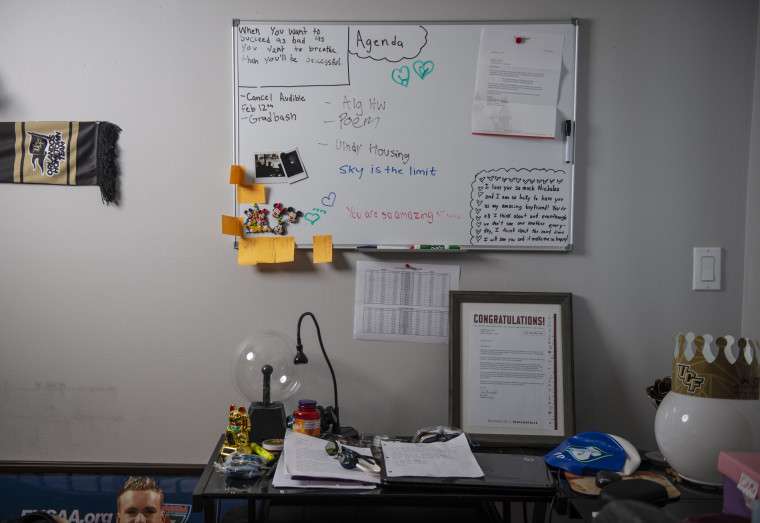

The first reminder of all the things Nicholas Dworet would miss was on a whiteboard in his room, where he wrote his goals and inspirational quotes.

“It had things like ‘grad bash'...written on it,” Mitch Dworet, Nick’s father, said. “It started at prom, which was very difficult. Then we got his graduation pictures.”

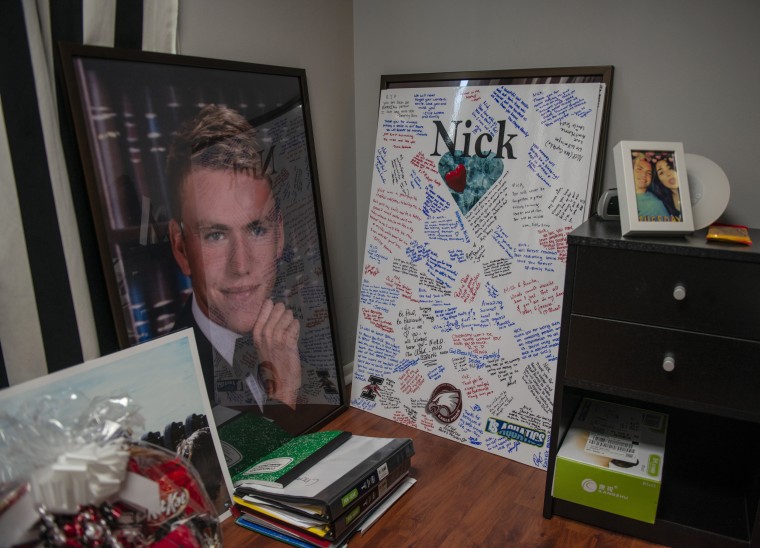

Nick, a swimmer with aspirations of Olympic gold and an infectious smile, was among four seniors killed when a gunman opened fire at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, on Feb. 14, leaving 17 students and teachers dead.

His parents are now coping with the final high school milestone their son won’t get to experience: graduation.

Watch “Voices of Parkland: Healing Out Loud” premiering on Sunday at 10 p.m. ET on MSNBC

At the school’s commencement ceremony at the BB&T Center in Sunrise, Florida, on Sunday — the final day of "Wear Orange Weekend," an awareness campaign organized by gun violence prevention advocates — Dworet and the other three seniors killed in the shooting will be remembered, along with two others in the class who died before this year, one of illness and the other by suicide.

The school has not released plans for how the six students will be memorialized, but the Dworets said some of their son’s swimming teammates and friends, many of whom he mentored, will be wearing his name on their graduation caps.

The four seniors killed on Valentine’s Day had begun planning for life after high school: Nick Dworet had earned a full swimming scholarship to the University of Indianapolis; Meadow Pollack was headed to Lynn University in Boca Raton; Carmen Schentrup had been accepted to the University of Washington, with hopes of becoming a medical researcher; and Joaquin “Guac” Oliver hadn’t decided on a college yet, but was considering studying marketing and moving to Orlando.

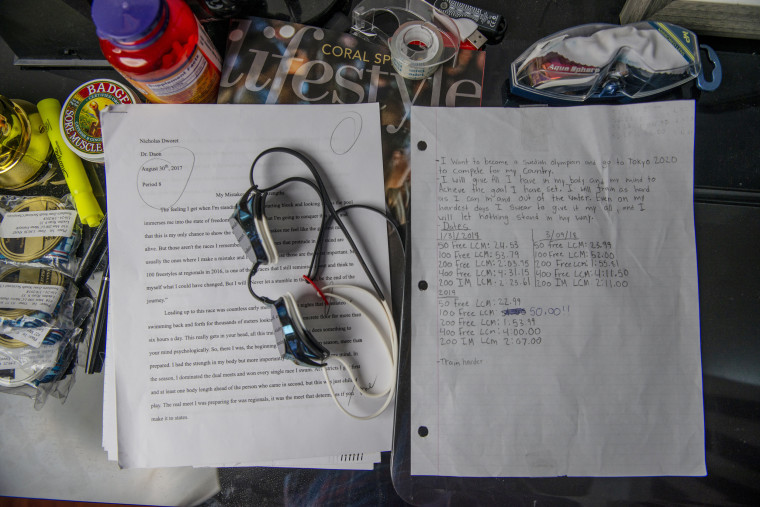

“He was on his way,” Annika Dworet, Nick’s mother, said. “That’s the thing about getting cut short. Nick was right there. He was ready to go to the next level. One week before the tragedy, he had signed with the University of Indianapolis.”

To Parkland’s surviving seniors, memories of their lost classmates can’t help but turn what should be a celebratory moment into something more somber.

"It kind of hurts to graduate because you’re graduating and everyone is supposed to be in on this together, and now you don’t have four people that are supposed to be with you," said Amanda Edwards-Berlingeri, 18, who was a close friend of Schentrup.

Schentrup pushed herself in high school, believing she’d have time for fun once she was in college, said Anisha Saripalli, a fellow senior.

“I wish Carmen was here,” Saripalli said. “She worked way harder than I did.”

The families of all four seniors have created scholarships and nonprofits in their children’s names. The Pollacks formed Meadow’s Movement, which works to build a memorial playground in South Florida. Schentrup’s family started the Carmen Schentrup ALS Fund, to battle the disease the 16-year-old hoped to one day research and cure. Oliver’s family began Change the Ref, an organization that aims to educate American youth about ways to change the future of government and politics.

And the Dworets created Swim4Nick, which offers scholarships to swimmers, an attempt by the family to give back to the organizations that helped their son hone his skills.

In the last year of his life, Nick spent hours each week swimming. He hoped to one day compete in the Olympics for Sweden, where he also had citizenship. When he wasn’t swimming, he was talking about Adidas or Supreme brand clothing or texting with his girlfriend.

Annika Dworet was at a Walmart near Stoneman Douglas on the day of the shooting. As she left, she saw helicopters and police surrounding the school and heard rumors that a shooter was on campus.

She soon learned her younger son, Alexander, 15, had been grazed by a bullet. As she raced to a Broward County hospital to be with him, she and her husband frantically tried to get in touch with Nick.

“There are 3,400 kids at the school, and what’s the odds of two of mine being shot?” Annika said she thought at the time. “Nick must be OK. I’m going to take care of Alex.”

Mitch Dworet said his fears began to rise as he and other distraught parents waited at a nearby Marriott that night for information about their children. It wasn’t until the early hours of the following morning that they learned Nick had been killed.

“It was a torturous night,” Mitch Dworet said. “It was hell. We were both in shock.”

For some of the families of the Parkland victims, the prospect of attending graduation is too overwhelming. Some said they will try to forget the day is even happening.

At first, the Dworets considered doing the same.

But as the date grew closer, the school reached out and offered them a private area to watch the ceremony and told them they could send someone to walk across the stage for Nick and collect his diploma.

“They asked if we wanted a representative from our family to walk up or not,” Mitch Dworet said. “At first we thought, ‘We can’t do it.’”

Then the Dworets approached Alexandra Greenwald, 17, a classmate of Nick’s who had been his friend since kindergarten.

“I thought it was a huge honor,” Greenwald said, “and I was really humbled when they asked me to walk across the stage for them.”

Greenwald will attend the University of Iowa on a gymnastics scholarship this fall. As she competes, she said she will draw on memories of her friend’s athletic dedication and perseverance. “We literally walked into kindergarten together,” Greenwald said. “It was almost a given we’d graduate together, and now that he can’t, it means so much to me to be able to carry his legacy on and help him and his parents.”

The Dworets said they probably won’t stay for the entire ceremony — witnessing another milestone Nick is missing may be too much.

“It’s easy to talk about the good memories with Nick,” Annika Dworet said, “but it’s very difficult to talk about the things he’s not going to get to do.”