The adult children of Heriberto Carrillo anxiously waited by their phones after news broke last month that a U.S. Forest Service firefighter had died battling a Southern California blaze ignited by a gender reveal stunt gone terribly wrong.

Heriberto Carrillo Jr. kept looking at his phone, hoping that his mother wouldn't call to say that his father had been identified as the fallen firefighter.

He went through a mixture of emotions — sadness that someone had died, worry that his father had been injured and anxiety over not knowing if he was still alive.

"It's so stressful," Carrillo Jr. said. "You’re waiting for that phone call, but you're not wanting that phone call."

When he finally spoke with his mother, she had good news — his dad had been fighting a different fire, the Bobcat Fire in the Angeles National Forest, and was safe. The fatality occurred east of Los Angeles in the San Bernardino National Forest during the El Dorado Fire.

"We try to go about our lives, but it's always in the back of our minds that something could happen," Carrillo Jr. said.

Heriberto Carrillo Sr. is one of the thousands of U.S. Forest Service firefighters who have fanned out across the West Coast to fight blazes in California, Oregon and Washington during yet another record-setting fire season.

In California, more than 3.7 million acres of wilderness have been destroyed and nearly 30 lives lost this year alone, according to Cal Fire data. As of Thursday, firefighters were struggling to combat more than 8,100 fires across the state.

Fire season is not new to the American West but the length and ferocity of the season worsens every year. Cal Fire estimates that fire season has increased by 75 days across the Sierras and corresponds to an increase in intensity of forest fires in California.

Federal wildland crews are sometimes the last line of defense and are often called in after local resources are depleted. They crisscross states throughout the fire season and are typically considered seasonal employees who are paid to work from May through October.

Whenever a firefighter dies, even if it's in another state, Carrillo and his crew observe a moment of silence.

"When we’re all together, it’s like we’re family," Carrillo said.

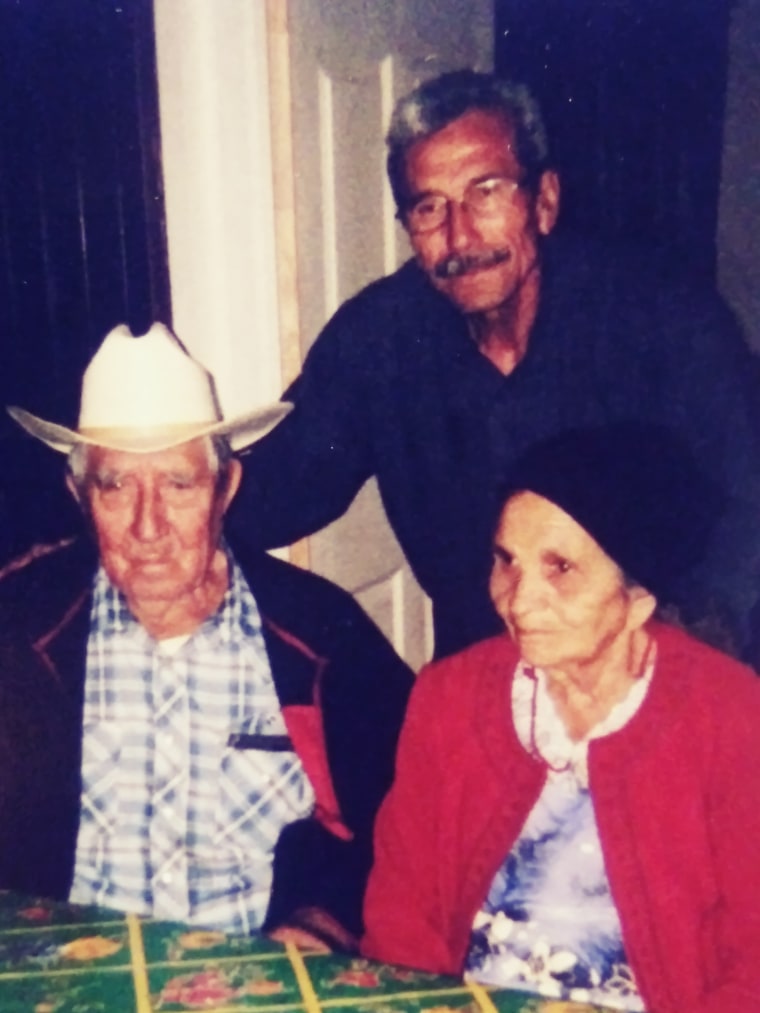

At 68, Carrillo stands apart from many of his colleagues. He has more than 40 years experience and has no intention of retiring any time soon. He is 10 years older than the next senior crew member, Carrillo said.

"I thank God I still have the energy," he added. "I like working outside in the mountains and using a chainsaw."

Carrillo became a wildland firefighter in 1976, just two years after immigrating to the United States from his native Mexico. He was in his early 20s at the time and a friend encouraged him to apply for a job as a firefighter.

Carrillo immediately liked the work but was forced to find another job because of the seasonal nature of the industry. He became a fieldworker, picking fruit in the farms of Central California that feed much of the nation. When he isn't fighting fires, Carrillo is tending to orange, apple, cherry and olive trees.

"That’s what most Mexican men do," Carrillo Jr. said of his father. "They're going to work until the day they die."

Despite his usual calm under pressure, Carrillo recently found himself in the middle of the worst fire fight he has faced in 43 years on the job.

It was one day before he was scheduled to return home to Central California. He had already spent 13 days in the Angeles National Forest above Los Angeles fighting a stubborn wildfire that threatened to consume the historical Mount Wilson Observatory and its priceless telescopes.

Earlier in the day, Carrillo had carried three fire hoses to a controlled burn near the observatory in an effort to prevent the larger Bobcat Fire from destroying the famed campus. Suddenly the wind changed direction and Carrillo and nearly 20 other firefighters were encircled by flames.

"He said it was the toughest fight of his life," Carrillo Jr. said. "He never had to work so hard to survive."

When asked about the incident, Carrillo was unfazed.

"It's like anything else," he said. "I just thank God nothing worse has happened."

Even at his age, Carrillo shrugs off the danger and physical strain of being a federal firefighter. He said that he's "used to it" now and uses his own endurance to test and inspire some of the younger men and women who serve alongside him.

He stays in shape during the off season by climbing up and down 60-foot ladders in the fruit fields. When he's picking oranges, he carries 80 pounds of them at a time, he said.

"He likes to tell his guys that some of them weren't even born yet when he first started," Carrillo's daughter, Lillian Alonso, said. "Whenever he sees someone not doing their job well, he will go out and show him."