Mike Tyran, a nurse living near Corpus Christi, Texas, bought a used Apple iPod in 2010 and tried to repair it after the battery wouldn't charge.

But when the inveterate "fixer" attempted to open the white-and-chrome rectangle, he was stumped.

First of three parts

"I had worked on old tube radios ... (which) had diagrams (and) ... schematics. I know where the wiring goes and I know how to open it," said Tyran, 56, a former heavy diesel mechanic. "I looked at an iPod and I had no idea how to open it … because there were no screws."

Tyran's realization that the sleek but defective digital music player was nearly impenetrable opened his eyes to a broader truth: He and his fellow tinkerers are living in a New Age of Obsolescence — a time where repair is, by design, often not an option.

There are many reasons that consumer products are increasingly manufactured in ways that make it nearly impossible to fix them.

Among them: Ever-tighter design requirements, manufacturers' fears of intellectual property theft or liability if a repair goes wrong, and the growing number of products that contain proprietary software — a class that will explode in the era of the Internet of Things.

But critics say profit generated by repeat product sales is the biggest driver behind disposable consumer products.

"These companies are prioritizing their bottom line at the expense of the rest of us," said Kyle Wiens, CEO and co-founder of iFixit, a wiki-based repair website. "It's possible to make repairable, long-lasting electronics, but if they did that it could hurt their future sales. They're putting us on a treadmill where we're forced to buy new gizmos every couple years, whether we want to or not."

The practice has stark implications not just for consumers and a dwindling number of independent repair technicians but for the environment, as even electronics recyclers are increasingly unable to physically separate product parts to be used again.

A study conducted by the United Nations University, a global think tank, found that consumers around the world trashed 92 billion pounds of electronic waste in 2014, everything from lamps to laptops. That number is forecast to increase to 110 billion pounds by 2017 — a jump of nearly 20 percent.

So far, only about one-sixth of electronic waste is being recycled, it said.

That problem is compounded by the fact that many electronics products contain toxic elements like lead, mercury, beryllium and cadmium, making recycling more difficult and expensive.

A big contributor to the disposability problem is the move by electronics and personal computer manufacturers to turn previously replaceable parts like batteries into fixtures that essentially determine the life cycle of a product, a practice that Wiens traces to Apple.

Related: Old TVs Create Toxic Problem for Recycling Programs Across America

"The iPod was the first mainstream device ... that had a battery that couldn't be swapped out," he said of the change in 2001. "Now we're seeing it integrated into more and more things: the USB headphones ... (and) Bluetooth headsets that you buy."

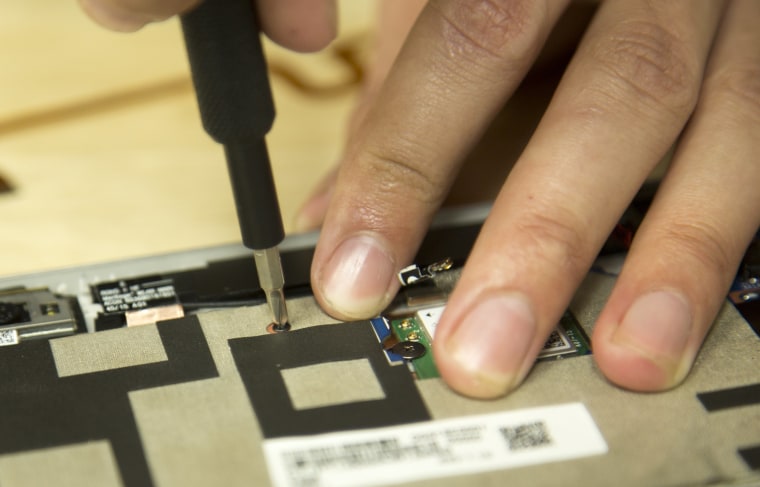

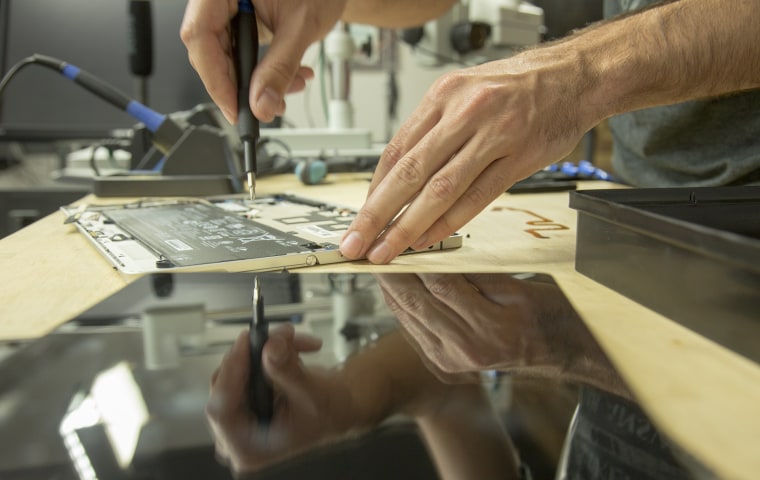

Technically, the batteries in iPods and other similarly barricaded products are replaceable, though doing so means removing interlocking parts, a procedure that often requires proprietary or specialized tools, then extricating them from glue used instead of screws to hold them in place.

Some products, such as the Microsoft Surface tablet, are so fortified that even experts can pretty much count on destroying the first one that they work on, according to Wiens.

In a statement to NBC News, Microsoft said, "As is the case with many products, Surface is built by professionals and is intended to be serviced by professionals. Surface is comprised of high-quality components, and we stand behind our warranty and the cutting-edge materials used to create these unique and powerful devices."

Professional repairers -- particularly independents -- also are often stymied by restrictive manufacturer agreements that limit access to replacement parts to "authorized" technicians and an explosion of product models that makes recycling used parts into existing devices difficult.

Such challenges largely explain why the U.S. electronics and computer repair industry contracted by 1.2 percent per year between 2010 and 2015, according to IBISWorld, a market research firm. It projects further declines at least until 2020, stating that the "industry is in the decline stage of its life cycle."

That also may be true for consumer products in general, as disposability practices pioneered by electronics manufacturers spread to other industries.

"Manufacturers, in order to compete in the market, are continuously reducing the production costs and with it, the planned lifespans."

A study this year by the Oeko-Institut, a German sustainability research group, found that the percentage of home appliances replaced by their owners within five years for defects more than doubled in eight years, from 3.5 percent in 2004 to 8.3 percent in 2012.

Siddarth Parkash, one of the study's co-authors, says the problem likely will worsen.

"I fear that this downward trend might continue because manufacturers, in order to compete in the market, are continuously reducing the production costs and with it, the planned lifespans," he said by email.

{

"ecommerceEnabled": false

}"Reducing costs means compromising on the quality control of the materials, components and supply chain as well as avoiding comprehensive lifetime and durability tests for the products. To make things even worse, consumers are becoming accustomed to shorter lifespans."

Product obsolescence and a proclivity for trashing over repairing is, of course, nothing new.

"In America, we invented disposability," said Giles Slade, the author of "Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America."

The 19th Century is often wistfully remembered as the age of durability, when products were made to last and passed down as heirlooms. But Slade said that began to change in 1890, when a watchmaker named Robert Ingersoll priced his watches at $1, meaning that when one broke it was easier — and often cheaper — to simply throw it away and buy a new one.

The concept of planned obsolescence picked up steam in the 1920s in the auto industry. Henry Ford believed that a durable, long-lasting product would win loyalty from owners and eventually generate repeat sales. But General Motors' Alfred Sloan pioneered the yearly model upgrade that encouraged consumers to purchase a new car long before their current ride was worn out. Eventually, Ford was forced to follow suit after GM's approach proved a dramatic winner in the marketplace.

What's changed in the past 10 years is that the instead of dissuading consumers from repairing products, manufacturers are now making it near impossible to do so, said Slade.

Consumers bear some responsibility for that shift, said Wiens, even though manufacturers have been far from transparent about the choices they are offering them.

He pointed to a market test that Apple did in 2012: It offered both the traditional Macbook Pro with an easily unscrewable base, removable RAM and drives, and a screen that separated from the display, allowing for easier and cheaper repair. The other option was the Retina version: slimmer, sleeker and at the time one of the least-repairable computers on the market, according to Wiens.

Consumers chose the Retina in droves.

"The Retina Macbook Pro on the laptop side of things was, for me, a red line that Apple crossed" on a road to "design anorexia," said Wiens, referring to the ongoing trend of designing computers for thinness at the expense of repairability. (Apple declined to comment in response to a request from NBC News about its manufacturing practices.)

"The capability to repair is (only) possible if you have the part."

Design constraints are just one impediment facing determined product owners and professional repairers.

"The capability to repair is (only) possible if you have the part," said Willie Cade, the CEO of PC Rebuilders & Recyclers in Chicago.

But an explosion of product models has made finding the right part increasingly difficult for repairers like Cade. Today, for instance, Windows is installed on 90,000 device models, many of which require different parts even across a single brand, he said.

Some manufacturers are also revoking repairers' ability to get parts at all.

The last generation of Amazon's Kindle, for example, could be opened and fixed if the battery failed or the screen cracked. The problem is that Amazon refuses to sell spare parts for the Kindle to non-authorized repairers. (IFixit acquires its spare Kindle parts from an electronics recycler.)

Amazon did not respond to a request for comment from NBC News.

Moves like that have taken a toll on the repair workforce, particularly independents.

In 2012, for example, Nikon announced it would no longer make repair parts available to repairers outside of its small authorized network, sinking the number of professional Nikon repairers around the country from 3,000 to 13, according to Wiens.

Nikon did not confirm those figures but said in a statement to NBC News that "Modern digital cameras are extremely advanced and require skilled technicians and specialized tools to properly assure adherence to manufacturer specifications."

The steady erosion of professional repairers in recent years often leaves consumers with little recourse but to participate in the throwaway culture.

Mike Tyran, however, persisted and was eventually able to get his iPod working,with help from iFixit, not Apple. When he called the company, he was told that Apple no longer supported repairs on the device and doesn't make repair schematics available. The best it could offer him was a $50 credit toward an upgrade.

"What it has shown me is the fact that just because we buy a device like an iPod, we do not own it," said Tyran. "This has got to stop. I buy it, I own it. If I want to break it, let me break it. If I want to fix it, let me fix it."

Part 2: How digital copyright law is being used to run roughshod over repairers.