In life, Len Bias was basketball's next great hope, contender for a crown that went instead to Michael Jordan.

In death, he became a trigger for the war on drugs.

Bias' 1986 cocaine overdose helped sparked a panic, stoked by false rumors and a high-stakes political campaign, that culminated in a law that swept thousands of low-level drug offenders — most of them young and black — into prison.

Thirty years later, America is still reeling from the impact.

The new law established mandatory minimum drug sentences, provisions that exacerbated racial disparities, led to an explosion in prison populations and helped lay the groundwork for grievances that erupted in anti-police riots in Baltimore last year and in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Those effects are now fueling a bipartisan reform effort.

"The law that flowed from this completely destroyed the federal justice system and tarnished the reputation of the whole American justice system," said Eric Sterling, who as a young congressional aide helped draft the legislation and has since worked to unwind its effects.

Fear and politics

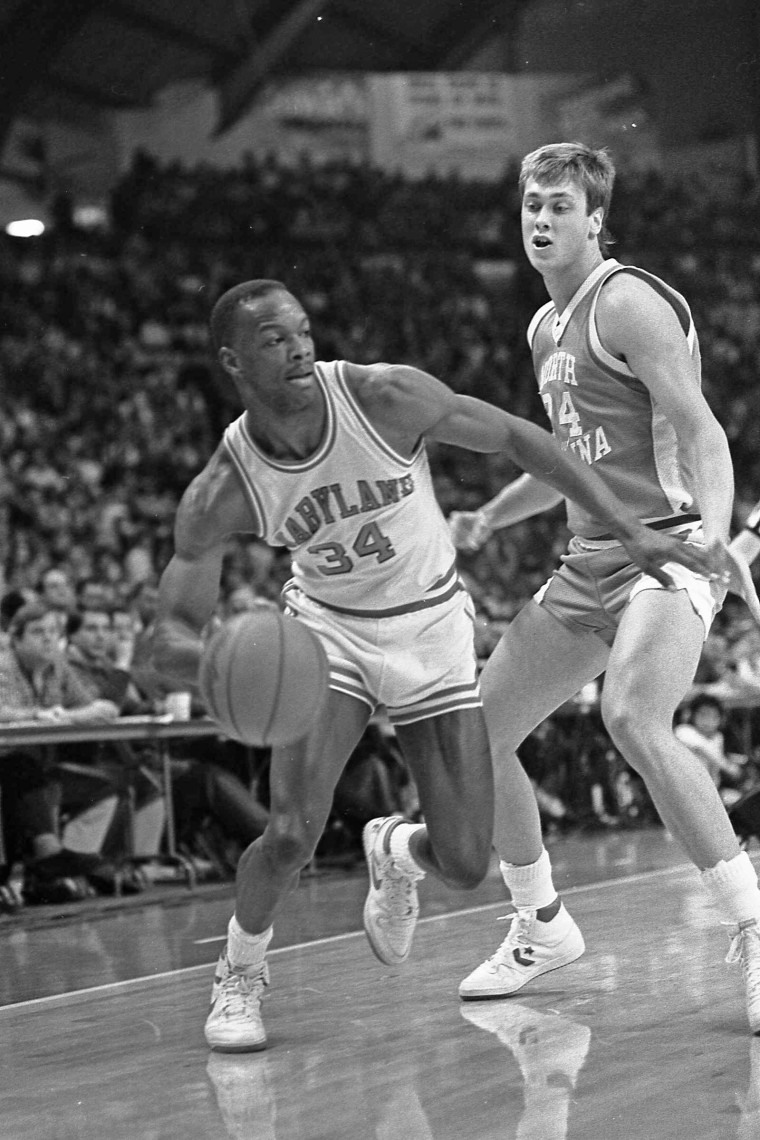

Sterling was a lawyer for the House Judiciary Committee when Leonard Kevin "Len" Bias, an All-American forward at the University of Maryland, died on June 19, 1986, two days after being drafted by the NBA champion Boston Celtics. A rumor, spread in the press, said he'd died smoking crack, a cheap form of cocaine that was being blamed for increasing crime and all sorts of social ills. It turned out that Bias had in fact snorted powder cocaine, but by the time that became clear the crack frenzy was in full flower.

Bias' death came as House Speaker Tip O'Neill of Massachusetts was leading Democrats' charge to outmaneuver Republicans in the approaching midterm congressional elections. O'Neill, a canny politician, heard his constituents clamoring about Bias and saw drugs as the path to victory. In four months — lightning speed in Congress — the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 became law.

The speed with which it was passed and signed by President Ronald Reagan meant there was little research into the bill's implications. No committee analyzed its key provisions, or held hearings, according to a later analysis by the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

The commission found that lawmakers were driven by the belief that drugs had become an "epidemic," with crack at the forefront. Reflecting breathless news accounts — Time named crack the "Issue of the Year" and NBC News called it "America's drug of choice" — Congress saw the drug as more dangerous, more addictive and more attractive to young people than powder cocaine. Most of those assumptions turned out to be untrue, although experts do blame crack in part for a rise in crime during that era.

Bias "became the face of the urgency for this effort," Sterling said.

'Dark chapter'

The law's most lasting legacy was a set of mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes, which Congress had repealed 16 years earlier. They were weighted heavily against crack, requiring only 5 grams to trigger a five-year prison sentence, compared to 500 grams for powder cocaine. The sentences rose to 10 years with 50 grams of crack and 5,000 grams of powder. Other drugs had their own required penalties.

The goal was to impose long prison terms on high-level dealers, but the hastily drawn provisions were based on little real-world evidence, researchers have since pointed out. The amounts fell far below what many kingpin-level traffickers handled, and the laws were more often used by cops and prosecutors against street-level operatives, including people tangentially involved in the drug business. Enforcement fell mainly on poor residents of inner cities, where dealing was more likely to be done in the open, and where police already focused their patrols. Later studies showed that whites and blacks used crack at roughly the same rates.

"It was a real low point and dark chapter in the war on drugs," said Michael Collins, deputy director of the Drug Policy Alliance's Office of National Affairs. "It was a point where hysteria dominated over evidence and it was really the catalyst for a lot of the prison problems we are tryingto reform today."

Kevin Ring, vice president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, said that once drug crimes had mandatory minimums, pre-determined penalties for other crimes followed, including illegal possession of guns, immigration violations, identity theft, sex crimes, fraud. "The '86 act has caused so much damage because it ratcheted up sentences for everyone," he said.

Unimagined legacy

Among the thousands caught in the new legal trap was Derrick Curry, a childhood friend of Len Bias, and his younger brother, Jay, who was murdered in 1990. Curry, like the Bias brothers, was a star basketball player at Northwestern High School in Hyattsville, Maryland. But after struggling in college, Curry returned home and began hanging out with friends involved in the drug business. Federal agents investigating the crew pulled him over in a car that contained a large rock of crack. He had no criminal record, but mandatory minimums forced a judge to sentence him to more than 19 years in prison. Bill Clinton pardoned Curry in the waning days of his presidency in 2001.

Curry said last week that the anniversary of Bias' death — and the reminder of what it wrought — stirred up all sorts of regrets and what-ifs. "So many people think ... Len Bias and his legacy (were) just basketball, and a lot of people don't know the impact his death caused — in so many peoples' lives around him and (those of) people who didn't know him or had anything to do with him," Curry said.

In 1985, the year before the Anti-Drug Abuse Act passed, there were about 35,000 people in federal prison, 9,500 of whom were in on drug charges, according to federal data analyzed by The Sentencing Project. Today, according to the U.S. Bureau of Prisons, there are about 195,000 federal inmates, with more than 85,000 serving time for drugs. About three-quarters of drug offenders in federal prison are black or Hispanic, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

A similar trend unfolded in state systems. The combined number of state and federal inmates climbed from 715,00 in 1990 to 1.5 million in 2014.

{

"ecommerceEnabled": false

}Keeping so many people behind bars has contributed to a dramatic decline in crime rates. But it has come at a steep cost.

Researchers say the era of mass incarceration has profoundly damaged American society, particularly for minorities, the poor and residents of inner cities. Millions are now unable to hold steady jobs, maintain housing, keep their families together or vote.

Coming 'full circle'

There have been some incremental changes. In 2010, the Fair Sentencing Act refined the crack-powder penalty ratio from 100-1 to 18-1 — an improvement that critics say still reflects the arbitrariness of the original law. The Sentencing Commission has loosened some of its guidelines tied to mandatory minimum laws, allowing thousands of nonviolent, low-level drug offenders to leave prison early. President Barack Obama has granted clemency to many others. And his Justice Department has ordered prosecutors to focus on high-level dealers.

But the major goal remains unfulfilled: passage of the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, which would allow judges to impose shorter prison terms in certain scenarios — and make the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive. It is supported by Republicans and Democrats, but not enough to overcome election-year squabbling.

"Now we've come full circle, 30 years later, to realize that (the Anti-Drug Abuse Act) was not a smart move," said Inimai Chettiar, director of the Justice Program at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York.

The reformers include Eric Sterling, who left government soon after his experience with the 1986 law and formed the The Criminal Justice Policy Foundation, which advocates for a new American drug policy. They also include Curry, who joined Families Against Mandatory Minimums and speaks publicly about his experience.

Then there is Lonise Bias, Len's mother. The death of her two eldest sons left her seeing "nothing but utter darkness," she said last week. But then she found purpose by waging her own war on drugs — not to lobby for sentencing reform, but to uplift children.

She is a motivational speaker, spreading what she calls a "message of hope" based on encouragement, compassion and good decision-making.

On Sunday, the 30th anniversary of Len's death, Lonise Bias will gather her two remaining children and her five grandchildren in Maryland and celebrate what she has, rather than what she's lost.

"We're going to have a ball," she said.

They'll finish the day by watching game seven of the NBA finals. And try not to think about what might have been.