DURHAM, N.C. — Sequena Pettiford knew something wasn’t right last week with Keyra, her 12-year-old daughter.

Keyra had a bad headache that wouldn’t go away. She had no appetite and felt so dizzy that her older brother had to walk her to her bedroom. The next morning, Keyra later recalled, “I started getting really cold, and I lay down — I felt like I was going back to sleep, but I wasn’t.”

That’s when her mother really started to worry. A few days earlier, shortly before New Year’s, firefighters and emergency medical responders had gone door to door throughout McDougald Terrace, Durham’s oldest public housing complex, warning residents about the danger of carbon monoxide poisoning. Local officials were concerned after receiving several emergency calls involving residents exposed to the toxic gas, including a 1-year-old who was hospitalized before Christmas and later released.

At the emergency room, doctors determined that Keyra had an elevated level of carbon monoxide in her blood, as well as a respiratory infection, medical records show.

She burst into tears, thinking of her neighbors who had also been exposed and fearing the worst. “I don’t want to die,” Keyra said.

The dangerous situation at McDougald Terrace — where first responders have identified at least 15 people other than Keyra with elevated carbon monoxide levels since November — has alarmed public health advocates and lawmakers who have been pushing the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to require carbon monoxide detectors in public housing.

An NBC News investigation last year revealed that at least 13 public housing residents had died from carbon monoxide poisoning since 2003. Months later, the House passed a $300 million bill that would require CO detectors in all federally subsidized housing and fund their installation. But the Senate failed to pass a similar bill, despite a bipartisan effort to advance the legislation in December’s budget deal, leaving vulnerable residents unprotected.

The Trump administration separately announced plans to require CO detectors through the lengthy federal rulemaking process in the wake of NBC News’s reporting, and provided $5 million to install detectors in public housing, but HUD Secretary Ben Carson said last year it would be quicker for Congress to pass legislation.

Without carbon monoxide detectors, the only way to detect the colorless, odorless gas — which at high levels can kill within minutes — advocates have warned that public housing residents across the country are in jeopardy.

“Every moment of delay exposes residents to grave harm and risks loss of life,” Emily Benfer, a Columbia University law professor and a public health expert, said. She has appealed to senators and their staff to act quickly, but she also faults the administration for not moving forward — nearly a year after two public housing residents died from carbon monoxide poisoning in South Carolina, and two grandparents died from the gas in their federally subsidized home in Michigan.

“In the wake of entirely preventable deaths, HUD's response lacks any modicum of urgency,” Benfer said. “This is a public health crisis in the making.”

HUD did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Failed inspections, growing hazards

At the hospital last week, Pettiford tried to reassure Keyra as doctors placed an oxygen mask on her face. After four hours of treatment, Keyra’s carbon monoxide levels returned to normal, and she soon felt better.

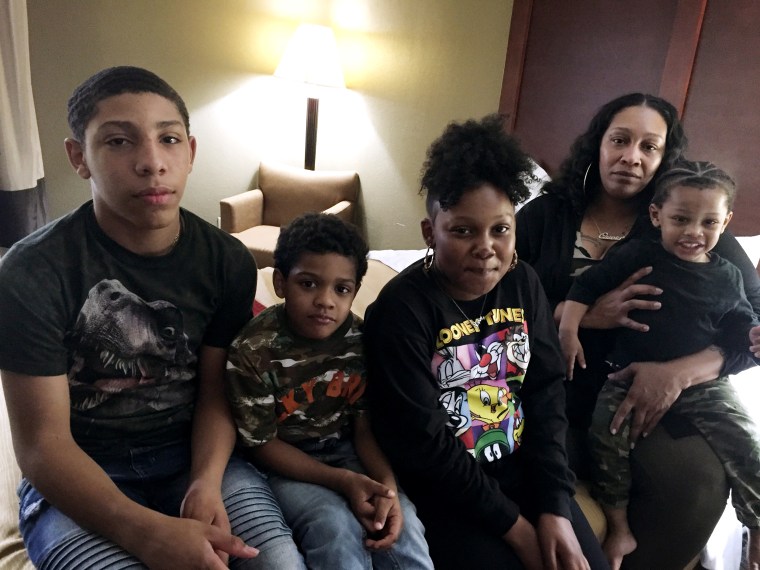

But Pettiford, 35, didn’t want to bring her daughter and three sons — ages 13, 6 and 2 — back to McDougald Terrace, where their furnace had caught fire a year earlier.

“I didn’t know if they were going to sleep and not wake up,” Pettiford said.

Carbon monoxide cases spike in the winter, when residents are more likely to use gas-fired heaters and other appliances that can leak the gas. At McDougald Terrace — a sprawling complex of brick-clad buildings that house 325 families — the antiquated heating system in the units’ living rooms often malfunctioned or belched black smoke, more than a dozen residents said in interviews.

The residents recently found with elevated levels of carbon monoxide at McDougald Terrace range from a 2-week-old who is still being treated at the hospital to a 62-year-old woman, according to Jim Groves, Durham County’s emergency management director. (All the residents survived; two infants at the complex died unexpectedly during the same period, panicking residents, but the state’s medical examiner said Thursday that their deaths were unrelated to the gas.)

The Durham Housing Authority, which owns and manages the federally funded complex, said 84 out of 198 units inspected this week had faulty appliances leaking carbon monoxide. In a recent canvass of the property, fire officials also found a widespread lack of functioning carbon monoxide detectors. More than 270 families who live at the predominantly black housing complex, including the Pettifords, have been evacuated while the property undergoes repairs.

McDougald Terrace failed its last two HUD inspections, receiving a score of 31 out of 100 in March 2019 and a score of 21 in 2017, according to federal records. (A score of 60 or higher is required to pass.) The HUD inspection report from 2019, provided by the housing authority, describes missing smoke detectors, inadequate ventilation for gas and water heaters, and exposed wires, among other life-threatening hazards. The report estimated that the property had more than 1,800 health and safety violations in total.

HUD’s health and safety inspection of the complex wouldn’t have required a check for carbon monoxide detectors, since they are not mandatory in the federally subsidized properties that house more than 4.6 million low-income families. While some states, like North Carolina, require carbon monoxide detectors in certain residences, enforcement is usually left to local governments that have limited resources for inspections. In Durham, for instance, residential properties are not subject to housing inspections on a regular basis, city officials said.

In most places, the only routine oversight of public housing conditions comes from the federal government, which requires all properties to be “decent, safe, and sanitary.”

“HUD should have known — if y’all are doing annual inspections, shouldn’t that have been a flag to you?” Ashley Canady, president of the McDougald Terrace resident council, said. Noting the federal funding of public housing, she added, “If you’re giving somebody money, y’all should be all over this stuff.”

Rep. David Price, D-N.C., whose district borders McDougald Terrace, believes there is an urgent need for HUD to protect residents from carbon monoxide hazards and address the widespread disrepair in aging properties. He is pressing the Trump administration to move forward with a rule requiring carbon monoxide detectors in public housing.

“HUD is the agency that, at the end of the day, has responsibility for the national standards,” Price said. “Carson announced his intention to make this a requirement — but this was months ago.”

The lack of federal protections has endangered some of the country’s poorest and most vulnerable families, advocates say — especially since young children and the elderly are more susceptible to carbon monoxide poisoning. Residents of old buildings like McDougald Terrace are particularly at risk, as their homes are more likely to have outmoded appliances and inadequate ventilation. More than 500 children live at the complex, the Durham Housing Authority said.

“We are in the middle of winter and there is no time to waste,” Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., who co-sponsored a bill to require detectors in federally subsidized housing, said in a statement. “Every day that goes by without passing our bipartisan CO ALERTS Act is a day families’ health and lives are put at risk by exposure to carbon monoxide poisoning while living in public housing.”

‘They just didn’t care’

Sequena Pettiford says she was afraid even to turn on the heat at McDougald Terrace, where she moved in the fall of 2018 after being laid off from her cleaning job at a local hospital. That winter, the furnace in her living room caught fire, setting her couch aflame, she said. The replacement heater was smoky and immediately burned red-hot; Pettiford said that when she asked for a new one, the staff replied that they were back-ordered, but one never arrived. (The housing authority said it did not immediately have information about the incident.)

So as it got colder this winter, she turned on the oven to heat up her home, as did many of her neighbors. “What else was there to do?” she said. Pettiford had never had a gas stove in her home before and didn’t realize it was hazardous to use as a heater. And there were no carbon monoxide detectors in her home, she said.

After a wave of CO-related calls at McDougald Terrace in late November and December, local officials deployed an emergency response team to the housing complex shortly after Christmas. Going door to door, the first responders warned Pettiford and the other residents against using ovens for heat, explaining that they could be another dangerous source of carbon monoxide. They also tested her 2-year-old son and found that he had an elevated level of carbon monoxide, which subsided by the time she brought him to the hospital, Pettiford said.

Fire officials found missing or malfunctioning carbon monoxide detectors across the complex, according to Durham Fire Chief Robert Zoldos. The team has installed or replaced a total of 228 detectors, the housing authority said.

After the fire department’s visit, the property management gave Pettiford box heaters to use temporarily, but the power went out when she plugged them in, she said. So she shut off the oven and went without heat. It was a few days later that her daughter was rushed to the hospital with a high level of carbon monoxide in her blood. The new detector never sounded, she said; Pettiford doesn’t know exactly when or how Keyra was exposed.

Pettiford now worries about the long-term health impacts of carbon monoxide on her children, especially on their brain development: “It’s exposure to poison.”

Carbon monoxide exposure has been linked to cognitive impairment, heart problems and memory loss, among other serious health issues, Dr. Jason Rose, a medical professor at the University of Pittsburgh, said. “Your brain is not getting enough oxygen,” he said. “I think about it as a traumatic brain injury — it can have a really devastating impact.”

Anthony Scott, CEO of the Durham Housing Authority, said that carbon monoxide detectors should have been placed in every unit and checked as part of the management’s own internal inspections. But, Scott said, he did not know whether his team had actually checked for detectors, or if they were all installed and functioning before the recent carbon monoxide incidents.

In Pettiford’s home, the housing authority noted a missing smoke detector and a roach infestation in 2018, according to the housing authority’s internal inspection report that she provided to NBC News. But the housing authority's own inspection form makes no mention of carbon monoxide detectors.

Scott acknowledged missteps by the housing authority and said he was taking steps to ensure the units are “safe and habitable” across McDougald Terrace. “Residents are saying, ‘we’ve reported an issue, and it hasn’t been resolved.’ Neither one of those things is acceptable,” he told NBC News.

But Scott also blamed a lack of federal funding for public housing. A 2010 study estimated that the national backlog of capital repairs in public housing is $26 billion, growing by $3.4 billion each year. “We have a very old property that ultimately needs to be redeveloped,” Scott said, noting that the complex had been built in 1953. A few months ago, a sewer line collapsed on the property, spilling raw sewage that young children were exposed to, residents said.

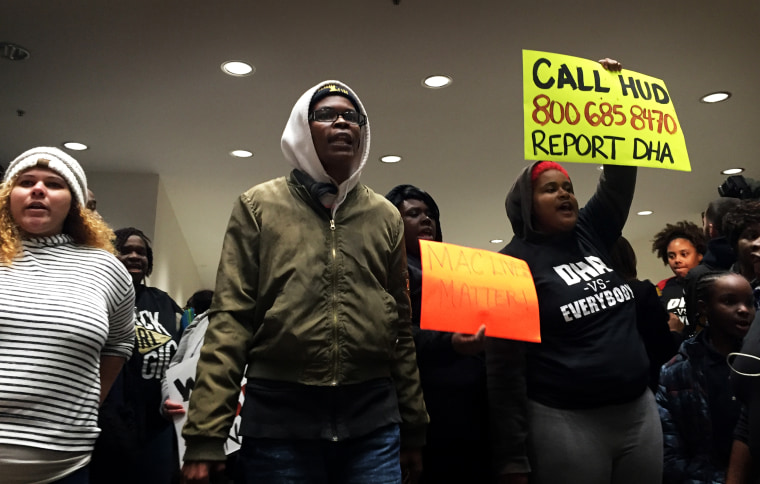

The carbon monoxide leaks and other hazardous conditions at McDougald Terrace are now spurring widespread outrage in Durham as the story has spread on local news and residents, along with community activists, have mobilized on Facebook.

“They just didn’t care,” said Shontara Clemmons, a resident with a 3-year-old son. “They didn’t care until it was all out in the open, where it’s in the news, and now everybody cares.”

‘You’re not safe’

More than a week after being evacuated, hundreds of residents are still huddled in hotel rooms throughout the Durham area, subsisting on donations and food vouchers, and scrambling to get their children to school across the city. The housing authority continues to conduct inspections and repairs and does not know when residents will be able to return home.

On Monday, more than 150 residents and community members packed a Durham City Council meeting, testifying for nearly three hours.

Samather Crowder brought her 6-month-old daughter up to the microphone: “Have you ever had to look in your baby’s eyes and fear death because of the conditions of your living situation?” she asked.

Another resident stepped up to describe the fear and desperation she felt trying to keep her two young children safe. “We’ve got to come up here and beg y’all for help,” she told city officials. “It shouldn’t be us begging — we’re not dogs.”

Pettiford doesn’t trust that McDougald Terrace will be safe, even after the repairs are finished. She kept her children inside when they lived there because of all the violence in the neighborhood. This past October, she was carjacked. In late November, a young man was shot outside her building; she and her 13-year-old son watched him die as the ambulance arrived.

“You can’t play outside,” she said. “And you’re not safe inside.”