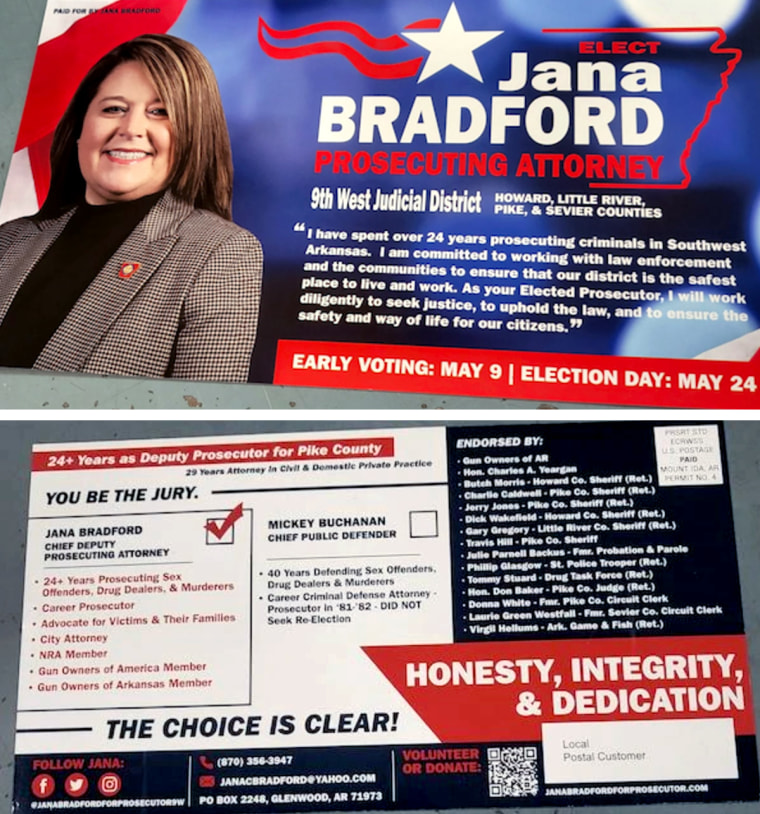

GLENWOOD, Ark. — Last year, while campaigning for the top prosecutor’s job in the rural district that surrounds this close-knit river town, native daughter Jana Bradford cited a tough-on-crime record that she said had brought the worst offenders to justice and comfort to their victims.

“The most important thing that I’m able to do is relate to our victims,” Bradford, a part-time deputy prosecutor in Pike County for more than two decades, told a crowd at a Rotary club meeting. “The child who has been molested by her parents, I’ve held her hand before she testified.”

But time and again, Bradford used her clout and legal skills behind the scenes to assist her pedophile uncle, according to a paper trail of letters and other legal records.

Over the years, she helped her uncle Barry Walker try to get a pardon from the governor for his first felony sexual abuse conviction in another Arkansas county, vigorously disputed a girl’s abuse allegations when he faced more possible charges and tried to get his name removed from Arkansas’ sex offender registry, records show.

Bradford’s efforts to assist Walker have surfaced in recent months as part of a swirling scandal in the wake of what some legal observers describe as one of the worst pedophilia cases in Arkansas history.

Last June 9, just 16 days after she won election as chief prosecutor in a four-county judicial district, investigators from the state and county, responding to new allegations from three girls, seized a cache of more than 400 homemade videos and thousands of photos and downloaded images of child pornography from Walker’s residence and arrested him.

The videos dated back a quarter century and captured Walker committing hundreds of acts of rape and other sex crimes on dozens of pre-pubescent girls, ages 2 to 14 — including a 4-year-old girl whose claims Bradford had vigorously disputed to a neighboring prosecutor years earlier.

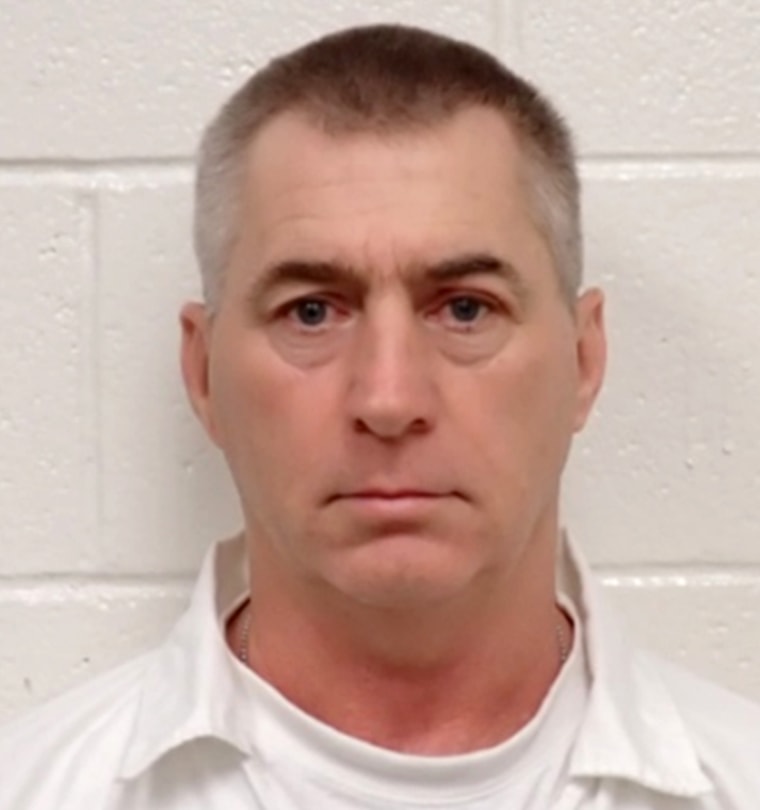

Four months later, Walker, 59, who ran a successful construction business, pleaded guilty to more than 100 felony counts in two counties related to raping or molesting 31 children, some repeatedly. He received 39 life sentences totaling 1,710 years in prison with no chance for parole.

Since his conviction in October, investigators have shifted their focus to Walker’s closest relatives and associates, amid allegations that they enabled Walker to keep preying on little girls for years.

Another of Walker’s nieces and his former longtime girlfriend each have been charged with felony counts of permitting child sex abuse, while Walker’s brother faces a misdemeanor charge of failure to report child sex abuse, court records show.

The special prosecutor overseeing Walker’s case and related ones, who was assigned in part due to Bradford’s conflicts of interest, said in a recent interview that a criminal investigation of “secondary targets” remains ongoing. Neither the prosecutor nor a state special agent leading that probe would say whether Bradford is among those targets.

A growing number of Walker’s victims, meanwhile, have joined a lawsuit that lays out a litany of explosive claims alleging a broader scheme and cover-up orchestrated by the child rapist’s “inner circle,” including Bradford.

“You don’t rape this many girls this many times in a small Arkansas town unless someone is running interference for you,” said David Carter, a Texarkana lawyer representing at least 14 of the victims or their parents and guardians.

The lawsuit includes allegations that Walker’s relatives and a former girlfriend intentionally delayed reporting two girls’ sex abuse claims last year to avoid hurting Bradford’s election chances. Following Walker’s arrest, the lawsuit alleges, his family schemed to hide Walker’s business assets and property in case any of his victims later sued.

The lawsuit also details Bradford’s repeated legal efforts over the years to protect and defend her uncle. It contends she wouldn’t allow her own daughter to be left alone with him, but failed to warn other parents that he was a sex offender who posed danger to their children.

Bradford, 54, a married mother of two who has not been charged with a crime, remains the prosecutor for Arkansas’ Ninth West Judicial Circuit. She did not respond to messages left by phone, email or at her downtown Glenwood office, where she displays a sign reading, “Honest Lawyer.”

Erin Cassinelli, an attorney representing Bradford in the civil case, said in an email to NBC News that Bradford isn’t doing interviews and is “instead focusing on litigating the issues in court.” Cassinelli said all of the lawsuit’s allegations about Bradford are “absolutely false,” and have not been verified or supported by factual evidence.

“Ms. Bradford denies in the most emphatic terms possible that she knew Barry Walker was molesting children or that she did anything whatsoever to conceal his depraved behavior,” Casinelli’s email said. “Since Ms. Bradford did not even know about Barry Walker’s continuing criminal acts, she certainly cannot be held responsible for his actions and the harm he caused.”

Walker did not respond to a letter sent to him in prison. His attorney in the civil case did not return a phone call.

One of Walker’s victims, now 22, said in a recent interview that she was afraid and ashamed to tell anyone about what Walker did to her as a child during playdates and slumber parties at his home. But she added that she believes those around Walker knew — and could have stopped him years earlier.

“The people who knew about Barry are equally complicit in what happened to me and all those other girls,” said the woman, who spoke with NBC News on condition of anonymity. “Every adult that was around, honestly. Nobody did s---. They failed us.”

Decades of allegations

In February 1999, Walker was a married Army veteran and ex-Air Force flight surgeon practicing medicine in Fort Smith, Arkansas, when an 8-year-old girl told her mother that “Dr. Walker had touched her in ways that made her feel uncomfortable,” according to charging papers.

Walker, then 35, and his wife had been over to the home of the girl’s parents for dinner. At some point during the evening, when he and the girl were alone in a home library, Walker sexually assaulted her, the court records say. The girl later told an investigator Walker also had “rubbed her privates on two previous occasions.”

A few months after he was charged with two felony counts of child sexual abuse, Walker’s wife divorced him. In March 2000, he pleaded no contest and was sentenced to five years in prison. Following his conviction, the state required Walker to register as sex offender and his medical license was revoked.

In 2001, after serving only about 11-½ months, Walker was paroled early for good behavior, a state Department of Corrections spokesperson said. He returned to live near his hometown of Glenwood, a 2-1/2 hours’ drive south from Fort Smith into the rolling pastures and ragged pine stands of rural Pike County — three counties away from where he’d been convicted.

Before his release, court records from his 2000 criminal case show a state psychologist and counselors had assessed and advised him that, to avoid re-offending, he should refrain from alcohol, attend regular therapy sessions and avoid being alone with children.

But Walker quickly blew off all of those recommendations — and his family members knew it, the victims’ recent lawsuit says.

Walker initially moved into a house within an enclave of homes along a wooded, gravel road just outside of town, where several of his relatives lived, records and interviews show. He started his own landscaping business about a year later and moved a few miles away, into an isolated rambler surrounded by pastures.

By then, Bradford was several years into her career as a part-time deputy prosecutor in Pike County, with a private practice on the side.

According to the lawsuit, she and other family members regularly “saw prepubescent females riding in Barry’s truck around Glenwood, riding horses with Barry at the fairgrounds, hanging out at Barry’s house and regularly spending the night,” but they did nothing to intervene.

During weekly family meetings, Bradford and at least two of Walker’s siblings discussed “how it was strange how Barry always had young girls around him,” despite being a registered sex offender, the lawsuit states.

New claims of sex abuse surfaced against Walker in February 2004, when a 3-year-old girl reported he had abused her, prompting the Arkansas State Police Crimes Against Children Division to open an investigation, a state sex offender assessment report shows.

Six months later, in August 2004, court records show Bradford helped prepare Walker’s application to the governor seeking “executive clemency” for his 2000 child sex abuse conviction. In his application, Walker wrote: “I would like a second chance to be a fully productive citizen of this state and practice medicine again in rural Arkansas.” The request was later denied by then-Gov. Mike Huckabee.

Over the next several years, Walker ran a landscaping business and then built a construction firm that became a thriving enterprise.

Meanwhile, more allegations surfaced, leading to more investigations. Girls came forward in 2006, 2010 and in 2014, the sex offender assessment report shows.

Based on a 2014 allegation involving the sexual abuse of a 4-year-old girl, Walker was arrested and booked into jail later that year, court and police records show. Bradford and other family members posted his $25,000 bond, hired a lawyer for him, paid his employees and kept his business running, the lawsuit says. The state police division made a referral to charge Walker, but that referral was overturned on administrative appeal, records show.

Why none of the other allegations resulted in charges against Walker isn’t fully clear because most of the records are under seal, said Carter, the victims’ attorney.

Bradford clearly was aware of various reports of sexual abuse against her uncle over the years, Carter said, and argued in the lawsuit. “She was actively working to protect her uncle against these claims even while she was a deputy prosecutor,” he said.

In response to the 4-year-old’s claims in 2014, Bradford sent a letter disputing them to Blake Batson, then the top prosecutor in neighboring Clark County, where her uncle lived. In it, Bradford referred to a private polygraph test she had Walker take, accused the girl’s parents of concocting the claims and contended that Walker never had been alone with the girl.

Batson didn’t charge Walker in 2014.

Now Clark County’s circuit court judge, Batson last year presided over Walker’s multiple convictions and sentencing in that county, including his guilty plea to raping the same 4-year-old girl.

During Walker’s sentencing hearing in October, the girl, who is now 13, stood to face him in a packed courtroom and read aloud a statement.

“You made my whole family turn against me, and think I was lying and imagining all of it,” she said. “And they trusted all of you people over me. That hurt just as bad as raping me.”

‘The falsest claim ever’

Two years after Bradford disputed the 4-year-old girl’s claims to Batson in 2014, Walker, through his business, bought a secluded five-acre plot on a dead-end road, directly across the highway from his family’s enclave outside of Glenwood, property records show.

On it, he later built a sprawling warehouse with an attached residence, where he lived.

In 2018, Bradford sought to get Walker’s name scrubbed from Arkansas’ sex offender registry, writing that he met the necessary criteria: It had been more than 15 years since his release from custody, and he wasn’t likely to pose a threat to others. In a formal letter accompanying the petition and sent to the prosecutor in Sebastian County, where Walker was convicted in 2000, Bradford identified herself as a deputy prosecuting attorney.

Bradford’s contention that Walker wasn’t dangerous “may well be the falsest claim ever made in a legal filing in the State of Arkansas,” the victims’ lawsuit later said.

In response to Bradford’s petition, the state sought to reassess Walker as a sex offender. After Walker failed a state-ordered polygraph in 2019 and a risk assessment administrator took into account the various claims and investigations, she issued a finding that his community notification status should actually be increased.

Bradford blasted the administrator’s finding in a December 2019 letter. She disputed that any claims were even documented in 2004, and contended “each and every one of the other alleged investigations were all unsubstantiated.”

“There’s not one scintilla of evidence to support increasing the community notification level of Mr. Walker,” Bradford added, contending that since his release from custody in 2000, he had been a “productive citizen” who’d “supported the economy and provided employment to many persons in the area.”

To bolster her argument, Bradford noted that Walker already had passed the private polygraph given to him in 2014 and included a report from the polygraph examiner. It shows he asked Walker only two questions related to touching the girl who had accused him.

A state panel that reviewed the administrator’s finding at Bradford’s request upheld Walker’s heightened sex offender status in 2020, records show.

According to Cassinelli, her attorney, the work Bradford performed on Walker’s behalf was done “in her capacity as a private attorney” and “included routine matters handled by attorneys for clients in jurisdictions around the country.”

“There is no basis to suggest she thereby became responsible for the acts of another person,” Cassinelli said in her email.

Fallout for Walker’s inner-circle

By early May last year, Bradford’s mother and an uncle learned from one of her cousins, Brandy Cox, that two more girls had said Walker sexually abused them, according to the lawsuit.

None of them reported the allegations to law enforcement “because of the political ramifications reporting Barry would have on Jana Bradford’s chances of being elected the prosecuting attorney,” according to the lawsuit, which does not allege Bradford was directly involved in those conversations.

About two-and-a-half weeks after Bradford won her nonpartisan race for prosecutor, Cox took the two girls to state police to report their allegations against Walker.

That led investigators to get a search warrant for his home and warehouse, where they discovered a hard drive with the videos and photos, along with a baggie of cocaine and seven firearms, including two fully automatic submachine guns.

Officers found most of the incriminating items in a horse trailer parked outside of Walker’s home, a probable cause affidavit states. Walker may have been “on high alert” for a police search after at least one family member had told him about the girls’ allegations, said John Jones, a police agent leading the criminal investigation.

Following Walker’s arrest, Cox admitted to an investigator that one of the girls had reported to her that Walker had molested her six years earlier, but Cox hadn’t acted on those claims, according to a probable cause affidavit for Cox’s arrest. Cox added that after telling other family members about the girls’ latest accusations, Walker had threatened to have her arrested, and “offered her a house, $10,000, and other considerations not to go to the police,” the affidavit said.

Nonetheless, Cox agreed to keep allowing the two girls to stay overnight alone with Walker, the affidavit says.

In December, Cox was charged with felony permitting sex abuse of a child. Cox did not respond to messages seeking comment for this article.

Barry Walker’s brother, Bryce Walker, who as an employee of a school district is required to report suspected child abuse, also was charged in March with misdemeanor failure to report, court records show.

Bryce Walker’s criminal defense attorney, Shelly Hogan Koehler, said her client is innocent and added, “We look forward to our day in court to be able to prove that.”

Investigators also arrested Barry Walker’s ex-girlfriend and employee, Lori Cogburn.

According to a probable cause affidavit in Cogburn’s case, the 4-year-old girl told investigators in 2014 that Cogburn had “walked in on Barry Walker sexually assaulting her.” Cogburn didn’t report that to authorities and soon allowed another girl to spend nights alone with Walker, the affidavit states.

Cogburn’s attorney, Michael M. Harrison, said in an email that Cogburn “categorically denies” the criminal and civil allegations against her as “baseless and patently false.”

“She had no knowledge of Mr. Walker’s criminal actions with regard to the abused minors,” Harrison’s email said, adding that Cogburn would not have allowed any child “to have been placed in a position of harm by him, or anyone else.”

Bradford’s mother, Joyce Perser, who has not been charged with a crime but is named in the victims’ lawsuit, also didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Perser’s lawyer, Jeffrey Elliott, referred to a motion to dismiss her as a defendant, contending the lawsuit doesn’t provide evidence to support the allegations against her and misplaces blame on Walker’s family members.

“If law enforcement did not foresee the continued behavior of Walker, how can a duty be imposed on Joyce Perser,” the motion states.

‘The most prolific opportunist’

Investigators believe Walker has many more victims beyond the 31 children he admitted to sexually assaulting. He has lived in several other parts of Arkansas and attended military training or resided in at least three other states.

“Barry Walker is going to be the most prolific opportunist as far as any rapist goes in the country when it’s all said and done,” said Jones, adding that a criminal investigation remains “very much open.”

At least six of the victims captured on video have yet to be identified, according to Clark County Prosecuting Attorney Dan Turner . He said several of the victims were sedated when Walker assaulted them and didn’t know they’d been raped until investigators contacted them.

“How do you go tell a 28-year-old that she was raped when she was 12?” Turner asked, when discussing the task that faced investigators. “And, that we know you were raped because we’ve got a video, you just don’t know it because you were unconscious.”

Even though Walker, and Bradford advocating on his behalf, had purported for years that he hadn’t reoffended, evidence shows that Walker didn’t stop raping girls following his initial arrest in Fort Smith in 1999. And he'd offended even earlier, records show. One of Walker’s convictions last year involved a girl whose rape was recorded on VHS cassette in 1997.

Turner — the special prosecutor assigned to oversee all cases related to Walker, including those in Bradford’s district due to her conflicts — told NBC that as far as he can tell, police took the sex abuse claims that cropped up in the years before Walker’s arrest seriously, but “some just couldn’t be shored up with evidence.”

Walker ultimately was convicted of abusing four girls whose claims from 2004 through 2014 were deemed unsubstantiated at the time, based on the videos found last year, Turner said.

Walker was a smart, sophisticated and at times charming manipulator, Jones added.

“He was a flight surgeon who passed medical school and ran several successful businesses,” he said. “No one should underestimate his intelligence.”

After Walker’s arrest, Jones said that Walker told him he was able to pass the private polygraph in 2014 involving the 4-year-old because the examiner “asked the wrong questions.”

Since Walker’s convictions, local press coverage, including a bevy of revelations in a state political blog called the Blue Hog Report, has kept an intense spotlight on Bradford as her hometown has grappled with the scandal.

“A prosecutor is required to report crimes against children,” said Howard “Buddy” Green, who has lived most of his 63 years in Glenwood, a town of 2,200 residents where he says “everyone knows everyone.”

Green speculated that “in my opinion, she was trying to take care of a family member and thought she had enough power to make it happen.”

Green, who said Bradford should be removed from office, is among some locals who said they’ve given statements in recent months to the FBI or state attorney general’s office about Bradford. Others say they’ve separately filed complaints with the Arkansas Judiciary’s Committee on Professional Conduct, contending she filed false and misleading legal records about Walker or inappropriately advocated on his behalf. Neither agency would confirm whether it was investigating.

Bradford’s attorney, who is a member of the state judiciary’s ethics panel, noted “anybody may file a grievance” with the committee. But Bradford has never been disciplined and doesn’t face any pending actions, she said.

“Ms. Bradford has not violated any of her ethical duties, and any insinuation that Ms. Bradford is facing disciplinary action by the ethics committee is false,” she said.

Cassinelli also noted in the email that Bradford has “deep sympathy for Barry Walker’s victims,” and contends that, like others in her community, she was “horrified to learn of (his) depraved acts against children.”

The victim who is now 22 years old said she only learned she was raped last year after reading about Walker’s arrest and contacting an investigator, who told her she was depicted in the cache of videos and photos seized from his home.

The woman now hopes ongoing scrutiny into how Walker became one of Arkansas’ most prolific pedophiles will finally embolden others who kept silent for years to step into the light and hold all of his enablers to account.

“If there’s other girls, I think they need to come forward,” she said. “It’s safe now.”

CORRECTION: (May 13, 2023, 12:57 p.m. ET) A previous version of this article had the wrong middle initial for an attorney. Her name is Michael M. Harrison, not Michael W. Harrison.