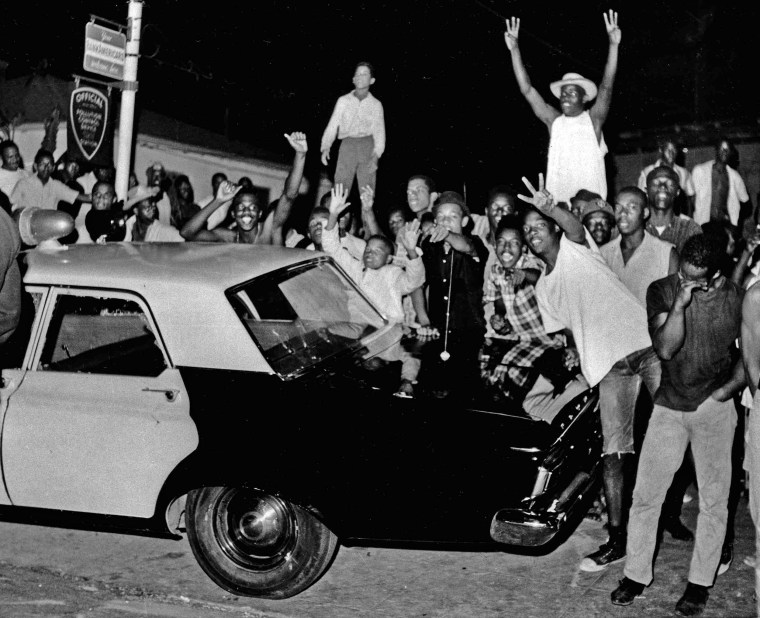

For more than 50 years, the Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts has been known primarily for its combative relationship with police.

But lately something's changed.

A rare partnership between cops and residents has begun to dissolve the chronic hostility that fueled a violent 1965 uprising and has plagued Watts ever since. Violence, including homicides, is down dramatically in the neighborhood, police say. But beyond the statistics, advocates see the possibility of a deeper transformation in how a skeptical public views police — and vice versa.

Watch Dateline's "On Assignment" on Friday at 10 p.m. ET to see Lester Holt take viewers inside a new way of policing Watts.

The effort is driven by the Watts Gang Task Force, created 10 years ago following a spasm of deadly gang-related shootings. Seeking a way to turn the neighborhood around, the group, made up of former gang members, relatives of gang members and parents who'd lost children to gang violence, agree to meet with police to talk solutions.

Related: 50 Years Later, Watts Remains Poor, Underserved and Defined by Race

The first encounters, brokered by a city councilwoman in early 2006, didn't go far.

"It was ugly," Donny Joubert recalled. He is the task force's vice president, a lifelong Watts resident who left "the life," or criminal underworld, to become an activist. "It wasn't no shake my hand and sit down and drink coffee, eat doughnuts. Wasn't none of that. It was us pointing out the hurt and the anger part of how we was treated with law enforcement."

But, slowly, the task force and the cops hit on a common goal: getting ahead of the retaliatory feuds the drove much of the neighborhood's violence. That required each camp to offer something to the other: the Watts representatives agreed to go to police with information about brewing trouble, and the police agreed to listen and act in a way that respected the community. That also meant acknowledging the pain police had inflicted on the community over so many years.

Police Sgt. Emada Tingirides, who grew up in Watts, started with an apology and a prayer.

That gesture spoke volumes.

"To hear a officer apologize for what took place over the years, and then just wanna pray about it, that's huge for our community," said Joubert, the Watts activist.

In 2011, civil rights activist Connie Rice and the LAPD, along with the city's Housing Authority, created the Community Safety Partnership, bringing together members of the public and the police to share information on street rivalries, ongoing criminal investigations and civilian complaints. Cops assigned to the group focus on building relationships over enforcement — counseling at-risk boys, tutoring students, leading a Girl Scout troop, founding a football time the brings together kids from rival gang territories.

The goal is to get the officers to see the community as a partner and not just someone they're responding to because it's your job," Tingirides said.

When police need help quashing violence, they turn to the Watts Gang Task Force, whose members head into the streets to calm feuds and debunk dangerous rumors.

But don't call them turncoats.

"It's not about snitching. It's about your babies. It's about your grandmothers," Joubert said. "It's about these innocent folks that's walkin' down the street, don't have anything to do with this, and catching a bullet that don't belong to them. That's who this is for."

They didn't realize it at first, but the alliance has become a test case in a growing field of research that emphasizes "procedural justice," which encourages police officers to be more empathetic and less judgmental in their everyday encounters with the public. If done properly, advocates say, it could reduce crime, improve witness cooperation and help prevent the kind of turmoil that has plagued Watts — and, more recently, Chicago, Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri.

The method de-emphasizes aggressive "hot spot" enforcement techniques like stop-and-frisk, which tends to target young minority men in poor, high-crime neighborhoods who in turn develop deep resentment toward the criminal justice system. The new strategy seeks to rebuild trust, by making the public see police as trustworthy, and their actions as acceptable — banking goodwill that could help prevent not only gun violence but also public unrest in the event of a cop shooting someone.

Related: Can Smarter Police Work Prevent Another Ferguson?

Bryan Stevenson, a civil rights lawyer who is a member of President Barack Obama's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which advocates for trust-building initiatives around the country, said the Watts experiment showed that change is possible even in communities where distrust of police is widespread.

"Watts is a perfect place to begin something new, something different, to begin thinking about how we might change the identity of the police," Stevenson said. "And if we can see progress, even small progress, in a community like Watts, then we can actually become hopeful about what policing might do in the 21st century."

A key part of the process involves police accepting some responsibility for the rupture, Stevenson said.

"And that's what excites me, actually, about some of the progress that we've seen in that community," he said of Watts. "We began to see police leadership say, "You know what? We have failed to respect the people in this community. We have failed to understand how our policies have created legitimate distrust, and now we've got to do something very, very different.'"

Michael Cummings, a former gang member known as "Big Mike" who now does street intervention work for the task force, said he's noticed that small changes in police behavior have outsize impact on the community.

Like simply talking.

"That go farther than anything," he said. "For a person to come and say, 'Hey, how you feelin' today, Big Mike? Everything all right?' Or instead of just driving by in a police car and mad-doggin' you. You know? Or just lookin' at you crazy. Or whatever. I mean, just a good conversation is good, you know? It's kinda like a changin' of the guards."

Phillip Tingirides, commander of the police department's South Bureau — and Sgt. Emada Tingirides' husband — said it would have been impossible to achieve anything without first talking and listening. At the same time, he had his officers, many of them hardened by years of anti-gang work, visit local schools to participate in reading programs, an experience that "humanized" the community for them.

"We as leaders, we have to just keep talkin'. Just keep talkin'."

Eventually, Tingirides he said, the collective mindset began to shift. When the police department created the Community Safety Partnership in late 2011, a 45 percent drop in violent crime followed, he said. There have been slight ups and down since, but that original drop has been sustained, he said.

People on both sides of the experiment acknowledge that the new balance remains fragile. Watts is still poor and lacking economic opportunity, still mostly minority (though now it has a Latino majority), still suffers from violence and still bears the weight of history.

In that environment, all it takes is one poorly handled arrest, or use of force, to set things back.

"It's a work in progress," said Perry Crouch, a task force member who lived through the 1965 unrest. "Young people (are) still fearful. They don't trust the police. But we as leaders, we have to just keep talkin'. Just keep talkin'."