In a recent TikTok video, 98-year-old Lily Ebert told her 1.9 million followers about the Auschwitz number tattooed on her forearm: A-10572.

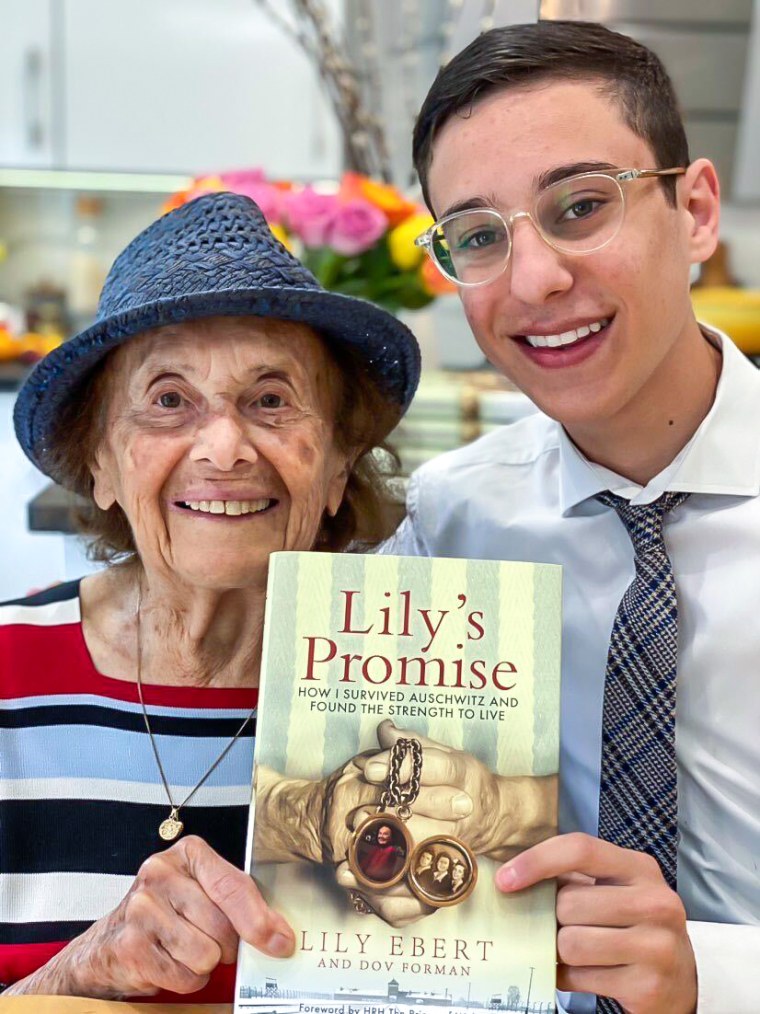

Like many Holocaust survivors, Ebert didn’t talk about the experience for decades. But then her great-grandson Dov Forman started recording her stories and posting them on TikTok, including the 24-second video about her tattoo that has drawn more than 22 million views.

“We were a number and we were treated only like numbers,” Ebert said in the video.

Ebert, who was on one of the last trains carrying Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz in 1944, and Forman are among a growing group of influencers and regular people using social media to educate their followers about the Holocaust, in which 6 millions Jews were exterminated by the Nazis during World War II.

The accounts are becoming popular at a time when the number of living survivors is dwindling and Holocaust educators are trying to figure out how to preserve firsthand testimonies in a way that is accessible to a new generation.

Creators say the work has become increasingly important as celebrities with large followings, such as Ye, the rapper formerly known as Kanye West, and the NBA's Kyrie Irving, have made antisemitic comments recently. West has 31.8 million followers on Twitter. The Jewish population worldwide is 15.3 million, according to The Jewish Agency for Israel.

People who use their accounts to educate followers say it’s difficult to understand the severity and scope of the Holocaust through textbooks and history lessons alone. TikTok allows survivors to speak to a generation that may know little about the genocide in Europe.

Forman started his great-grandmother’s TikTok during the pandemic when he was 16 years old: “I said to her, ‘I want to start uploading videos of your story on Tiktok.’ And at first, she laughed and she said, ‘I’m not dancing.’”

Less than two years later, the account has 32.2 million likes, over 500 videos, and the two have published a best-selling memoir, “Lily’s Promise.”

“I could never have dreamt that we could reach as many people as we do on social media,” Ebert said in an email to NBC News. “My generation is the last one to have witnessed the Holocaust. What will happen when the last of us are gone?”

That’s a question TikTok influencer Montana Tucker, 29, is trying to answer. The social media sensation known for her lighthearted dance videos has 8.7 million followers on TikTok and 2.8 million on Instagram.

Those followers are learning through her new TikTok documentary series “How to: Never Forget” that she is also the granddaughter of two Holocaust survivors.

She traveled to Poland recently to retrace her grandparents’ experience during the Holocaust with Zak Jeffay, a Holocaust education guide with JRoots, an organization that takes young people to historical Jewish sites around the world.

In 10 two-to-three-minute episodes, Montana takes her millions of followers with her to Poland, where an estimated 2.9 to 3 million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust. The series leads up to visiting Auschwitz, the largest and deadliest concentration camp run by the Nazis.

In June 1944, Tucker’s grandmother Lilly Schmidmayer was taken to Auschwitz by train with her mother and her mother's sister. When they arrived, Schmidmayer was separated from her mother, who was killed in a gas chamber.

A total of 1.3 million people were forcibly transported to Auschwitz by train, and 1.1 million of them died, including over 900,000 Jews.

“This is now my responsibility to get out there because who’s going to speak for them in a few years when there are no more Holocaust survivors left?” Tucker said. “I have this platform now, I can reach millions of people. I have a big Gen Z, younger following.”

The producing team of Israel Schachter and Rachel Kastner, with SoulShop Studios, shot over 100 hours of footage in June for “How To: Never Forget” and have spent the last few months editing the material.

“We went there for a week,” Kastner said. “It was really intense, really emotional.”

The granddaughter of three Holocaust survivors, Kastner made a full-length feature documentary “The Barn,” released in 2019, about her grandfather Karl Shapiro's reunion with Paulina Plostkaj, the woman who saved his life by helping his family find a place to hide.

While documentaries are a powerful way to share and preserve survivors’ stories, Kastner said, she believes Holocaust education must meet Gen Z where they are, which is on social media.

“If we’re not innovating the way that we’re telling our stories, we’re going to find out that nobody’s listening,” Kastner said.

In a 2020 nationwide survey of millennials and Gen Zers, generally those born in the late 1990s to early 2010s, 63% of those surveyed did not know that 6 million Jews had been killed in the Holocaust.

Holocaust denial and distortion are prevalent all over social media, according to data from the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) published this year, which said 16.4% of content related to the Holocaust denied or distorted the genocide. On Telegram, it was 49%, on Twitter 19% and on TikTok 17%.

The Center for Countering Digital Hate, a nonprofit that fights online hate and disinformation, found in 2021 that 84% of antisemitic content reported to social media companies is not removed.

In January, TikTok joined with UNESCO and the World Jewish Congress, an international organization that represents Jewish communities, to combat Holocaust denial and distortion by redirecting users who searched for terms relating to the Holocaust to verified information.

Melissa Mott, director of antisemitism, Holocaust and genocide education at the Anti-Defamation League, said Holocaust denial is an indisputable element of antisemitism, which is on the rise. Last year, the ADL found 2,717 antisemitic incidents across the U.S., representing a 34% increase from 2020.

Mott said that “inventive storytelling methods,” like showcasing survivors and their descendants on social media, is “a really important and nuanced way to tell that story.”

Gidon Lev, 87, who arrived at the Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic when he was 6 years old, shares stories from his life and survival testimony to his 407,000 followers on TikTok with the help of his partner, Julie Gray.

For survivors like Lev, sharing their testimonies is difficult because it forces them to relive the trauma. Many of the creators behind accounts that feature survivors, like Gray, are usually younger and not survivors themselves.

“It’s a big responsibility, and I ask myself every day, ‘Is this good for Gidon?’” Gray said. “I don’t want to harm him. Is it too much? Is it emotionally stressful?”

Lev said that, through TikTok, he has been able to have some influence on young people’s understanding of the Holocaust, and he thinks the current situation will improve if people listen and pay attention to stories like his.

“Let the people who know the truth speak out and speak up,” he said.