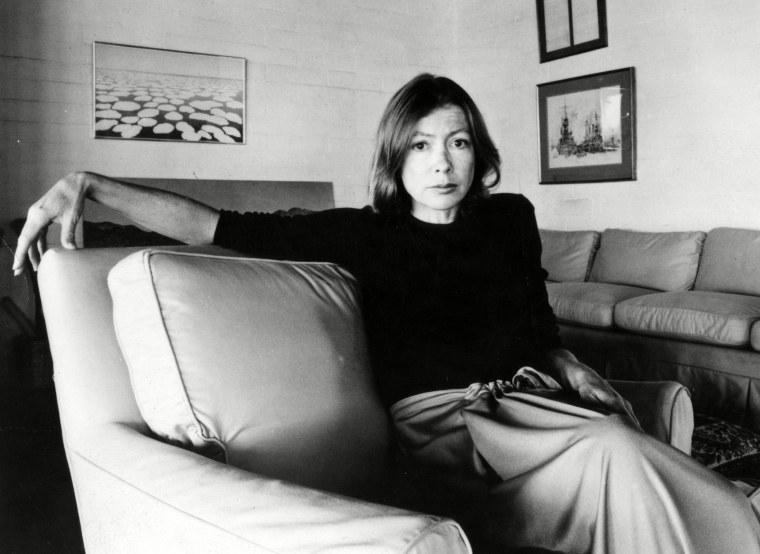

Joan Didion, the sharp-eyed and cool-headed journalist, essayist and novelist who chronicled the social upheavals of the 1960s, the cultural landscape of California and the inner struggles of grief, died Thursday at her home in New York.

She was 87.

The cause was complications from Parkinson's disease, Penguin Random House said in a statement.

“Didion was one of the country’s most trenchant writers and astute observers. Her best-selling works of fiction, commentary, and memoir have received numerous honors and are considered modern classics,” it said.

She rose to prominence in the 1960s as one of the pioneers of "New Journalism," marrying traditional reporting techniques to literary flair and first-person experience. She cultivated a devoted following with cool, unsparing explorations of American politics, Hollywood, the counterculture and the contradictions of the Golden State.

Didion's best-known works include "Slouching Towards Bethlehem" (1968), a collection of essays about the turbulence of the late 1960s, and "The Year of Magical Thinking" (2005), an account of the grief that followed the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne.

"The White Album" (1979) is a classic of literary journalism, effortlessly blending the conventions of cultural criticism, memoir and nonfiction storytelling.

The title essay is a veritable tour of California in the '60s — Black Panther Party meetings, a recording session with The Doors — as well as an inward-looking record of the author's psychological struggles.

The opening line became synonymous with Didion and her worldview: "We tell ourselves stories in order to live."

She was a frail woman, even in her youth, but she used her size to her advantage, saying: "I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.”

Didion was born in Sacramento in 1934 and graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1956. She then moved to New York, where she started working for Vogue and launched her career as a professional writer.

She published her debut novel, "Run, River," in 1963. The following year, she married Dunne, a novelist, screenwriter and literary critic who became her most important creative partner.

Didion and Dunne relocated to California, where they adopted a daughter, Quintana Roo, in 1967. They were virtually inseparable collaborators, working together on screenplays for films like "The Panic in Needle Park" (1971) and "Up Close and Personal" (1996).

Didion's second novel, "Play It as It Lays" (1970), was an unsentimental dissection of Los Angeles in the '60s, tersely but memorably uncovering the despair creeping underneath the glamour of the Hollywood dream factory.

Didion and Dunne later collaborated on the screenplay for a 1972 film adaptation of "Play It as It Lays," starring Tuesday Weld and Anthony Perkins.

But for all of her gifts as a novelist, Didion may be most remembered for her elegant, incisive contributions to the New Journalism movement, which also encompassed the work of Tom Wolfe, Nora Ephron and Gay Talese.

She was a clear-eyed observer of events both past and present, narrating the vagaries of hippie culture to the kidnapping of Patty Hearst with a cool detachment and quiet intensity.

“Joan was a brilliant observer and listener, a wise and subtle teller of truths about our present and future. She was fierce and fearless in her reporting. Her writing is timeless and powerful, and her prose has influenced millions," Shelley Wanger, her editor at Knopf, said in a statement.

Didion was consumed with the tangled history of her native California — "a hologram that dematerializes as I drive through it," as she once described the state.

“California belongs to Joan Didion,” the New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani wrote in 1979. “Not the California where everyone wears aviator sunglasses, owns a Jacuzzi and buys his clothes on Rodeo Drive. But California in the sense of the West. The old West where Manifest Destiny was an almost palpable notion that was somehow tied to the land and the climate and one’s own family.”

She rejected official narratives and sanctioned histories, presciently casting doubt on the public assumptions around the so-called Central Park jogger case of 1989. (The convictions of the five Black and Latino men tried in the case were later overturned, and they were released from prison.)

Didion's later years were partly defined by reckonings with loss and grief.

"The Year of Magical Thinking" told the story of the pain that followed Dunne's death in 2003. He collapsed at their table and died of a heart attack — all while their daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne Michael, was hospitalized with a serious illness.

Quintana died at age 39, not long after the book was published, from acute pancreatitis. Didion explored the emotions of her daughter's death in "Blue Nights," published in 2011.

“We are not idealized wild things," Didion wrote in "The Year of Magical Thinking."

"We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.”

Didion's other notable works included three more novels — "A Book of Common Prayer" (1977), "Democracy" (1984) and "The Last Thing He Wanted" (1996) — as well as several nonfiction collections, including "Salvador" (1983) and "Political Fictions" (2001).

In 2005, she was awarded the American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Belles Lettres and Criticism. In 2007, she was awarded the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded her a National Medal of Arts and Humanities.

"Didion has produced works of startling honesty and fierce intellect, rendered personal stories universal, and illuminated the seemingly peripheral details that are central to our lives," the citation reads.