YAKIMA, Wash. — Instead of going outside for recess on a recent Friday, fifth-grader Thomas Stevenson walked down a hallway in Ridgeview Elementary School and entered a dimly lit room.

Inside, lavender aromatherapy filled the air, spa-like music played and a projector broadcast clouds onto a screen. Passing by bean bag chairs on the floor and chess sets on tables, Thomas picked up some Legos and began building an elaborate structure.

Thomas, 11, was spending his recess in this converted classroom, known as the Calm Room, by choice. At his previous school, he often got into fights on the playground. His first school suspension was in kindergarten, the year his parents divorced; both parents struggled with drug addiction, and his father was briefly incarcerated.

The troubles at home led to challenges at school. In fourth grade, he was suspended five times.

Since transferring to Ridgeview in the fall, he hasn’t been suspended at all — in part because of the work he has done in the Calm Room.

“People talking about my mom — that’s what I used to get in fights all about,” said Thomas, whose mother has been clean since 2009 and is now a drug and alcohol counselor herself. “It’s nice being a kid that’s not getting into fights anymore.”

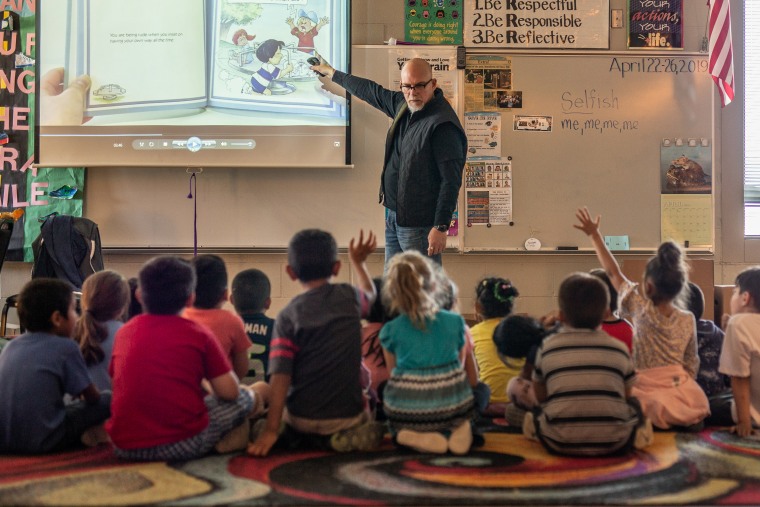

Jeff Clark, a school counselor at Ridgeview, created the Calm Room in January 2018 as a space where students can get help managing heightened emotions, including by talking to an adult, if they want to.

“Some kids want to focus on fixing the problem; some kids just need a safe space to reset,” Clark said.

The room is open to all students, but it is aimed especially at those who are coping with issues at home, such as abuse, neglect or divorce — stressors that are among those classified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs.

Around the country, amid a greater understanding of how childhood trauma affects everything from a youngster’s ability to focus in class to their health as an adult, a growing number of schools are moving away from traditional forms of discipline, such as suspensions or expulsions, and experimenting with new ways of addressing behavior issues. These include encouraging educators to consider why students are acting out; creating spaces where students can do yoga or play with sensory toys, like stress balls or glitter-filled bottles, to calm down; and implementing positive reinforcement systems, such as offering rewards like ice cream for good behavior.

In Yakima, in addition to the Calm Room at Ridgeview, the school district also holds anger management classes, and students who stay out of trouble can get prizes, like a special lunch. While the approaches differ by district, the goal is the same: empower students to process anger and other emotions in a constructive way, and also give them a chance to form a trusting bond with an adult.

“It’s not like the teacher is going to become the mother that the child lost, or whatever happened,” said Susan Cole, director of the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, a joint program of Harvard Law School and Massachusetts Advocates for Children, a children’s rights organization. “But they're going to show them that you can have a good relationship with an adult, that an adult will help you to be successful and you’ll go on to form more caring relationships."

Addressing America’s ‘greatest unrecognized public health crisis’

Psychologists began to understand the far-reaching effects of childhood adversity two decades ago, when a landmark 1998 study by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente found that adverse childhood experiences were linked to a higher risk of health problems later in life, including hepatitis, lung cancer and suicide attempts.

The study found that adverse childhood experiences are common — at least two-thirds of the adults surveyed had one or more ACEs, and nearly one in eight people had four or more.

Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician who was appointed California’s first surgeon general in January, sees childhood adversity as America’s “greatest unrecognized public health crisis.” Starting in 2020, California will screen all children and adults on Medicaid for ACEs, with the goal of helping those who are struggling.

“I think the likelihood that we would eliminate all adverse childhood experiences is similar to our likelihood that we would eliminate all bacteria,” Burke Harris said. “It’s probably not going to happen, and therefore, we need to get much better in treating the effect of adverse childhood experiences.”

Pediatricians can screen for ACEs, but schools can also play a profound role if they train their staff to be sensitive to students’ trauma. Burke Harris, a proponent of teaching children about mindfulness and relaxation techniques, says she believes schools should move away from exclusionary disciplinary policies, like expulsions.

Jamie Howard, a clinical psychologist at the Anxiety Disorders Center at the Child Mind Institute in New York City and the director of the center's Trauma and Resilience Service, said that educating teachers about signs of trauma can help them see students' behavior through a different lens.

“Kids that may seem like they have ADHD because they’re really spacey may actually be distracted by the trauma that’s happened. And then kids who are avoidant of certain things or who have an exaggerated startle response might look oppositional,” she said. “We’ve had kids who refuse to go to the front of the room and write on the whiteboard because they’re afraid to have their back to something they think is dangerous.”

“Something we always say to teachers is instead of saying, ‘What’s wrong with this kid? He’s so difficult,’ try to think what happened to him to make him like that,” she continued. “That can help you come up with a new strategy,” such as working with the child one-on-one or encouraging the child to take breaks so he or she is not overstimulated.

Evidence of success

Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, Washington, is believed to be the first high public school in the country to start incorporating trauma-informed practices in 2010, according to Jim Sporleder, who was then the school’s principal. At the time, students who had been kicked out of other programs were sent to Lincoln, which, at 220 students, was overrun by gangs and had “the most out-of-control environment I had ever seen,” Sporleder, who started working there in 2007, said. Emergency expulsions were frequent; the most common reaction to “any authority was usually kind of an ‘eff you,’” Sporleder said.

Sporleder decided to change his approach after hearing a talk at a conference about toxic stress — the effects on a child’s health, learning and behavior that result from their stress response being activated over and over.

“When kids are in that brain state, they psychologically cannot learn or take in new knowledge,” he said. “By the time I left that conference room, I was on a mission to find out how to change my ways.”

Sporleder told faculty that they had to realize that when students acted out, the behavior wasn’t necessarily in response to the teachers; it could be in response to something else going on in their lives. When Sporleder returned from the conference, a teacher sent a student to him who had talked back. Instead of imposing the usual three-day suspension, Sporleder asked the boy what was going on. To Sporleder’s surprise, the teen opened up about a recent disappointment at home: On his 16th birthday, his father, an alcoholic who had let him down repeatedly, had not given him a car he had long promised.

“He comes down to a safe space and says: ‘The teacher didn’t deserve that. I should go apologize,’” Sporleder said. “The powerful part about this story is, it was not unique. It became the norm. I started asking kids, and my goodness, they started talking.”

Sporleder encouraged teachers at the school to have the same discussions with their students, focusing on forming relationships before automatically sending them to his office. It worked: Referrals to the principal’s office fell to 320 from 600 in a year. Several years later, a case study conducted on the school found that the approach had increased resilience in 70 percent of students, based on their responses to a questionnaire.

Their grades also went up. Those who showed the most gains in resilience had the largest improvements in reading performance and standardized math exams compared to their eighth grade scores, before they had entered the school.

The school and its success were featured in a documentary, “Paper Tigers,” that is often a part of training in other schools.

There is no data on how many U.S. schools have started using this philosophy, though experts say interest in it is growing. The Creating Trauma-Sensitive Schools Conference, led by the nonprofit Attachment and Trauma Network, Inc., grew from 550 attendees in 2018 to 1,200 in 2019, with every state represented at this year’s gathering. Cole’s group, the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, emails guidance on helping traumatized children learn to more than 35,000 teachers and parents across the country and as far away as Pakistan.

‘It feels really good that my mom’s proud of me’

Thomas, the 11-year-old student in Yakima, has learned coping skills from Clark, his school counselor, including taking deep breaths to calm his emotions when he feels out of control. His mother, Breanne Smith, says Thomas’ transformation can be credited to the work he has done in the Calm Room as well as to a behavioral health program that he is eligible for through Medicaid.

Not only is he less aggressive — Smith said Thomas used to kick holes in the walls at home when he lost his temper — but his grades have improved drastically. His favorite subjects are now math and science.

“His change has been just so amazing,” Smith said. “He's always had this potential, and I think he just needed people to see it in him and help bring it out.”

Clark has built Thomas’ confidence by giving him leadership roles, such as being a hall monitor and a “big brother” to students in lower grades who are struggling to listen to their teachers.

In recent weeks, Thomas has trusted himself to spend recess outside with his classmates, venturing out to the playground. Instead of feeling like a bad kid, he sees himself in a new light.

“It feels really good that my mom's proud of me, my dad's proud of me, everybody's proud of me because of how much I've changed since I've been at this school,” Thomas said. “It feels really, really good to not get in trouble.”

Marshall Crook reported from Yakima, Washington, and Elizabeth Chuck from New York.