with the court to represent himself and to sport his beard, a violation of the Army's grooming standards, which he says he is doing as an expression of his religion.

He faces a panel of 13 senior Army officers — including nine colonels, three lieutenant colonels, and one major.

Staff Sgt. Alonzo Lunsford, one of the wounded men who testified Tuesday, recounted taking cover behind a counter inside the complex and watching Hasan unleash a hail of bullets into a crowd of nearby soldiers. Hasan then pointed his gun at Lunsford, striking him in the head and in the back.

Lunsford pretended to be dead as Hasan pursued other victims, according to the AP.

After Lunsford escaped through a back door, Hasan came outside and shot him five more times in the torso, he said.

“I can’t see from my left eye, blood is pooling under my head, my eye is swelling,” Lunsford said just a few feet away from Hasan, who sat quietly in his wheelchair. “I decided to run.”

Prosecutors played a recording of a stark 911 call from Michelle Harper, a civilian base employee, as she hid under a desk. An operator can be heard trying to calm her as gunshots and loud moans ring out in the background.

Harper said the moaning belonged to Pfc. Michael Pearson, who later died.

Lunsford earlier told the AP that the prospect of confronting Hasan face to face didn’t elicit fear in him.

"I'm not going to dread anything. That's a sign of fear," Lunsford said. "That man strikes no fear in my heart. He strikes no fear in my family. What he did to me was bad. But the biggest mistake that he made was I survived. So he will see me again."

But another survivor, Staff Sgt. Shawn Manning, feels differently.

"I have to keep my composure and not go after the guy," Manning, a mental health specialist who was preparing to deploy to Afghanistan with Hasan when he was wounded, told the AP. "I'm not afraid of him, obviously. He's a paralyzed guy in a wheelchair, but it's sickening that he's still living and breathing."

A helicopter transports Hasan nearly every day between Bell County Jail, where he is being held, to the Fort Hood base, and he lives under the watch of a private guard for at least 12 hours each day — all on the dime of the U.S. Army and American taxpayers, according to NBCDFW.com.

The daily helicopter rides are necessary because driving Hasan by car creates security concerns for the jail, NBCDFW.com reported.

But victims of the rampage told NBCDFW.com that the special treatment he receives doesn't match up with what they have gotten since the shooting.

Staff Sgt. Josh Berry, one of the victims injured in the shooting, committed suicide on Feb. 13, 2013, after years of battling post-traumatic stress caused by the massacre, his family told the station.

"He felt there were more considerations that were being given to the shooter that weren’t being given to the victims and he couldn’t understand," said Howard Berry, Josh’s father.

NBC's Daniel Arkin and Debbie Strauss contributed to this report. The Associated Press and Reuters also contributed.