Houston generally gets about 50 inches of rain a year, at least before Hurricane Harvey came to town. Normally it takes 104 days of rain to get that much moisture, so no one could have imagined that much falling in just a few days.

No one, that is, except America’s principal computer weather-forecasting system. And a bunch of meteorologists, who issued sharp warnings of the disaster to come.

The alert from the Global Forecast System (GFS) of the potential for a seemingly unthinkable 50-inch downpour arrived in meteorologists' computers on Aug. 23 — two full days before Harvey roared ashore. The prediction went out almost immediately, starting with climate scientist Ryan Maue of WeatherBell Analytics, who tweeted: “Exact amount unknown, but this ballpark extreme value rings alarm bells #Harvey.”

Though forecasters hedged a bit from the largest possible totals, they left little doubt about the impending threat. That same morning, a Wednesday, AccuWeather, a consultant to businesses and media, warned of possible “life-threatening" floods. The Washington Post’s weather blog foreshadowed how the deluge would linger: “Harvey will stall over the Texas-Louisiana area through most of the weekend.” Al Roker of NBC News warned of "a major flooding event." By the next day, the network predicted 30 inches of rain.

The ability of weather forecasters to nail the magnitude of the threat posed by Harvey days in advance was seen as a marked improvement in the forecasting business, one that is being celebrated in their close-knit community. They did a particularly good job in plotting the track of the storm and its rainfall potential, which have traditionally been among the most difficult tasks for forecasters.

But as the devastation from the storm became a reality, meteorologists raised other important questions: Could their warnings have been even stronger? Is more imagination (or virtual reality?) needed to penetrate the public consciousness? And why didn’t public officials do more?

"Can they adequately sift through all the sources and all the information to find the critical risk information they need?" asked Gina Eosco, a social scientist and risk communication expert who advises the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). She will study the Harvey response to see how officials might do better the next time.

At the outset, meteorologists took at least a moment to appreciate the work they accomplished. The meteorologist forecasting community as a whole did a very good job in warning people about this storm," said Joel Myers, founder of AccuWeather and an elder of more than half a century in the weather foreshadowing business.

Myers said his company uses 156 sources from around the world, including several that rely on artificial intelligence, to hone predictions. And some of those tools have been sharpened immensely, particularly since Hurricane Andrew devastated Florida a quarter century ago.

In 1992, modeling a hurricane’s track was only reliable three days in advance, as National Geographic recently reported. But two recent modeling innovations have allowed more precise forecasting, going back as much as five days. The average error on mapping the course of a storm has improved markedly too — the average error was reduced over the same 25 years from 270 miles to about 90 miles, the magazine reported.

One of the those new computer models, HWRF (which stands for Hurricane Weather Research and Forecasting), has sharpened short-range projections, according to Jason Samenow, The Washington Post’s weather editor and chief meteorologist for the paper's Capital Weather Gang blog.

“That is another tool in the tool box,” Samenow said, “and yet one more piece of data that allowed us, by Thursday or Friday, to know that Harvey would be a severe event.”

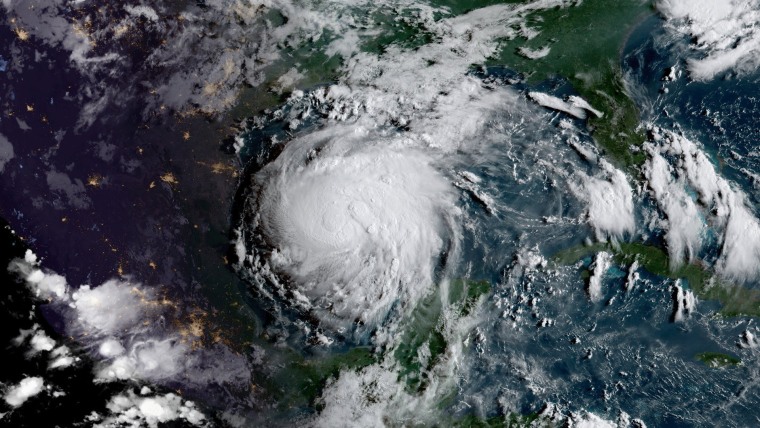

One of the most challenging aspects for meteorologists remains predicting intensification — when a tropical depression will turn into a storm, then a hurricane, and a hurricane that might escalate through categories 1 to 5. The launch of a new weather satellite, the GOES-16, in November of last year has helped all forecasters track storms minute by minute with extreme high-resolution images, said NBC News meteorologist Sherri Pugh.

NBC also employs the Ensemble computer modeling system, which runs a series of models for a single storm, each with slightly different variables. That capability was particularly important in the case of Harvey, Pugh said, because the predicted rain was so intense that forecasters using only a single model might have doubted the data.

A week out from Harvey’s landfall, forecasters knew the storm could make a turn into the Texas Coast. Five days out, they knew flooding was a possibility. Three days beforehand, AccuWeather forecast as much as 16 inches of rain in Houston. And NBC meteorologist Bill Karins tweeted about the possibility of a "dump" of up to 18 inches.

Then came a quickening cascade of ominous reports. Two days before Harvey hit, the Hurricane Center warned: “Rainfall from Harvey could cause life-threatening flooding.”

Samenow, the Washington Post’s meteorologist, said that while his profession performed admirably leading up to the disaster, it still may not be as bold in its messaging as improved forecasting would warrant.

“Our tools are good enough now that, when there is a level of agreement that we had in this instance, we have to have the institutional awareness to let people know the severity of the risk,” Samenow said. “Most people did sound the alarm, but whether... that was unified and strong enough, there’s still some question about that.”

Relying on improved science now, the profession needs to make clear when it is not just speculating, but is convinced trouble is on the way, he said. The profession had that conviction with with Harvey.

“We need to have the confidence and awareness to pull the trigger and convey the severity and urgency of the situation and try to avoid equivocation,” Samenow wrote on the paper's blog.

“We need to have the confidence and awareness to pull the trigger and convey the severity and urgency of the situation and try to avoid equivocation,” Washington Post Weather Editor Jason Samenow.

Eosco, the risk communication consultant, said she was worried about how such messages are received by a public bombarded in a 24/7 media culture.

"Can people on the ground sift through ALL the information to find the relevant information they need?" she asked, via email. "Which pieces of information do they hear?"

Eosco wondered whether virtual reality and augmented reality technology might help in "making hazards appear more concrete in reality may make the risk more believable."

Some governments, including in Iowa, already utilize tools like a flood-map simulator that help people visualize what an inundated landscape would look like. Media outlets, including the Weather Channel, face one of their "biggest challenges" in adequately conveying the threat, said Mike Chesterfield, director of weather presentation for the Weather Channel, which is partly owned by NBC News parent NBCUniversal.

"The complication is that it is still impossible to produce a visualization on what that flooding will look like on a street-by-street basis," said Chesterfield. "The future of flood forecasting will likely combine high-resolution modeling capability which will yield inundation maps at street level."

But Myers, of AccuWeather, said it is not the messengers who need to do more. He called it “unconscionable” that Houston and other communities were not evacuated, given the warnings issued.

Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner and the administrator of surrounding Harris County rejected such arguments, saying that the exact areas that would flood were unknown and that mass evacuations in a metropolitan area of more than 4 million people would come with considerable risks.

Turner pointed to Hurricane Rita in 2005, which killed 120 and left $12 billion in damage. An analysis afterward found that a mass evacuation of roughly 2.5 million Houstonians gridlocked freeways for nearly 24 hours and may have resulted in the deaths of almost as many people as the storm.

The mayor tweeted on Friday: "Chaotic 2005 traffic with Hurricane Rita lurking was tragic. No official has issued evac order for Houston now. Calm and care! #Harvey.” On Sunday, he defended his decision to keep Houstonians at home.

"One, if you can recall, there was a lot of conversation about the direction in which Hurricane Harvey was going to go," Turner said. "No one knew which direction it was going to go. So it's kind of difficult to send people away from danger when you don't know where the danger is. Number two, that kind of evacuation in a couple days — the logistics would have been crazy."