At 40, Adrian McGonigal had the best job of his career working in the shipping department of Southwest Poultry in Pea Ridge, Arkansas — a town of about 5,700. He’d suffered from a slew of serious medical conditions, but thanks to the state’s decision to expand Medicaid, he was able to go to the doctor and get the prescriptions he needed to continue to work.

But then Arkansas imposed work requirements on Medicaid, which meant that he had to go online to report the hours he worked to the state government. McGonigal — who had limited access to a computer and has trouble using them — didn’t realize he would have to report his hours every month, so when he went to pick up his prescription in October, he was told his medication would cost $800.

He hadn’t fulfilled the work requirement order, so he lost his insurance. Because he couldn't afford his medicine, his health worsened, he missed several days of work due to illness and Southwest Poultry fired him.

That anecdote leads the 35-page opinion that struck down Arkansas’ work requirements law last week, stymieing the legislation that had caused 18,000 Arkansans to lose health insurance over the past several months. About 2,000 were able to re-enroll after losing their coverage.

The state government promoted the law as a way to bolster self-sufficiency in the state’s poorest population, targeting specifically those who received health insurance under the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion.

But a handful of Arkansans said that losing that health insurance cost them their ability to work, and so they sued Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar after the Trump administration provided Arkansas a waiver to apply work requirements to the federal health insurance program.

Kevin de Liban, a Legal Aid of Arkansas staff attorney who worked on the case, said the 10 plaintiffs were relieved “more than anything” by the recent ruling. “But what’s missing in the discussion is how much stress there is and anxiety and fear and worry whether or not you’re going to have the medicine to keep your job and live a full life."

The rulings highlight a debate over the fundamental objective of the healthcare program and comes as Donald Trump revitalized a battle over health care on Capitol Hill this week. Administration officials insist that Medicaid is a welfare program, and so they can provide state’s waivers that allow them to amend the program and add work requirements.

Critics, however, contend that the founding principle of Medicaid is to provide low-income people access to health coverage — a concept reestablished with Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, known as the ACA or Obamacare.

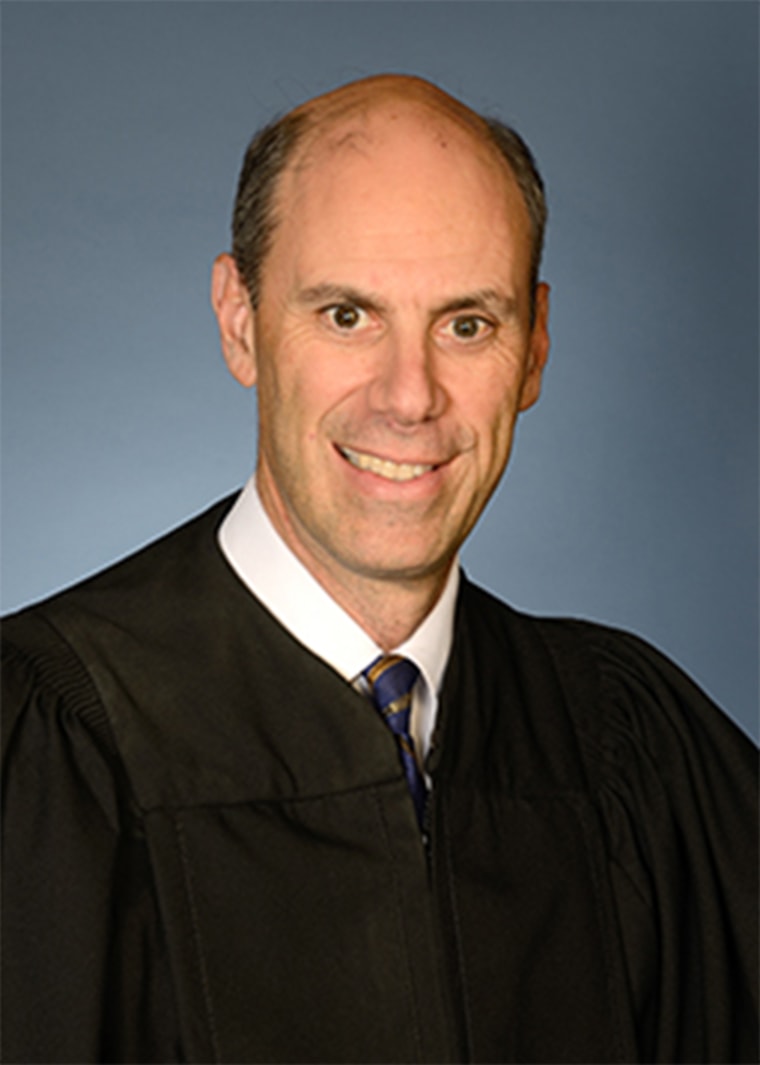

The critics appear to have won that argument this week when Judge James Boasberg of U.S. District for the District of Columbia ruled the Arkansas requirements were "arbitrary and capricious because it did not address — despite receiving substantial comments on the matter — whether and how the project would implicate the 'core' objective of Medicaid: the provision of medical coverage to the needy."

The judge, an Obama appointee, also blocked a parallel waiver in Kentucky, the second such ruling in that case. A third lawsuit from New Hampshire is still pending with Boasberg as well, and advocates are hopeful to get a comparable judgment.

“There’s a similar lack of consideration of what the impact would be on coverage in New Hampshire,” said Sarah Somers, the managing attorney for the National Health Law Program, a group that is working on all three cases.

But on Friday, two days after the rulings came down against the Trump administration-provided waivers, Azar approved a similar waiver for Utah, showing that the ruling had not shaken the Trump administration’s resolve to limit the program and appearing to invite further litigation.

And the table is set for that to occur.

Five other states — Wisconsin, Maine, Michigan, Arizona and Ohio — have also received waivers to implement work requirements from the secretary and six more are awaiting approval: Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee and Virginia.

Work requirements were approved and pushed by the Trump administration’s Department of Health and Human Services and Seema Verma, the administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), a longtime advocate for limiting Obamacare and Medicaid.

“We will continue to defend our efforts to give states greater flexibility to help low income Americans rise out of poverty,” Verma said in a statement in response to the Kentucky and Arkansas ruling. “We believe, as have numerous past Administrations, that states are the laboratories of democracy and we will vigorously support their innovative, state-driven efforts to develop and test reforms that will advance the objectives of the Medicaid program.”

CMS did not respond to a request for further comment.

Experts and critics, however, hope that this will force the Trump administration and state governments to be more transparent about the impact that these policies could have and contend with the realities of a low-income labor market that doesn’t always produce the 80 hours of work needed each month to meet the requirement.

“There’s going to have to be more public discussion of who's going to get dropped off, what’s going to happen to them and what’s the justification for that,” said Andy Schneider, a researcher at Georgetown University and Medicaid expert who worked at CMS during the Obama administration.

What happens next for Arkansas and Kansas remains unclear, but it could have major and immediate implications for thousands of people. More than 16,000 Arkansans who used Medicaid prior to the work requirements are still without it even after the ruling.

Because of the judgment, though, thousands more won’t lose their insurance come April 1 — when the next group of people were slated to be dropped from the program. They’ll still lose coverage, however, if the program is reinstated, and this time it will also include those from the ages of 18 to 29. The law previously only applied to those from 30 to 49.

Meanwhile, despite the setback to the state’s intentions, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, urged the Trump administration on Thursday to appeal the decision so the state could move forward with its plans.

“We don’t know yet what the federal government is going to choose to do with Arkansas and Kentucky,” said Somers, “whether they will remand like the judge suggested or take different path.”

The secondary path and likeliest path, many say, would be an appeal to the D.C. Circuit Court and then the Supreme Court.

“There’s certainly reason to think they might do that,” Somers added.