Thousands of people have said no to Erica Elson.

For four years, the Hollywood TV writer worked as a telemarketer peddling subscriptions for the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Los Angeles Opera.

“I needed a part-time job to have some regular income,” she said. “I played piano as a kid, so I was really into music and it was down the street from where I was living.”

Elson figures she was turned down 96 percent of the time, often rudely. But it was that 4 percent when she made a sale that made up for all that rejection.

“I was making more money than I would if I was working at a coffee shop,” she said.

And Elson appears to have had a typical batting average in an industry where about 93 percent of telemarketing calls end in failure, according to the most recent numbers from the now-defunct Direct Marketing Association, which is now part of the Association of National Advertisers. NBC News reached out to the ANA for an update on the state of the telemarketing industry but received no response.

"Their success rate is not very high, but all they have to do is crank up the dial and call more numbers," said consumer advocate Roger Anderson who runs the Jolly Roger Telephone Company and who dreams up new technologies designed to drive telemarketers nuts, if not out of business. "Someone will buy."

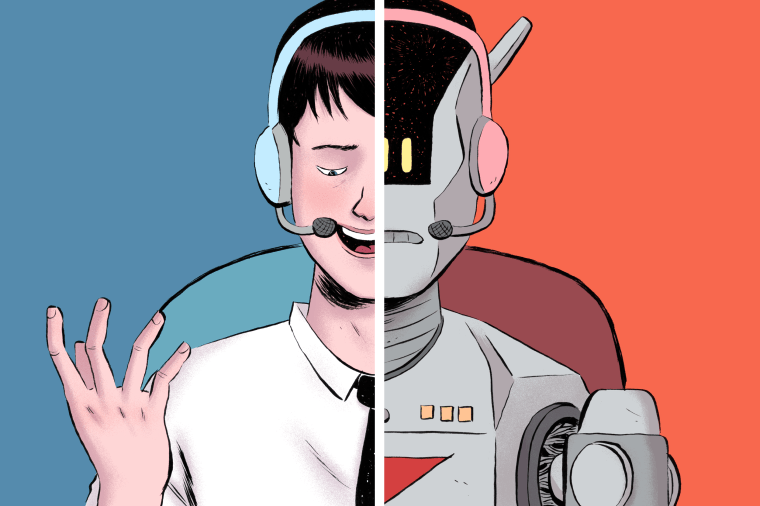

But more and more, in the era of seemingly endless robocalls, telemarketers are facing existential threats that experts say could make this much-derided profession a thing of the past.

“The initial ‘dialing’ is almost always automated nowadays, and then the human telemarketer takes over once a live prospect is engaged,” said Charles D. Morgan, CEO of First Orion, an Arkansas-based telecommunications company. “As artificial intelligence advances and we struggle to differentiate between robots and humans, then human telemarketers should sharpen up their resumes.”

At a time when just about anybody with a phone has had to contend with complete strangers peddling vacation packages or insulated windows, or pulling heart strings on behalf of police groups or cancer victims, consumer advocates say it’s not a moment too soon to do something.

“In general, unwanted calls — including telemarketing, robocalls, spoofing and combinations of these — are consistently the top consumer complaint category received by the commission and our top consumer protection priority under Chairman [Ajit] Pai,” said Will Wiquist, a spokesman for the Federal Communications Commission.

To make matters even more difficult for telemarketers, who like Elson might rely on the job for income, local governments are no longer waiting for Washington to turn the screws tighter on the industry to protect consumers.

In business-friendly Indiana, for instance, where some 2.1 million people are already on the state’s “Do Not Call” list, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are talking about tearing up the existing protections and imposing even stricter rules to rein telemarketers in.

“I favor a complete overhaul of the system,” state Rep. Ryan Hatfield, a Democrat from Evansville, said. “The federal rules are not keeping up with the current technology. I think both Democrats and Republicans recognize that.”

Why, in the face of such public opposition and scorn, do telemarketers persist? Because they are part of an industry that is still making money.

That's especially true when it comes the scammers — who increasingly employ machines, not people, to achieve their shady goals.

Mobile scam calls have increased from 3.7 percent of total calls in 2017 to 29.2 percent this year, Morgan said in an email to NBC News. And his company projects the figure to reach 44.6 percent next year.

“It is easier than ever for scammers to make billions of automated calls for dirt-cheap — and their tactics works,” Morgan said. “Last year, scammers raked in close to $10 billion, so they are inclined to keep dialing. Scammers will frequently illegally ‘spoof’ caller ID information for a trusted party like your bank or a number with the same area code to convince you to pick up the phone which gives them the opportunity to work their magic.”

When it comes to solicitations for institutions or charitable causes, however, it's still more likely than not to be a human on the other end of the line.

“For now, human telemarketers are not in any immediate danger because engaging a prospect is far too nuanced for a robot and consumers are much more comfortable talking with a human that a robot,” said Morgan.

The obituary for the telemarketing industry has been written before.

In 2007, Entrepreneur magazine said the industry would be close to extinction in a decade. “The good news for people who hate telemarketing calls is that the industry may finally be dying; the bad news is that it may take a while,” the magazine wrote.

Five years after the national Do-Not-Call list was established, enabling consumers to block some telemarketers, the industry still managed to bring in $393 billion in revenue in 2006, the magazine reported.

“They’ll be here,” according to the magazine. “Humbled, more impotent, but probably still here.”

Elson, who worked as a telemarketer from February 2012 through April 2014 to make ends meet while she was launching her writing career, said she doubts robots will completely replace real people.

“The more you sound like a real person who is excited about something the more likely you make a sale.”

Elson, who has written about her experiences, said most of the people they were tapping were either past subscribers or fit a demographic of people likely to subscribe, adding that they would have been put off by robocallers from the outset.

“I don’t think people, especially older people who don’t use the latest apps/websites to buy tickets, would be interested in buying such expensive tickets if they were asked/reminded to do so by a robot,” Elson wrote in an email. “It’s also much easier to hang up on a robot.”

Elson said she worked four-hour shifts, six days a week. “You could do a double, but I would normally keep it to four hours because it was exhausting,” she said.

“You walk in, stick all your personal effects in a cubby, put on the headset, log in, hit a button and autodial,” she said. “They set you up with hundreds and hundreds of leads.”

Each would display what was known of a potential customer’s past history of subscriptions or donations, things like best time to call, any past problems or complaints, even the names of friends who have subscriptions.

Elson said they underwent training and were given a script that she quickly ditched.

“What I found worked was the personalized approach,” she said. “I think my niche, when I was calling older people about opera, I knew about opera and they found it endearing.”

Working for the philharmonic was far more stressful, she added.

“My boss would walk by and say: 'Are you selling? Are you selling?'" she said.

And the people who worked at the call centers were people like her, Elson said.

“In L.A., there are so many people who come out here for film,” she said. “A lot of people who worked there needed the flexibility to go to auditions. So there were lots of creative people, actors, musicians, writers.”

There were also quite a few elderly people padding their retirements.

“A lot of them were passionate about music,” Elson said. “They were into it, so they were very successful.”

Elson said she was lucky to have worked for an operation that paid a guaranteed minimum wage plus commission. There are dozens of examples of telemarketing companies that don't and take advantage of telemarketers.

One led the U.S. Department of Labor to sue an outfit called Wellfleet Communications two years ago over allegations that the Las Vegas-based telemarketing firm stiffed workers on overtime pay and did not even pay minimum wage. Wellfleet filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit and the case remains unresolved.

Then there was the Philadelphia-area telemarketing firm that actually docked the pay of workers when they left their stations to use the bathroom or eat lunch.

A federal judge in 2016 found American Future Systems, aka Progressive Business Publications, and company owner Edward Satell liable for $1.75 million in back wages and damages to more than 6,000 workers who worked in 14 call centers in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Ohio.

Sateli appealed but the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the government in January.

Meanwhile, Anderson of the Jolly Roger Telephone Company is fighting telemarketers and robocallers with robots of his own that waste their time by engaging them in meaningless conversation — and never agree to buy a thing.

But Anderson is under no illusion that his robots are going to drive human telemarketers completely out of business.

“The human telemarketer is going to have to get more specialized,” he said. “No matter how sophisticated robots get, right now you still need a human to close the deal.”

Priya Raghubir, a marketing professor at New York University, agreed.

“I think there will always be a place for an annoying human being to call you,” she said. “When you have a human being on the line, you do have a much greater opportunity of making a sale. And the telemarketing industry knows that.”