When nationwide protests against police brutality and racism reached Lansing, Michigan, last spring, John Edmond heard calls to slash the local police budget and found it a little extreme.

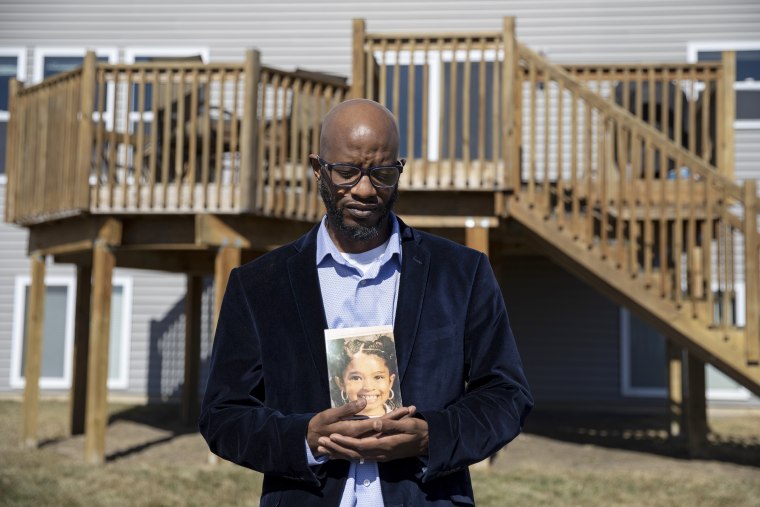

Edmond, 43, a Black man who said he’d been profiled by police when he was younger, understood the anger that fueled the marchers. But he also saw the demands through the eyes of someone who’d lost a child to gunfire.

“If you take away resources from the police, that takes away an opportunity for us to get justice,” he said.

His 7-year-old daughter was killed in a 2010 shooting that helped spur the creation of a special police unit targeting violent crime. In the protests’ aftermath, police officials warned that the unit — and the jobs of many officers — might not survive if their budget was cut.

That argument gained power as a surge in gun violence drove homicides to a 30-year high in Lansing, the capital of Michigan. In the fall, the City Council rejected a proposal to cut the $46.5 million police budget in half over five years and instead endorsed hiring more social workers.

After the death of George Floyd spawned a movement to curb police power in America, a rise in violent crime in many cities has served as a counterweight, making radical changes harder for some of the public — and some elected officials — to accept.

In Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed by police, the City Council proposed eliminating the police department in June. While the council forced some cuts, by February, following a dramatic rise in violent crime, it agreed to hire more officers. In January, Salt Lake City’s council lifted a police hiring freeze imposed during the Floyd protests as violence spiked. Atlanta, where homicides hit a 20-year high, increased its police budget last summer. A survey of mayors released in January showed that a vast majority thought their police budgets shouldn’t significantly shrink.

In Lansing, a city of 118,000, Mayor Andy Schor has backed changes to police operations but opposes cuts to the police budget. Police Chief Daryl Green said that he has fought off the City Council’s attempts to reduce funding to his department by highlighting the rise in violence.

“I start talking about the crime rates,” Green, who is Black, said in an interview. “Aggravated assaults are up, domestic violence, even simple assaults are up. All violent crimes for the most part are up. I start sharing those statistics and our ability to focus on keeping citizens safe. I argue that we are underfunded by 50 or 60 officers. I think that’s been effective enough.”

That has frustrated activists who say it isn’t police cutbacks that drive up crime, but neglect of social services and programs that create economic opportunities. The phrase “defund the police” has been co-opted by opponents to frighten people, a tactic that overlooks the damage done by police violence, they say.

“You’re not going to take away police tomorrow and then have someone breaking in their window,” Angela Waters Austin, a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter chapter in Lansing, said. “That’s a false narrative that uses fear to control people so they demand police get more money.”

‘New priorities’

In the days after Floyd’s death May 25, people swarmed the streets of Lansing to protest police brutality and systemic racism, part of the national movement that rallied around chants to “defund the police.” The city is 61 percent white, 23 percent Black, 14 percent Hispanic and 4 percent Asian American; its police force is 75 percent white, and 14 percent Black, 7 percent Hispanic and 4 percent Asian American.

The protesters also aired grievances about local law enforcement. Black Lansing residents have complained that police disproportionately pulled them over for traffic stops. Studies commissioned by the police department have found no evidence of racial profiling. But an analysis in July by the Lansing State Journal newspaper found Black people were nearly twice as likely to be stopped as white people.

Protesters also recalled a 2019 incident in which an officer was caught on video punching a 16-year-old Black girl while trying to arrest her for probation violations; the officer served a brief suspension and the girl pleaded guilty to resisting arrest.

On May 31, the second day of Floyd marches in Lansing, police used pepper spray against protesters they said had turned destructive. Activists said the move helped prove their point that police were too quick to use force and deserved a funding cut.

The demand split Lansing’s nonpartisan City Council, and when Schor, who is white, refused to consider reducing the police budget, activists called on him to resign. He later announced a series of initiatives that included an end to traffic stops for minor infractions and the creation of a diversity task force.

Activists said that didn’t go far enough. They backed a city councilman’s proposal to cut the police budget by 50 percent over five years.

That money, they said, should go toward improving residents’ lives and alleviating conditions that cause people to break the law. They called for more investment in mental health services, addiction services, affordable housing, education and job opportunities, the elimination of food deserts, and violent-prevention programs that aren’t run by the police.

“We’re talking about a new set of priorities for the city based on what the community needs,” said Sean Holland, a Black pastor and community organizer. “It has nothing to do about hating the police. It’s about setting city priorities and adjusting the budget accordingly to reduce the harms perpetuated for generations on Black and brown people.”

Then, Lansing began to see a spike in shootings, part of a nationwide trend that peaked in the summer of 2020 but is continuing in many cities. Green warned that budget cuts would force layoffs in his 198-officer department. He pointed to a rise in crime that followed budget cuts in 2011.

“We paid for it dearly,” he told the State Journal in August.

A majority of the council rejected the proposal to cut the police budget, saying they were concerned that having fewer officers would lead to more crime.

“The defunding of the police in itself does not address racism, systemic racism,” Councilwoman Patricia Spitzley, who is Black, said in a recent interview.

“To just arbitrarily reduce the police budget by 50 percent without a study of the ramifications or what to do with the money was not something I was in support of. A transformation of how we do policing, I’m in favor of.”

For more of NBC News' in-depth reporting, download the NBC News app

The local chapter of the NAACP said it, too, opposed cutting the police budget.

Many of those who disapproved of cutting the police budget were scared of the idea of having fewer officers around, said Randy Watkins, the chapter’s vice president and a member of two task forces examining ways to improve racial justice and diversity.

“I think most of the residents would like to see some change to how the police department operates, but when you use the word defunding, it turns people off,” he said.

The split in Lansing reflected a divide across Michigan, and the United States, over police reform, and whether police budgets should be slashed. An Ipsos/USA Today poll this month found that support for cutting police funding has dropped since the summer, with a majority of Americans against it.

Instead of backing cuts to the police budget, the Lansing City Council in September proposed increasing the number of social workers who accompanied officers on calls related to homelessness and mental health emergencies.

But police critics, including some council members, kept pressing for cuts. Soon, they had new developments to advance their cause.

More scrutiny

The first came in October, when the family of a man who had died in the city jail in April sued the police, accusing them of killing him during a struggle and then trying to cover it up.

The shackled man, Anthony Hulon, had been arrested on a domestic violence charge and had methamphetamine in his system when he began fighting with officers, officials said. Video from a jail camera showed the officers pinning Hulon, who was white, to the floor and showed him saying, “I can’t breathe” — echoes of Floyd’s last words.

A medical examiner ruled Hulon’s death a homicide. The Michigan Attorney General’s Office launched an investigation, which is ongoing. The officers returned to work; Green said he will wait to decide on discipline until after the criminal probe is completed.

A few weeks after the filing of the jail lawsuit, Lansing officers were captured on video hitting a Black man they were trying to arrest while responding to a street fight. The confrontation drew national attention. Green put three officers on leave; this month, prosecutors said they would not file criminal charges against them.

Black Lives Matter Lansing said both videos served as reasons to cut police funding.

“More police don’t make our communities safe,” Austin said.

The council took up a second proposal that called for finding “a significant reduction” to the police budget and investing that money into other programs. Again, a majority of the council declined to support it. They sent it back to a committee for changes, and it has remained there.

‘We feel the pressure’

Violence, meanwhile, continued to rise in Lansing.

By year’s end, the number of homicides hit 21, up from 13 the year before. Green vowed to lean on the violent crime task force, formed a decade ago in response to an uptick in fatal shootings — including that of Edmond’s daughter — to take illegal guns off the streets and interrupt retaliatory gun attacks.

Schor, who will present his budget proposal to the council in late March, said he wants to direct more money to social service programs that can help reduce crime and 911 calls, and follow the guidance of his racial justice task force.

“We want to make sure police behave the right way. But we also want to make sure we’re getting safety,” he said.

With police budget cuts on indefinite hold in the council, activists have pivoted to a long-range strategy that includes holding public forums on how the people of Lansing want to change the criminal justice system, Holland said. That will culminate with their own budget recommendations.

Activists say they plan to make the police budget a campaign issue. This is an election year in Lansing, with Schor seeking another four years in office. Spitzley recently announced she would run against him. Three council seats are also up for grabs.

The City Council, meanwhile, is exploring other ways to reduce the city resources that flow into the police department. That might mean not replacing retired officers, or closing the city jail.

Brian Jackson, a Black city councilman and a public defender, has proposed removing from the city books several petty crimes, including loitering and “willfully annoying another person,” which can be used as pretexts by police to target the poor and people of color. He is also part of an effort to examine other sources of funding to the police, including grants from federal and state governments.

“The fact we even scrutinize this ‘free money’ shows that as elected officials and city leaders, we hear the calls and we feel the pressure, and some of us at least are open to finding a resolution that accounts for reimagining policing here,” Jackson said. “Before last year, there wouldn’t have even been any discussion.”

Green said the situation has forced him to plead with the council to approve items — a grant to pay for an auto theft investigator, a widow’s donation to his K-9 unit — that he never imagined would be at risk.

“I do see that as an element of defund,” he said. “That is a nuance of it that has people on the City Council saying, ‘No matter what, we don’t want to see the police department get a dime.’”

Green’s appeals have worked. So far, his department hasn’t lost any money.