Michelle Wu, a City Council member in Boston, wants everyone to ride for free on subways and buses that crisscross the region.

Wu says the city is experiencing a "transportation crisis" as ridership declines, rush-hour traffic rises and the infrastructure of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority continues to crumble.

The transportation authority needs salvation and money for repairs, commuters and local transit advocates say, but instead of raising fares beyond the $2.90 it costs now if you pay for a subway ride in cash, Wu thinks a solution may lie in dropping fares altogether.

Her position is shared by other progressive lawmakers across the country who say mobility is a human right, like health care and education, and think residents should be able to freely move around their cities, no matter their income brackets. They propose eliminating fares on city buses, light rail and trains to achieve their vision of universal mobility. But some experts warn that free rides wouldn't solve the issues besetting many public transit systems, including crumbling infrastructure, infrequent and unreliable service, and routes that take workers nowhere near their jobs.

Kansas City, Missouri, could become the first major city to eliminate bus fares in June under a proposal in the budget the City Council is expected to approve by the end of March.

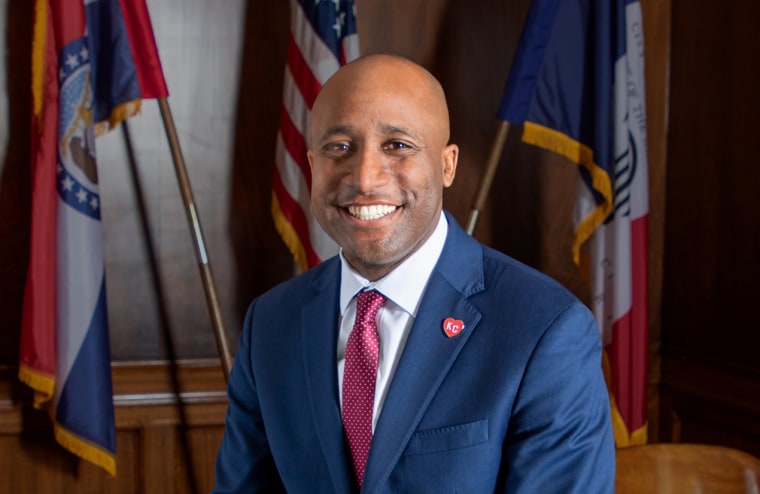

Mayor Quinton Lucas said scrapping the $1.50 bus fare would be a windfall for working-class families that spend a good part of their incomes on transportation, and he believes it would benefit the city's economy, allowing people to move around more easily and patronize local businesses.

"Making transit free makes more job opportunities accessible for more people," Lucas said. "We're a car-based city, so if you don't have a car or bus fare, you don't get to where you need to be."

The city would lose $8 million a year on fare-free transit, but Lucas insisted that it would not be "a significant amount" of Kansas City's $1.7 billion budget. By not paying for maintaining and using a fare collection system, the city would save about $3 million a year, leaving Kansas City officials to come up with only $5 million to cover losses, Lucas said.

He said critics rarely ask where the money comes from for other projects, like the hundreds of millions of dollars spent each year on building and maintaining streets or the $325 million to renovate Arrowhead Stadium, where the Kansas City Chiefs play.

"That costs us and local government tens of millions of dollars a year," he said. "So I think the real question people have to ask is 'Do we care about the public?'"

Robbie Makinen, CEO of the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority, said public transit is the glue that holds a community together.

"The return on investment for social justice, compassion and empathy far outweighs the return on investment for asphalt and concrete," he said.

The Kansas City transit authority partnered with the Center for Economic Information at the University of Missouri-Kansas City to analyze the economic impact of the proposed zero-fare policy. The study found that free transit would increase Kansas City's regional gross domestic product by more than $13 million a year and improve the livelihoods of regular riders along with new riders encouraged to try public transit without the fare barrier.

"For those living paycheck to paycheck, as most Americans are, even an additional $50 (the cost of a monthly bus pass) per month of income can make the difference in deciding which bills to pay," the study said.

Kansas City has embarked on similar but smaller experiments before. In 2017, it made transit free for veterans and the next year for ninth- to 12th-graders in four major school districts.

While advocates have championed the move, they say fare-free policies aren't enough if transit isn't accessible.

Comparing 100 metropolitan areas of similar size to Kansas City, a 2011 report from the Brookings Institution found that Kansas City's transit system was among the 10 worst at connecting workers to their jobs, with only 18 percent of jobs in the metropolitan region accessible to job seekers by commutes of less than 90 minutes.

For that reason, city leaders should not look at eliminating fares as a "panacea" for transit problems, said Hayley Richardson, a spokeswoman for TransitCenter, a nonprofit group based in New York City that works to improve public transit around the country.

"A bus that comes once an hour that's free isn't useful to people," Richardson said. "The way we make transit useful to people is by making it come frequently and reliable."

Instead of eliminating fares, Richardson said, cities need to prioritize creating transit systems that actually serve their customers. The best scenario would be cities where buses arrive every five minutes in dedicated lanes and a country where most Americans can walk to transit.

"What's holding transit in the U.S. back is largely it's bad service," she said.

If Kansas City has $8 million to spend on transit, Richardson said, it would be better spent on improving quality. Without better service, free transit would do little to ease car congestion and help the environment, she said.

"We reduce emissions by getting more people to ride transit," said Richardson, who isn't convinced free transit would increase ridership.

Wu said better and free transit is an environmental necessity. When her office surveyed Boston youth about how they'd like to travel in the future, the majority said they wanted to use cars because public transit was expensive and unreliable.

"If we are talking about climate change being a problem we need to fix and we are still not doing everything today to make sure people today — and especially our young people — are enjoying and experiencing transit at the level they deserve, we are in a lot of trouble," she said.

Stances like Wu's and Lucas' are coming at a time when fare costs have been increasingly scrutinized around the world. Mass demonstrations swept Chile last fall after a group of students purposefully evaded fares in protest of a 4 percent fare hike.

In New York City, racial justice advocates have been protesting the addition of 500 police officers to patrol the subway system, supposedly to crack down on fare evasion. The New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority says it will save over $200 million that is lost to evasion in four years but will spend around $249 million to pay the officers enforcing fares over the same period.

Activists say the added officers serve only to further criminalize the city's poor, as well as black and brown people, who are disproportionately targeted in fare evasion arrests and will be affected the most. Decolonize This Place, a group leading major protests against the addition of police officers, calls for free transit in its demands.

But it remains unclear how much of a boon free transit would be to ridership levels. In France, the city of Dunkirk experienced up to an 85 percent increase in ridership on bus routes after eliminating fares in 2018, but Richardson said transit systems in much of Europe are far more robust than in the U.S., making it difficult to compare the two.

Still, she acknowledged, free transit would be massively beneficial to low-income subway riders. But cities should consider alternatives to eliminating fares, Richardson said, suggesting that they decriminalize fare evasion, make sure fare inspectors are unarmed, offer low-income residents fare passes and provide all-door bus boarding to speed service.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news

If Kansas City implemented those changes, it would improve service and guarantee mobility to more people while providing much-needed revenue to the public transit system, she said.

Lucas, the mayor, said he believes zero-fare transit is one of many policies that can address racial inequality in a city still grappling with a legacy of segregation. To this day, a dividing line, Troost Avenue, segregates much of the city's population, with primarily black residents east of Troost and white residents west of it.

The annual average household income one block east of Troost is $20,000 less than it is one block west of the line, said Brent Never, a public affairs professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, adding that in some ZIP codes on the east side, people live 15 years less on average than in areas west of Troost.

But some transit experts are skeptical about how much free buses could collapse decadeslong racial disparities in Kansas City.

Wu of Boston said the zero-fare proposal is gaining steam there even though the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority says it gets one-third of its $2.2 billion annual budget from fares.

"This would be life-changing in terms of the opportunities it would open up, particularly for residents who are faced with the cost of being poor right now," she said.