In December 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice published data that pointed to a troubling development inside the nation's lockups: a rise in the number of inmates who were taking their own lives. Suicide had become the leading cause of death in jails, and hit a 15-year high in federal and state prisons.

This data, which covered the years up to 2014, indicated that America might not be doing enough to prevent suicides behind bars.

But despite warnings from lawyers and researchers of the worrying trend, there have been no updates to those reports, leaving the country stuck, data-wise, more than four years in the past.

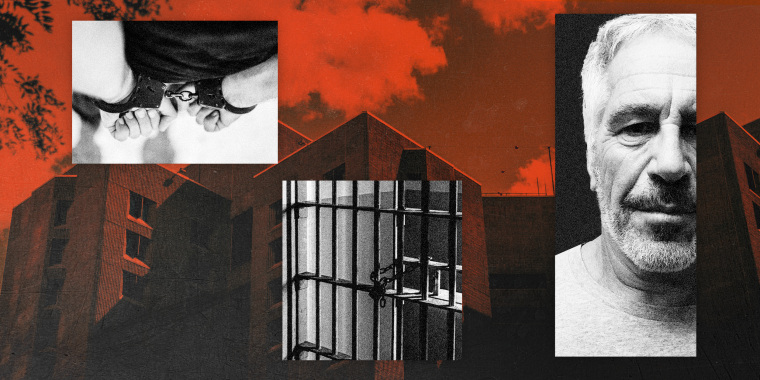

That shortcoming has become more glaring in the days since financier Jeffrey Epstein is believed to have killed himself early Saturday in a federal detention center while awaiting trial on sex trafficking charges. As the Justice Department's inspector general and the FBI begin investigating how Epstein was apparently able to hang himself in the Manhattan facility, the case has brought new attention to the problem of inmate suicide — and the lagging data.

"We as a country should know how many people die in our custody. Period," said Lindsay Hayes, a researcher at the nonprofit National Center on Institutions and Alternatives who helps jails and prisons develop policies to curb suicides. "With our technology, with our industry, with everything we are, for someone to ask about how many people have died in our custody and we do not know, that’s pretty embarrassing for our country."

The Justice Department agency that publishes data about deaths in jails and prisons, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, said Tuesday that staff turnover had delayed the release of more recent results. The federal Bureau of Prisons, which oversees federal lockups, did not respond to a request for more recent data on suicides in its facilities.

The 2016 reports included some unsettling data. In jails, as of 2014, suicides accounted for nearly a third of all deaths, more than any other cause. In state prisons, suicides jumped 30 percent from 2013 to 2014, and represented 7 percent of all deaths in such facilities, the largest proportion since 2001. The 2014 suicide rate in federal prisons was the highest since 2001.

Since then, in the absence of federal data, researchers, lawyers and journalists have found other ways to measure suicides in American jails and prisons, linking the problem to a rise in the number of mentally ill and drug-addicted people behind bars and the continued reliance on solitary confinement.

An investigation by The Associated Press and the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service found hundreds of lawsuits against local jails alleging mistreatment of inmates, many of whom took their own lives while incarcerated. The Marshall Project used public records laws to obtain suicide data from the federal Bureau of Prisons, which showed a rise since 2015 in the total combined number of suicides, suicide attempts and self-inflicted injuries in federal prisons. A rash of suicides in Alabama prisons prompted a judge in May to order the state's Department of Corrections to address "severe and systemic inadequacies" in its mental health programs. The AP found this year that suicides in Texas prisons had tripled in the last decade.

That works gives glimpses of a problem, but not enough to fully understand its scope, David Fathi, director of the National Prison Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, said.

"In most prisons and jails I’ve seen — and there are exceptions — suicide prevention is a joke," Fathi said. "We have seen people able to attempt suicide while supposedly on constant suicide watch. We've seen people taken off suicide watch because staff thought they were OK, and then kill themselves that same day. We’ve seen officers who were supposed to be watching someone on suicide watch actually sleeping.

"A meaningful suicide prevention method is often nonexistent and there's often a real culture of indifference around this, where preventing prisoners from hurting or killing themselves is just not a priority."

To reduce suicides, prisoner advocates and mental health experts say that jails and prisons should invest in mental health resources, offer more drug treatment programs and reduce the use of solitary confinement.

Epstein's death, and its cause, remain under investigation. He was not on suicide watch when he died, and Attorney General William Barr said there were "serious irregularities" at the federal detention center where he was being held. NBC News has reported that corrections officers were supposed to check on inmates in Epstein's unit every half hour, but that hours went by with no checks before he was found dead.

Eric Young, president of the American Federation of Government Employees' Council of Prison Locals, which represents federal prison workers, said he didn't think the number of suicides in federal prisons had increased much in recent years. Epstein's death, he said, has brought an unfair amount of scrutiny to the suicide issue — and prison staff.

He said that not enough attention is being paid to a chronic staffing shortage that has forced corrections officers to work long hours of overtime, making it more difficult to do their jobs properly.

"We don’t believe it’s a significant trend," Young said of suicides in federal prisons. "It's on par for where we usually are at this point in the year."

Asked for data showing that, he deferred to the Bureau of Prisons.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.