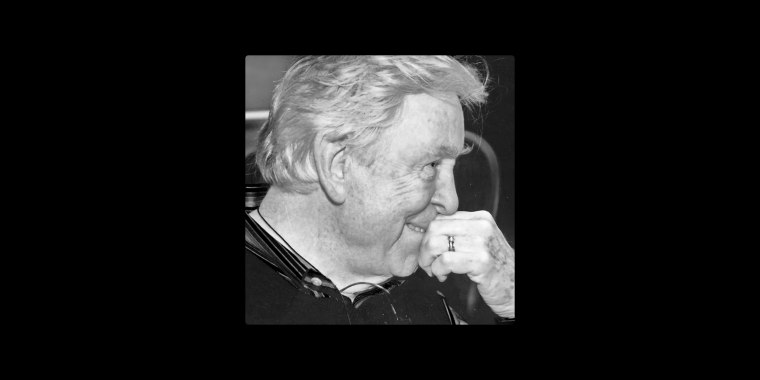

William Pursell could not wait to get back into a recording studio.

The 94-year-old composer and musician spent the first half of the year arranging songs for a new album called “Lilacs,” a collaboration with his daughter Laura, a singer. The album was a blend of original tunes and American standards. Pursell wrote the title track in honor of his wife, Julie, who died in 2018. The father-daughter duo resolved to finish the project as soon as the music industry was back up and running.

Then, in early August, Pursell was hospitalized in Nashville, where he lived and worked for some 60 years. He tested positive for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Pursell, who went by Bill, told his daughter he wanted to fight the virus “tooth and nail” and return to his work as quickly as possible, she said in a phone interview this week.

But on Sept. 3, the Thursday before Labor Day, Pursell died of complications from COVID-related pneumonia.

Pursell was not a household name outside the Nashville arts scene where he was regarded as a folk hero. But over the course of a busy and eclectic career, he built a reputation as an artist of eminent versatility and quiet accomplishment, swinging easily from classical styles to country, jazz and pop. He even composed a "bluegrass opera" about President Andrew Jackson.

Sometimes that work came with recognition: He scored a Top 10 hit with the instrumental song “Our Winter Love” in 1963. He earned two Grammy nominations.

Sometimes it was behind the scenes: He taught composition at Belmont University, mentoring students such as Brad Paisley and Trisha Yearwood. He worked alongside legends, including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and Patsy Cline.

“If you are somebody who didn’t know who he was, you might be surprised to discover how many albums he played on, especially during the 1960s,” said Terry Wait Klefstad, a fellow music professor at Belmont University and the author of “Crooked River City,” a biography of Pursell. “If you pull up an old Columbia Records album and turn it over, there’s Bill Pursell on the keyboards.”

Pursell was born June 9, 1926, in Oakland, California, and raised in Tulare, a town in the state’s Central Valley. He studied composition at the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, and worked on arrangements for the U.S. Air Force Band while serving in World War II, according to his publicist, Harlan Boll.

He then studied classical composition at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, earning a master in composition in the 1950s. (In the early 1990s, Pursell returned to Eastman to complete a doctoral program in the musical arts, the school confirmed in an email, praising his “commitment to lifelong learning.”)

Pursell moved to Nashville in 1960 at the invitation of country music artist Eddy Arnold. Two years later, he signed as a solo artist with Columbia Records, which later released his album “Our Winter Love.” The title song, a mellow piano-and-strings riff accompanied by an angelic chorus, became a mainstay of Christmas radio playlists.

Throughout the 1960s and the 1970s, Pursell worked as a session pianist for some of the biggest names in music. He cherished the night he and country star Chet Atkins played at the White House for President John F. Kennedy. He nabbed Grammy nominations for his work on the album “Listen” for Ken Medema in 1974 and for his arrangement of “We Three Kings” for National Geographic in 1978.

Pursell was seen by family and friends as a keenly intelligent raconteur, beloved for his colorful anecdotes about recording sessions with American greats such as Patsy Cline and Johnny Cash.

“He was gregarious,” Klefstad, the author of his biography, said. “He had a wonderful sense of mischief. He would get this sparkle in his eye when he would tell funny stories. He was a born storyteller, and that’s what made it easy to write a book about him. He could just sit and tell stories for hours.”

Pursell was also a committed progressive who abhorred racial injustice and social inequality.

In the early 1970s, he led a weekly discussion group called the Wednesday Night Club, his daughter said. The group, “a liberal-minded cross-section of Nashville” that included the widely respected Black jazz musician and educator William Oscar (W.O.) “Smitty” Smith, met in the back of Pursell’s house to discuss civil rights issues.

The club’s members’ conversations about unequal access to education helped lead to the founding, in 1984, of the W.O. Smith Music School, according to Klefstad. The school, according to its website, makes "affordable, quality music instruction available to children from low-income families." (All classes and lessons are 50 cents each.)

In his final days, Pursell was intensely focused on the upcoming presidential election, telling his daughter that he was eager to cast his ballot for former Vice President Joe Biden. He also found new spiritual fulfillment: Pursell, who was raised as a Methodist, became a Catholic in Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s COVID-19 ward with the help of a sympathetic priest.

“He called me on Zoom from the hospital and said, ‘You know what, Laura? Finally, my whole life makes sense.’ I was so happy to hear that.”

Laura Pursell said she was moved by the outpouring of grief for her father. She said she learned that the producers of the 55th Academy of Country Music Awards plan to feature him during an In Memoriam segment at their ceremony Sept. 16.

When it is safe to return to a recording studio, Laura Pursell plans to complete “Lilacs,” the album she and her father were working on right up until his hospitalization.

“My intention is to go in and finish it,” she said. “I want to finish his work.”