The story is eerily familiar.

A college student eager to make new friends and find a community decides to pledge a fraternity. To gain entrance, he has to suffer through a series of hazing rituals. One night, he is forced to binge drink, getting blackout drunk. By morning, he's dead.

His family is devastated. His hometown mourns. The college calls it a preventable tragedy and says it might start a committee to investigate hazing. The national fraternity chapter categorically denounces the practice.

The parents appear on TV; through tears they say how greatly they will miss their son. He was their light. He had so much ahead of him. The coverage dies down, but the grief remains for those closest to him. Eventually, the community forgets — until it happens again.

And it always happens again.

Since 2000, there have been more than 50 hazing-related deaths. The causes are varied — heatstroke, drowning, alcohol poisoning, head injury, asphyxia, cardiac arrest — but the tragedies almost always involve a common denominator: Greek life.

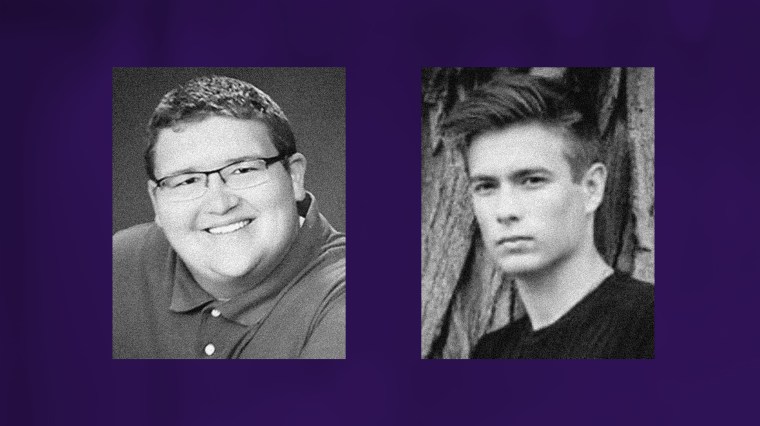

On Feb. 27 and March 7, two more names were added to the abject list: those of Adam Oakes and Stone Foltz.

Oakes, 19, was a freshman at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. The evening before he died, he was matched with a "big brother" at Delta Chi. His family alleges that his death was due to hazing, NBC Washington reported. He passed out after drinking, and when friends found him facedown on the couch, half his face was purple, his cousin said. His father told reporters he is left with a "hole in my heart that will never be sealed." The cause of death hasn't been officially determined.

Foltz, 20, a sophomore at Bowling Green State University in Ohio and a new member of Pi Kappa Alpha, died in what his family’s attorney alleged was an off-campus hazing incident involving alcohol. His parents donated his organs "so that others may have a second chance at life."

Their deaths have renewed calls for Greek life reform, but the question remains: Can fraternities exist without hazing? And if not, will the deaths ever stop?

VCU prohibits hazing. So does Delta Chi, the fraternity Oakes pledged. After his death, both the school and the fraternity offered their condolences.

Oakes wasn't the first Delta Chi member or pledge to die after being hazed. In 1994, Terry Linn died after he pledged the fraternity's Bloomsburg University chapter in Pennsylvania on "hell night." Linn transferred to the university just four months before his death. His mother said he pledged because he was searching for belonging.

At the time, a Bloomsburg University spokesperson said the school needs "to do a better job of educating our students about the dangers of alcohol and their responsibilities."

Ten years later, another Delta Chi fraternity member died, this time at New Mexico State University. Steven David Judd, the president of his local chapter, died after a night of heavy drinking.

Judd's family said in a statement after their son died in 2004 that they "hope that Steven's untimely death will be a learning experience for others."

Delta Chi declined to comment on what it has learned from the deaths and wouldn't say what changes it might make in the wake of Oakes' death, pointing to previous statements insisting that it doesn't tolerate hazing.

VCU President Michael Rao said he wants to make certain none of his students ever again dies from hazing.

On the phone, Rao sounded shaken by Oakes' death. "This has put a bigger knot in my stomach than I have ever experienced," he said.

The school said it suspended new member intake for the entire Greek system and is making all fraternity and sorority members undergo new anti-hazing training immediately.

"If Greek life exists, it must exist at the highest standard, and it must change," Rao said when asked whether he has considered abolishing the Greek system.

He's concerned about hazing, alcohol, drugs and sexual violence in the organizations. For now, the school is focusing mainly on reform measures.

Jonathan Zimmerman, a professor of the history of education at the University of Pennsylvania's Graduate School of Education, remains skeptical that reform can work.

"Hazing is illegal in almost every state, and nobody gives a s---," he said. "Just because you ban it doesn't mean it goes away.

"I don't see how we have fraternities without hazing, because fraternities exist to define and protect a kind of masculinity. Without hazing, how would they decide who is a real man?" he said.

After co-education began on most campuses, fraternities went from being institutions meant mostly to reinforce and protect class distinctions on campus to also "becoming a primary way that young men define themselves as men," he said.

In that way, said Nick Syrett, a professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at the University of Kansas who has studied the history of Greek life, hazing is a literal test of the male body to prove masculinity.

"It bonds the people who are being hazed," Syrett said, "and it is also a way for the members to make pledges earn their place in the brotherhood."

While fraternities condemn hazing when tragedy strikes and insist that it isn't part of their ethos, "many fraternities have demonstrated this is fully in keeping with exactly who they are," Syrett said.

Judson Horras, president and CEO of the North American Interfraternity Conference, rejected that characterization.

Horras said the deaths of Oakes and Foltz were "terribly tragic and senseless." He said he sees a solution in stricter laws and further criminalization. Hazing, Horras said, is a problem in all aspects of college life, not just in fraternities, and college students often die from alcohol use unrelated to Greek life. Comparing the problem to drunk driving, he said he is certain that if the penalties for hazing are strengthened, the hazing rates will drop.

"The students in both of these cases who did this didn't do it at the fraternity house. They did it at their individual properties. I guarantee you … they were told not to do this by the university, they were told not to do this by the national fraternity. They went out on their own and broke policy," he said. "They need to publicly be held accountable, they need to be expelled from school, and everyone needs to see that as an example."

Horras said he believes students are unafraid to break the rules because the punishments rarely lead to criminal prosecution.

Yet the death of Foltz may provide a foil to Horras' argument. Foltz was pledging Pi Kappa Alpha when he died. In 2015, 22 former members of the fraternity were convicted on hazing charges in the 2012 hazing-related death of Northern Illinois University student David Bogenberger.

At the time, DeKalb County State's Attorney Richard Schmack said it was the largest hazing prosecution in U.S. history.

Pi Kappa Alpha declined to comment on how it has changed since Bogenberger died, and prosecutions in the death of Bogenberger didn't save Foltz.

Zimmerman compared hazing laws to speed limits.

"You can say you can only drive 55 miles per hour on I-95 and most people don't do that," he said. "I'm not against these hazing laws any more than I'm against speed limits. A speed limit might reduce speeding, and a hazing law might reduce hazing. On those grounds, it's defensible, but we can't kid ourselves it will eliminate hazing."

That's why students on many campuses have said they've had enough of fraternities altogether, calling for the abolition of the system. Last summer, virtual anti-Greek movements swept universities across the country, calling out the organizations not only for hazing but also for racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and classism.

Yet the power the Greek life wields on campuses makes that a difficult proposition, Syrett said.

Universities fear alienating alumni donors, many of whom hold deep ties to fraternities and sororities, if they come down too hard on Greek life, Syrett said. Schools also rely on the organizations to provide housing and socialization.

Horras, of the North American Interfraternity Conference, insisted that the organization can break the cycle and defeat hazing.

When asked whether he was hazed during his time in a fraternity many years ago, Horras said that he was.

"You know, I had an experience that wasn't ideal."