Long before a global pandemic swept across her cloistered corner of the Navajo Nation, Cynthia Wilson knew the pains many families took to secure and store food.

The multigenerational home she shares with her parents and eight others in Monument Valley, Utah, runs on solar panels and a generator. With no running water, her father hauls it in almost daily. They live about 8 miles from the closest and only grocery store in their high desert community, where shoppers have felt the strain of limited supplies through the rationing of foods like meat.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic "people were dependent on the grocery store," Wilson said. "Now, they're in shock or worried about how they're going to keep their pantries filled when they can't go to the stores like they used to. It's a wake-up call that we need to go back to growing our own foods and tending to our own livestock."

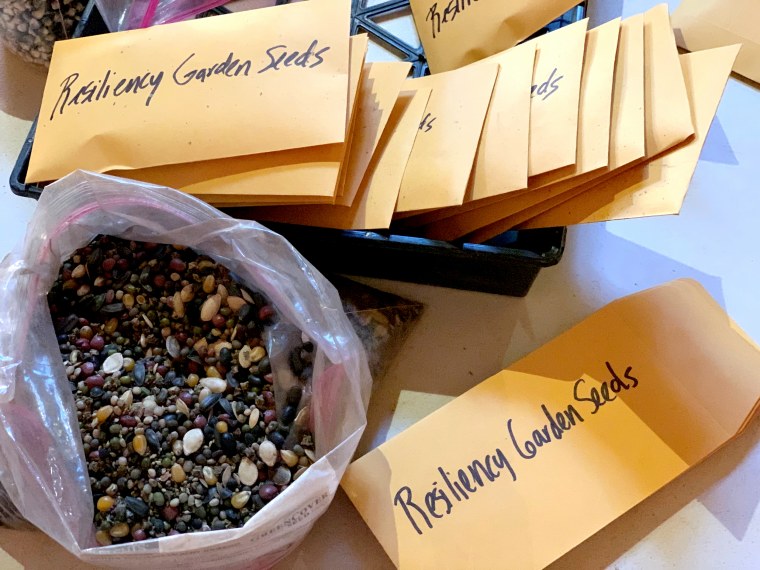

Wilson, the traditional foods program director of Utah Diné Bikéyah, an Indigenous-led nonprofit that has worked to protect the Bears Ears national monument in southern Utah and the ancestral lands of several Indigenous peoples, found her motivation amid all of the uncertainty. This month, she helped launch a "Seeds and Sheep" program in response to the pandemic and mailed out 1,500 seed packets to homes in the Four Corners region that want to plant and grow their own food.

The initial goal was to reach 100 families. She heard from more than 300.

Across the country, as households turn to planting and gardening as a relaxing hobby or to become more self-sufficient during turbulent times, the act of cultivating one's own food has taken on a greater significance among Native American communities where the pandemic has laid bare an enduring food crisis and a desire to return to customs and traditions some fear are slowly being lost.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

The idea of Native food sovereignty — that tribes can farm, access and secure healthy and culturally essential foods that empower their citizens, respect the lands and are not bound to outside policies — was already a growing movement among Indigenous peoples, said Elizabeth Hoover, an author and assistant professor of American studies at Brown University who writes about food and environmental health and justice in Native communities.

But for more people to move toward food sovereignty, "a lot of elders would say what it's going to take is a crisis that will keep people from going to the grocery store and picking up food like they used to," she said.

Seeding a movement

Hoover, who is of Mi'kmaq and Mohawk ancestry, grew up on a farm in upstate New York. Elders of the Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne, whom she had interviewed for her first book, told her that "nobody knew the Depression was happening around here because everyone had their own gardens."

Despite untrue assumptions that Native American tribes have a multitude of acres at their disposal and primed for harvesting, outdated policies and discriminatory lending practices by the federal government have kept many Native farmers at a financial disadvantage, Hoover said.

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reached a $680 million settlement on a class-action lawsuit that alleged the agency engaged in discriminatory lending against Native American farmers for nearly two decades. Those farmers said they received significantly fewer loans and more onerous terms than were provided to white farmers. In response, the USDA said it is "committed to resolving all cases involving allegations of past discrimination by individuals."

But the troubling legacy of discrimination intersects with other urgent issues surrounding food sovereignty, including disparities in Indian Country of poor health care and disease, now exacerbated by the coronavirus; environmental battles over oil pipelines and access to clean water; federal policies that have eroded tribal territory and ancestral lands; and climate change that has led to increased drought and flooding throughout the country.

With so much at stake, Hoover said, the younger Native American generation is seeing the appeal of a type of farming that's more community-oriented rather than mass farming, like growing soybean and corn for commodities markets, or on the opposite end of the spectrum, a quaint pastime.

"It's not just doing as grandma did: Plant your garden because it's an old-timey thing to do," she said. "It's resistance to corporations, to people working cheek by jowl in meat plants, to an unreliable supply chain where products are shipped from thousands of miles away contributing to the carbon footprint. So for these young folks, they're asking: How do you resist that system and all it stands for?"

Changing mindsets

Attempts to challenge that system to the benefit of Native populations are being made by Cherokee communities swapping seed kits for each season, Oglala Lakota chefs preserving Native food traditions and Native-run community colleges teaching methods that might otherwise be forgotten.

Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College, a public tribal community college in New Town, North Dakota, will begin its "food security" program this week, said Lori Nelson, the school's land grant director. Eighteen applicants have signed up to learn how to grow their own gardens or plant using containers, while the college itself expects to make produce available to people through an acre-size "pick-your-own" garden.

"Much of North Dakota is in a food desert," Nelson, who recently applied for a USDA grant, said. "People are very used to flour and sugar and processed foods. It's really difficult to change mindsets."

Fort Berthold in New Town, the headquarters for the Three Affiliated Tribes, also known as the MHA Nation, has obesity rates of 86 percent among the adult population and 55 percent among school-age children, triggering higher rates of diabetes and heart disease.

Nelson said the hope is to lead citizens down a path with healthier options.

"If you grow your own food," she added, "you're more likely to eat it."

Growing results

Native seed organizations say the pandemic has increased interest in what they've been doing for decades.

The requests for seeds from the Traditional Native American Farmers Association has doubled this year, said Clayton Brascoupe, one of the founders who has farmed in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of New Mexico for more than four decades.

The association, which has shipped its locally sourced seeds to as far away as Canada and Florida, formed in 1992 to help bring more people, especially youth, into agriculture, teaching about seed quality and germination. Brascoupe, of Mohawk ancestry, said the seeds his association stores are not only important because they're indigenous, but they're nutritionally superior to hybrids.

"In years past, someone would write or call us, 'Can you send me two to three packets of seeds?'" Brascoupe said. "This year, we got hit by a lot of requests. It's not just a couple packets — we're sending those large priority mail boxes."

Among those who received donations was the organization Utah Diné Bikéyah, which refers to the "human relationship to the earth's surface" in the Diné Bizaad, or Navajo, language.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Alastair Bitsóí, an organization spokesperson who is Diné and a citizen of the Navajo Nation, said the fact that Native farmers are sharing their resources with the "Seeds and Sheep" program is meaningful.

"It's coming, not from outside sources, but within," he said. "That's the beautiful thing."

The seeds — which include corn, squash, melons and beans — will be ready to harvest for growers by late summer and the fall, depending on the type of variety, Bitsóí said. Indigenous families are being asked to share pictures of the fruits — and vegetables — of their labor.

Since access to running water and reliable infrastructure remain a problem on Navajo Nation lands, families in the program are being provided 275-gallon water tanks if needed.

The program is "a long-term solution," Bitsóí said, in the face of a future wave of COVID-19. The illness has already ravaged the Navajo Nation, which straddles Arizona, New Mexico and Utah and has seen a startling infection rate of more than 2,300 cases per 100,000 people.

This fall, Utah Diné Bikéyah plans to distribute Navajo-Churro sheep to families interested in livestock farming, another way to keep cultural connections alive, which Bitsóí said is needed "more than ever" during the pandemic.

"We want our people to basically stop drinking the milk of the border towns and drink right from the source," he said.

Cynthia Wilson agrees. When she looks out at the rows of reddish-brown soil behind her home in the Monument Valley and watches her father as he dutifully waters the Diné blue corn, the yellow corn and white corn, the Anasazi beans, the Diné cushaw "tail squash" and melons, she is hopeful that others can replicate the bounty for themselves.

The blue corn, she said recently, was already peeking out of the earth.