In the nearly year and a half that Courtney Hall has been with Housing Up, a Washington-based nonprofit that helps families secure affordable housing, the number of people seeking aid has jumped, he said — even as the district's population of homeless families declines.

But Hall worries that the families who rely on rental assistance from the Department of Housing and Urban Development might wind up on the streets under a Trump administration proposal.

Under the proposal, which would require congressional approval, about 2 million federally subsidized households across the country would immediately see their rents raised by roughly 20 percent, according to an analysis released Thursday by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning think tank that focuses on reducing fiscal inequality.

"If folks can't afford to make up the difference, we are going to see an increase in those who are homeless," said Hall, Housing Up's vice president of programs. "These families are already teetering. They're not just splurging and spending money — they're doing what they can to make ends meet."

Housing Secretary Ben Carson views the idea of getting tenants to pay more toward their rents as a way to prod them to find work or earn higher incomes.

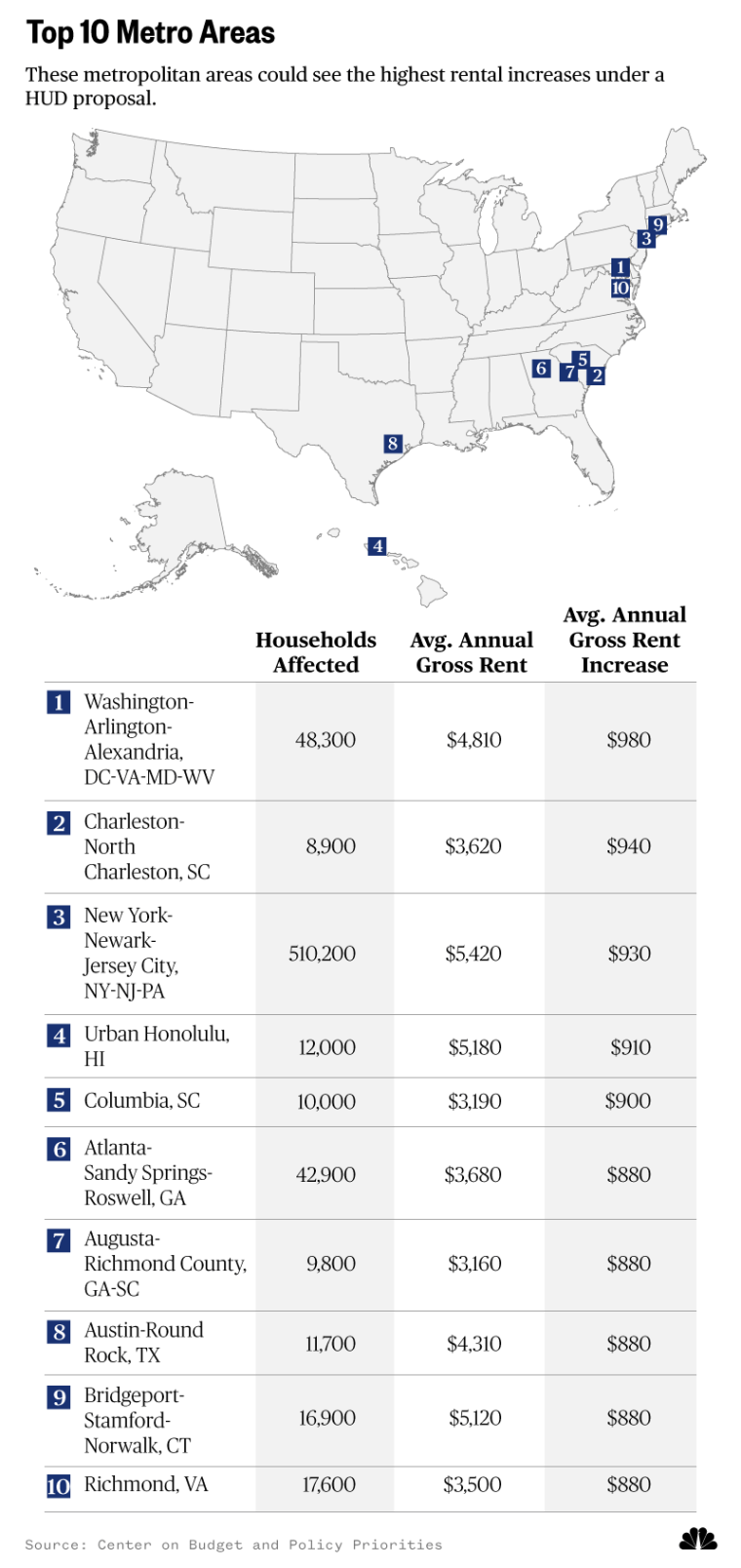

In the nation's capital, the rental increase could translate to an extra $980 a year on top of the average annual gross rent of $4,810 for a federally subsidized apartment. That would be the largest increase for the top 100 biggest metropolitan areas in the country, the policy center found.

Advocates and housing officials in other cities share similar fears.

In Charleston, South Carolina, where most households could see a 26 percent rise, or $940, in average annual gross rent, the head of the local housing authority called the proposed HUD increases "catastrophic."

"We'd lose a lot of people within a very short time: the ones with the smallest pocketbooks, the least discretionary income," Donald Cameron, president and CEO of the Charleston Housing Authority, told The Associated Press. "What do they do? If you take away that safety net, they're in free fall. Where do they go?"

At an event in Detroit on Thursday, Carson said the proposal is the result of budget constraints. But the plan could change, he told reporters, based on funding for the agency, adding that HUD has already begun working with Congress.

"The reason that we had to even consider rent increases is because we're working with a specific budget," Carson said. "And in order not to have to raise rents on the elderly and the disabled or to displace people who are already in programs, that was the only option."

During a recent phone interview with Fox News, Carson dismissed Democrats who said the plan is an "example of the Trump administration's war on poor people."

"I would say it's just the opposite," Carson said. "It is our attempt to give poor people a way out of poverty."

But Hall isn't so sure.

"Somehow you increase rent and magically inspire people that they'll get off the couch and do work?" he asked. "Many of our clients want to work, and the vast majority do."

The problem, he added, is that cities such as D.C. already have high rental costs from gentrification and few affordable-housing options, and offer minimum-wage jobs that don't allow for families to save for their futures.

A HUD spokesman said the proposal is merely the beginning of an "important conversation" — not the end.

HUD's initial proposal includes delaying rental increases for elderly or disabled households for six years, and changing the requirement that rental assistance recipients recertify their incomes each year to every three years instead. That would reduce paperwork for recipients while giving them a chance to increase their incomes, officials say.

"HUD-assisted households are now required to surrender a long list of personal information, and any new income they earn is 'taxed' every year in the form of a rent increase," Carson said in a statement in April, when the agency announced its Make Affordable Housing Work Act.

The bill would increase the rent for families who get rental assistance to 35 percent from 30 percent of their monthly income, and would raise the minimum rent to $150 from $50 per month. The proposal would eliminate deductions for medical care and child care, and for each child in a home. Currently, a household can deduct from its gross income $480 per child, significantly lowering rent for families.

Will Fischer, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, questioned the timing of the rental increases, which haven't occurred on such a large scale since 1981. The increases would come on the heels of the $1.5 trillion tax cut approved last year by President Donald Trump that benefits corporations and top income earners.

Fischer said HUD should instead be focused on implementing reforms that Congress passed in 2016 that would allow more housing authorities to determine their own policies for how tenants can increase their incomes.

The current proposal, he said, means "big rental increases that would fall on low-wage workers and seniors, and they will have to divert money from other basic needs like school supplies and medicine."

"You're making these people vulnerable to eviction," he added.

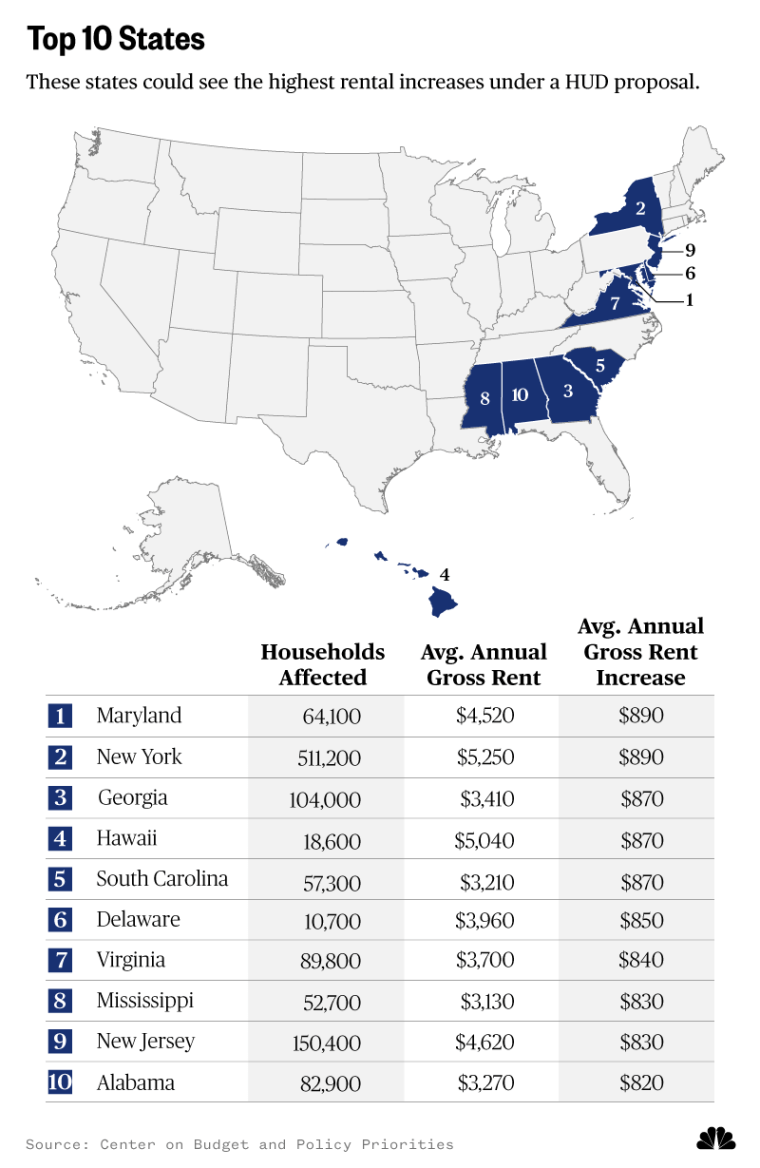

CORRECTION ( June 11, 2018, 12:20 p.m. ET): An earlier version of this article included a map that incorrectly labeled the states of Mississippi and Alabama. The map has been replaced.