Editor's note: This story is one in a series on a crisis in America's Breadbasket—the depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer and its effects on a region that helps feed the world. Read the previous installment here.

MANHATTAN, Kansas—In America’s Breadbasket, a battle of ideas is underway on the most fundamental topics of all: food, water, and the future of the planet.

Last August, in a still-echoing blockbuster study, Dave Steward, Ph.D., and his colleagues at Kansas State University, informed the $15 billion Kansas agricultural economy that it was on a fast track to oblivion. The reason: The precipitous, calamitous withdrawal rates of the Ogallala Aquifer.

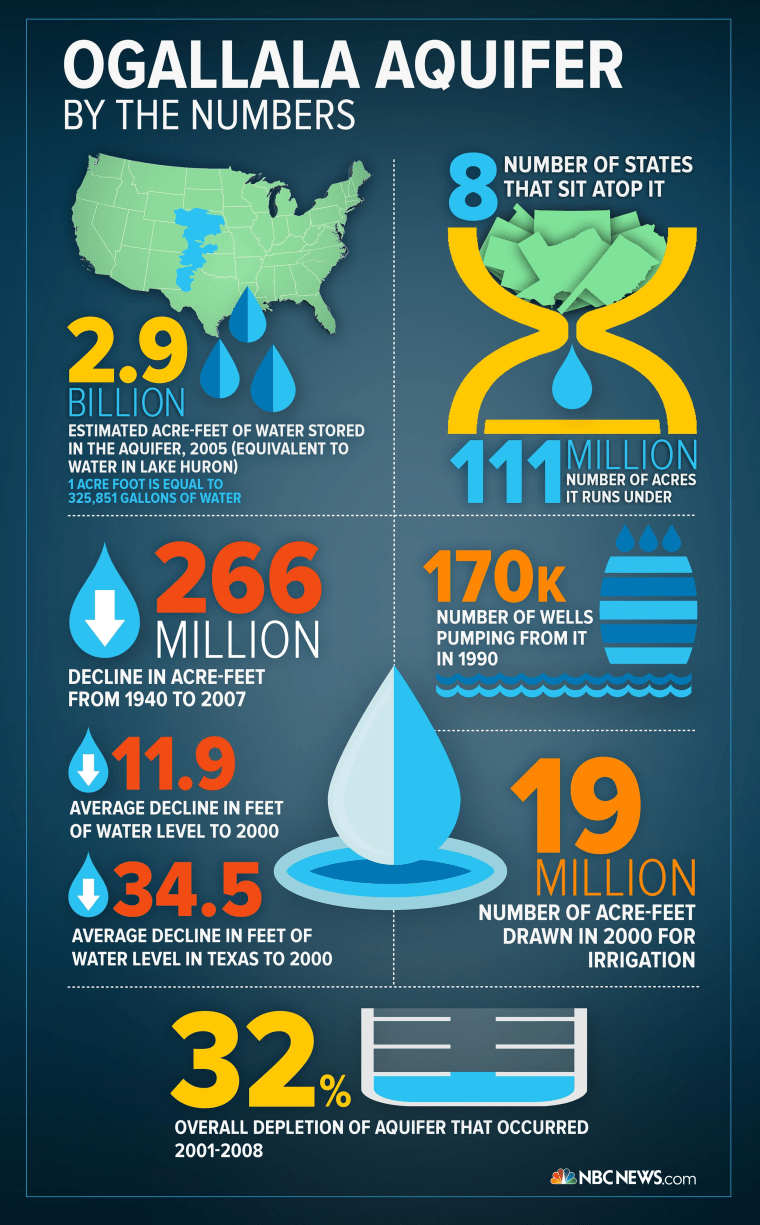

The Ogallala is little known outside this part of the world, but it’s the primary source of irrigation not just for all of western Kansas, but the entire Great Plains. This gigantic, soaked subterranean sponge – fossil water created 10 million years ago – touches eight states, stretching from Texas all the way up to South Dakota, across 111.8 million acres and 175,000 square miles.

The Ogallala supports a highly-sophisticated and amazingly-productive agricultural region critical to the world’s food supply. With the global population increasing, and as other vital aquifers suffer equally dramatic declines, scientists acknowledge that if the farmers here cannot meet ever-growing food demands, billions could starve.

Steward’s study predicted that nearly 70 percent of the portion of the Ogallala beneath western Kansas will be gone in 50 years. He’s not the kind of person to shout these results; he speaks slowly and carefully. Yet, he has the evident intensity of one who’s serving a greater purpose. “We need to make sure our grandkids and our great grandkids have the capacity to feed themselves,” he says.

Now the chief executive of the state, himself from a farming family, is using Steward’s report as a call to action.

“One of the things we [have] to get over … is this tragedy of the commons problem with the Ogallala,” says Governor Sam Brownback, a Republican who at age 29 was the youngest agriculture secretary in state history. “It’s a big common body of water. It’s why the oceans get overfished … You have a common good and then nobody is responsible for it.”

“That’s one of the key policy issues that you have to get around,” Brownback says in his roomy, towering office at the capitol in Topeka. “Everyone has to take care of this water.”

In that spirit, a tiny legion of farmers and landowners in the northwest corner of Kansas, where the Rockies begin their rise, have just begun year two of what could be one of the most influential social experiments of this century.

The group is only 125 in number but controls 63,000 acres of prime farmland in Sheridan County. Collectively, voluntarily, they have enacted a new, stringent five-year water conservation target, backed by the force of law and significant punishments.

The Local Enhanced Management Act, or LEMA, is the first measure of its kind in the United States. Specifically, the farmers are limiting themselves to a total of 55 inches of irrigated water over five years – an average of 11 inches per year.

“My Dad and my uncles gave us this life,” says Mitch Baalman, a farmer, father of four, and one of the vocal proponents of the water restrictions. “And I want to do that for my boys.”

“We had two big John Deere dealerships,” he says. “But one dealership is going away because they weren’t meeting sales. We’re losing that. We have a hospital that employs eighty-something people. We have a 60,000-head-of-cattle feed yard that employs 45 people. If we kept pumping the way were pumping the water out of the Ogallala, the writing was on the wall. We were going to run out.”

Brownback, a practicing Catholic, connects his faith to conservation, and the urgency to protect the Ogallala.

“I think God gave us this beautiful place,” he says. “He gave us a fabulous aquifer, and we need to be responsible with that and see that future generations can use that, as well. There’s also that interesting sidebar: the idea of forming communities, the way Francis of Assisi and many others would look at community … which is: ‘You don’t do this on your own. You don’t do anything on your own. You got a body of people here with you.’ And that’s a central idea around the LEMA. The community helps each other.”

Watch NBC Learn and the National Science Foundation's video on the future of the Ogallala Aquifer.

As the Ogallala is being drained, attention in the High Plains is turning to corn, the crop that’s highest in demand, fetches the highest price and is increasingly controversial.

Corn is a thirsty crop, and some question the inherent morality of using so much land and water to raise it, especially because so little of the corn grown in the U.S. is served as food. It’s either fed to cattle, or made into ethanol. Since 1980, it is estimated the U.S. government has spent $45 billion to subsidize ethanol production.

For farmers like Mitch Baalman, corn presents an immediate math problem. On average, a corn crop needs 24 inches of water during its growing season. But, under the rules of the new LEMA, that total would represent nearly half of his five-year allotment.

“We’re going to have to change the mindset,” Baalman says. “Pull the throttles back. Plant more alternative crops. We’re just not going to be corn, corn, corn—even though that’s what the insurance is telling us and that’s what the government is subsidizing. I would love to raise corn, too. But we can’t.”

Baalman is admittedly more of a CEO than a hands-on farmer. He’d be lost without his virtuoso head mechanic, Marvin Kaus, and his computer guru, Trent Lambert. Baalman’s investment in tractors, sprayers, and combines –as big as a house, as complex as a commercial jet—is $4 million alone.

“If you think New York City is fast,” he says, “it’s just as fast out here.”

When Baalman considers who might follow him among his four kids, he tells you it’s eight-year-old Tucker, the son who has an “awesome story.”

Tucker was born paralyzed below the waist due to spina bifida – a birth defect in which the spine doesn’t close all the way.

“His back looked a zipper that malfunctioned,” Baalman says.

But Tucker already has a quality essential for life on a 21st Century farm, in which the tools of a dizzying digital age must maximize the capricious elements of sky, soil … and water. “He has,” says Dad, “the patience.”

In a state where the governor, the academic community, and its farmers are united by forward-thinking solutions to the critical issues of land and water, it’s also logical that Kansas is the home of a progressive, influential agricultural think tank, with a resident sage preaching the gospel of a New Agrarianism.

Wes Jackson started the Land Institute out of a converted schoolhouse at the edge of Salina, Kansas. A plant geneticist, Jackson’s big idea is creating new perennial, hybrid versions of corn and other grains used to supply our essential carbohydrates, such as wheat and rice.

A perennial – unlike an annual – doesn’t die after it flowers, but instead becomes dormant until the next growing season. And it uses far less water.

Josh Svaty, vice-president at The Land Institute, and the state’s second-youngest secretary of agriculture after Brownback, highlights how perennials make sense for a region facing a dire water crisis—and an earth that scientists predict will be increasingly drier and hotter from the effects of climate change.

“If you have a perennial cover,” he says, “that plant can take the moisture, store it, use it more wisely than an annual system. And though some annual plants, like corn, grow a big root system, that’s only at the end of their life cycle … whereas a perennial plant has 10-feet of root system in the soil, year after year. It can really take advantage of the exchange of nutrients and the exchange of moisture.”

Perennials would also, in theory, disrupt and reboot the entire agriculture industry. To plant annuals, farmers typically pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for seed every year – which doesn’t include the added necessary inputs of fertilizer and pesticides. But those costs would diminish if the world ever turned fully to perennials, since they flower for multiple seasons. By extension, the massive $50-billion seed business – with major global players such as Monsanto, Du Pont Pioneer and Syngenta – would be dramatically affected.

“When I first published in 1977, I said it’s going to take 50 to 100 years to develop perennials,” Jackson says. “Well, we’re on schedule, but it’s going to take more time. We need more people doing it. In fact, we need to institutionalize this idea. And we’re taking steps to do that now in a coalition involving Kansas State. We’re finally getting traction, partly because of our success, but also because the anxiety is going up, up, up.”

Jackson, 78, sees the human race on a swiftly suicidal course unless we muster nothing short of an ecological and moral revolution.

“The Declaration of Independence said that we’re all created equal,” he says. “But the Constitution allowed for slavery. So we had the land of the free and the land of the slave. We had the high moral and we had the legal. Six-hundred and fifty-thousand deaths later in the Civil War, we got that reconciled.

“So now we have the high morality of the need to protect the ecosphere. But it’s legal to rip the tops off mountains. It’s legal to drill in the Arctic. It’s legal to drill in the Gulf. It’s legal to build pipelines. It’s legal to send carbon into the dumping ground called an atmosphere. So we’ve not yet reconciled the high moral with the legal.”

“That’s why,” he asserts, “my grandchildren could be the most important generation since the walk out of Africa.”

With additional reporting by Gil Aegerter.