ALAMEDA, Calif. — As California's record wildfires approached 4 million acres earlier this month, the state's top fire official compared the serial conflagrations to a pivotal event in American history — "The Big Burn" of 1910.

The century-old blaze, which tore through millions of acres in the West, transformed American wildland firefighting into the profession it is today: a force that responds to blazes with mass mobilizations of air tankers, bulldozers and "troops," as the firefighters are often called.

The official, Thom Porter, director of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, suggested that 2020 could mark another turning point.

"The science that was developed to do all those things at that point in time and carried forward 100 years — it didn't do the right thing," he said. "It didn't do the thing we needed it to do right now."

"Every acre of California can and will burn someday," he added. "We need to embrace that and become resilient to it."

Wildland fire experts have been pushing California to change some of those practices for years, but in interviews, they were skeptical that the massive fires and the smoke-choked skies of 2020 will prove to be as pivotal as 1910.

"Maybe this historic event along the whole West Coast will make us hit the reset button," said Timothy Ingalsbee, a former wildland firefighter-turned-fire ecologist who is executive director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology. "Instead of throwing more blood and treasure at this endless, escalating and unwinnable war on wildfire, we shift the paradigm and stake out a new relationship with fire on the land."

"Coming from Cal Fire," he added, "I'll believe it when I see it."

The Big Burn

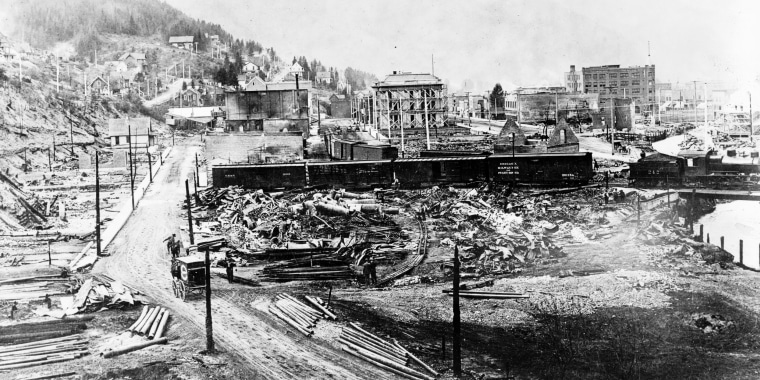

The series of fires that exploded across parts of British Columbia, eastern Washington, Idaho and Montana in August 1910 scorched 3.25 million acres over two days. Eighty-five people died, 78 of them firefighters.

Before 1910, wildfires were treated as a community issue. Most of the time, they were ignored or welcomed as a way to clear land for farming and herding, said Stephen Pyne, a professor emeritus of environmental history at Arizona State University and author of "Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910."

When a wildfire did tear through a community — some of them killed hundreds of people — the response was almost entirely community-driven, Pyne said. They "had to fend for themselves," he said.

The fire of 1910 changed that. It wasn't the biggest or the deadliest wildfire in the United States at that point. But a young federal agency, the U.S. Forest Service, had seen its political fortunes rise just five years before when it took control of the country's vast forestlands, Pyne said, and the fire traumatized the agency. It responded with a set of practices that reflected the progressive, conservation-minded politics of the day, he said.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and alerts

The new philosophy was crystallized in an essay written by the Harvard University philosopher and psychologist William James, who had become alarmed at the U.S.'s escalating militarism.

"He wanted to redirect that enthusiasm" toward "a common foe — the forces of nature," Pyne said.

What followed was the large-scale hiring of firefighters, emergency funding to pay for them and state and federal cooperation to build out the infrastructure to fight fires. Even the symbol of wildland firefighting — a combination ax and hoe known as the Pulaski Tool — was invented by a 1910 veteran, Edward Pulaski, Pyne said.

Another consequential practice of the era — the "10 a.m. rule" — also came from a 1910 veteran. The policy, which lasted for a few dozen fires, according to Pyne, required Forest Service firefighters to extinguish a blaze by 10 o'clock the morning after it ignited.

An 'imperial model'

The policies amounted to an "imperial model," Ingalsbee said. Instead of using fire as generations of indigenous Californians before them had — and targeting vegetation that most rapidly spread it, like dead needles and tree limbs — newly emboldened forestry officials sought "state-dominated control over the environment," he said.

In a memo published in August by the Forest Service and the state of California, the results of that strategy of "wholesale fire suppression" are described as having deprived California's wildlands of a "preferred management tool" — low-intensity fire.

That helped create the overly dense landscape that dominates the state today, one that gave rise to powerful, seemingly unstoppable "megafires," which burn over 100,000 acres. This year, the state has recorded its first million-acre wildfire in modern history, the August Complex, which has been burning across seven counties in Northern California since mid-August.

"Compounding risks have made it nearly impossible for nature to self-correct," the memo says. "A cycle of catastrophic wildfires, longer fire seasons, severe drought, intense wind, tree mortality, invasive species, and human population pressure threaten to convert conifer forests to shrublands and shrublands to invasive grasses."

Gov. Gavin Newsom has described the memo — which includes a joint agreement on catastrophic wildfire prevention — as a "significant milestone" in the effort to prevent such fires: It calls for a million acres a year in vegetation "treatments," like controlled, low-intensity burns, forest thinning and timber harvesting, beginning in 2025. He has also pointed to a separate initiative completed this year that would help protect 200 vulnerable communities from out-of-control fires.

The initiative, prompted by an emergency proclamation after a series of lethal blazes — including the deadliest in state history, the 2018 Camp Fire — totaled 90,000 acres.

Even though that is three times the acreage Cal Fire typically averages in annual controlled fires, Ingalsbee called it "hobby burning." He pointed out that a couple of hundred years ago, before white settlers killed most of the state's indigenous population and miners transformed the landscape, at least 4 million acres would burn annually.

Ingalsbee said Porter's comments and the language in the joint agreement were steps in the right direction. But he was skeptical that Cal Fire wasn't still a "20th century fire suppression machine in the face of a 21st century climate crisis."

Instead of focusing on fires that threaten communities, Ingalsbee said the agency seems to attack every fire, regardless of where it is. He said that in one section of the August Complex fire, for instance, Cal Fire deployed nearly two dozen bulldozers and 10 masticators, or machines that chew through brush and small trees. The blaze would have burned into unpopulated wildlands, and "it would have done a lot of good," he said.

"It would have been a fuel treatment," he said. "But they just threw everything at it to stop the fire from going into the wilderness, which is mind-blowing."

He 'didn't want fire in his forest'

In an interview, Porter acknowledged that suppression has long been one of Cal Fire's primary missions. So has protecting the private landowners who own 40 percent of California's forestland. (The state owns 3 percent; the rest is owned by the federal government.)

"When wildfires start, there are landowners that are going to be affected by that fire," Porter said. "We don't have the luxury of contacting them and negotiating with them. Do they want it put out? The mission is put it out."

That was the case with the nearly two dozen bulldozers used in the August Complex, he said. The agency dispatched all that heavy machinery because the land the fire would have burned through before it reached the wilderness was owned by a timber company. And the timber company's owner believed the fire would have destroyed much of his business.

"We were working on behalf of our constituents, a citizen of California who didn't want fire in his forest," Porter said.

In general, that is what happens, Porter said: Private landowners don't want fire on their land. For those who do, Cal Fire will work with them to ignite "good, healthy fire" — a practice that will expand next year with a new program to train and certify "burn bosses," as private wildfire practitioners are known.

Still, that most of the state's private landowners don't want fire on their land points to a deeper philosophical problem — a problem that will likely determine whether 2020 is like 1910: How do you convince a large segment of a state in which all-out suppression has been the norm for decades that it's at an inflection point?

Pyne, the environmental historian, wasn't convinced that anything will change. The pandemic, the political scene, hurricanes — there are too many distractions, he said. Besides, many thought something significant would happen after 2017, when the deadly Tubbs Fire scorched wine country, he said. The year after that, the Camp Fire exploded across Butte County.

Pyne said that almost immediately after the fire of 1910, the event had been crystallized with a dramatic name — "the Big Blowup or the Big Burn."

"We don't even have a name for these yet," he said. "We don't have the engagement we need yet."

Max Moritz, a cooperative extension wildfire specialist at the University of California, Santa Barbara's Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, said that following "Black Saturday," a deadly bushfire that raged across Australia in 2009, a yearlong inquiry yielded sweeping changes in everything from land use to evacuations and urban planning.

"They went through an enlightenment," he said. "We could hope something like that happens here, where we go beyond talking about fire as a problem of fuels and management."

Porter, meanwhile, is convinced that 2020 will turn out to be a watershed moment. He isn't sure how exactly it will play out, he said, because at the moment he and his firefighters are just trying to get through a season that could drag on for several more weeks.

But looking decades out, he said, he hopes to see a California that can live with wildfire — a state where wind-driven flames don't destroy communities and tear through office tower-size trees.

"It's a fire that can pass through like the rising and falling of the tide, and everything is left on the landscape unscathed," he said.