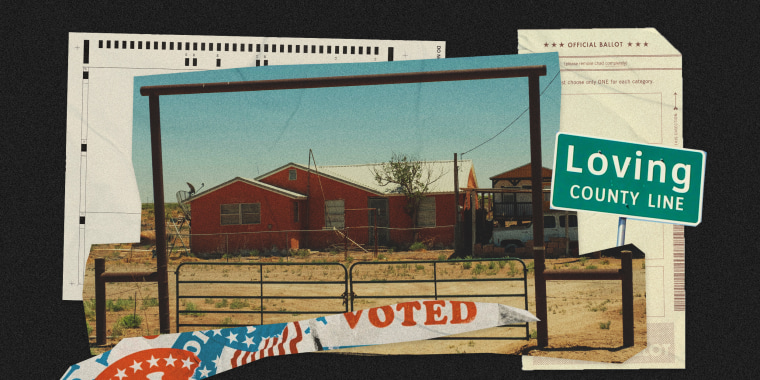

MENTONE, Texas — One of the worst-kept secrets in Loving County sits along the shoulder of a desolate stretch of state highway in the heart of the Permian Basin.

It’s a sprawling ranch with a sunbaked adobe home that the Pecos River flooded out years ago, nestled near a trailer and a mobile home on stilts, all behind a padlocked gate.

Eleven people are registered to vote at this address. One of them is Loving County Commissioner Ysidro Renteria, who has been in office since 2011 and listed this property in December as his permanent address on his application to run for re-election, signed under oath. He and at least three relatives used the address to vote in the March primaries.

The secret?

“No one lives there,” Loving County Sheriff Chris Busse, who also serves as the registrar of voters, said in May. “I can attest that I’ve been here since 2008 and there has never, ever, ever been any of the Renterias — not even Ysidro — occupying it.”

The old Renteria farmhouse is hardly the only open secret in this county, the least populated in the continental U.S. Voter registration has been suspiciously high for generations, driven by bitter feuds among a handful of prominent families fighting for control of the local government. The voter registration roll is 97 people long, according to the Texas secretary of state, but the U.S. Census Bureau estimates only 57 people live here.

Elections often come down to tiny margins, but the stakes are high: Winners are awarded sway over an outsized budget. This roughly 670-square-mile patch of desert sits atop some of the richest oil and gas reserves in the U.S., generating a tax base that has hovered around $7 billion to $9 billion. Salaries for top elected officials are in the six figures. They steer an annual budget of more than $28 million.

Renteria and his family have benefited from Loving County taxpayers. Renteria earns about $55,000 a year for the part-time job of commissioner. His half-brother and nephew’s trucking company has earned more than $4.7 million doing road maintenance for Loving County since 2015, county payment records show.

Loving County’s long history of rancorous politics has generated allegations of voter fraud dating to the 1940s, but a new state law and frustrated local officials have put the county’s out-of-town voters in the crosshairs. Renteria is now under investigation by the state attorney general’s office. A justice of the peace recently ordered him and three other people who showed up for jury duty hauled off to jail for allegedly not living in the county.

Renteria, the descendant of a longtime farming family, owns a ranch with a 2,500-square-foot home in neighboring Reeves County, about a half-hour drive away. Since at least 2011, when he became a commissioner in Loving County, he has claimed a homestead exemption on the home in Reeves County — a tax break afforded to Texas taxpayers on their “principal residences,” records show.

Texas election code requires candidates for commissioner to continuously reside in the county they plan to represent for at least six months before they file to run for office. Applications are submitted under oath, with the possible penalty of perjury.

The sheriff said someone (not him) filed a complaint with the Texas attorney general’s office saying Renteria doesn’t live in Loving County. NBC News filed a public information request seeking a copy of the complaint from the attorney general’s office, but officials withheld it, citing “an active criminal investigation being conducted by the OAG’s Criminal Investigations Division.”

Renteria, 61, declined to speak with a reporter and didn’t respond to written questions. His lawyer didn’t return phone calls.

For generations, descendants of politically powerful families have cast their ballots here, despite having moved away decades ago in search of other opportunities. They have chased their dreams to big cities like Amarillo, Lubbock and Odessa, building careers and raising families hundreds of miles from this county’s only town, Mentone, population 22.

In the March primary election, 1 in 5 voters in Loving County had homestead exemptions elsewhere in Texas, an NBC News analysis of tax and voter records shows.

It’s a bitter pill for some who live in Loving County, where there’s no school, no supermarket, no bank and no barber.

Busse, a 22-year Air Force veteran, said it’s easy to pick out unfamiliar faces at the old courthouse on election days. “They have a voter card,” he said. “But the only time you see them is when it’s time to vote or at the annual Christmas party.”

For years, Busse said, there wasn’t much he could do about voters who didn’t actually live in the county. Texas voter residency law was loose, allowing people to vote in places they didn’t live but intended to return to someday, so long as they had homes there.

Then, last year, in the wake of former President Donald Trump’s false claims that the election was stolen, the Texas Legislature passed a law that tightened the definition of residency for voter registration. Known as SB 1111, the new law — effective Sept. 1, 2021 — says people can use “previous residences” to register to vote only if they’re living there at the time and plan to stay there. But it left in a fuzzy provision that allows people to vote in places they intend to return to — making the measure’s impact as cloudy as the brackish waters of the Pecos River.

Under the law, voter registrars can send out address confirmation cards to people they suspect don’t live in their counties, requiring them to affirm their addresses under oath before they can vote again.

That’s what Busse did in Loving County in June, mailing out 44 cards — to nearly half of the county’s registered voters — requiring them to say where they live, with a possible penalty of perjury. Some people have taken it as a “personal attack” and accused Busse of misinterpreting the law, but he said his only goal is to follow it.

The criminal investigation into Renteria and Busse’s push to crack down on out-of-town voters have added fresh hay to an already smoldering political firestorm heading into the November election. Renteria, who is facing his first opponent since he took office more than a decade ago, is closely aligned with the reigning political family, the Joneses, who face their own challenges.

In May, Judge Skeet Jones, 71, the most powerful politician in the county, was arrested on felony charges of cattle rustling and engaging in organized crime. Three ranch hands were arrested as well; none of the four men has yet been indicted. Jones, who is running unopposed this fall, declined to comment. His attorney didn’t return calls.

Some of the politics playing out now date back to long-standing bitter rivalries between the Joneses and other prominent families. Adding to the tensions, newer residents seen as “outsiders” have been agitating for changes in how the county is run. And the politics have turned personal: Members of the Jones family are running against each other for county clerk.

Top elected official in Loving County was charged with cattle theft

- Judge Skeet Jones, the scion of a powerful ranching family, was arrested in May after a yearlong investigation.

- He was charged with livestock theft and engaging in criminal activity, accused of gathering up and selling stray cattle.

- Authorities said the investigation was ongoing.

“Everybody says politics is a blood sport,” said Steve Simonsen, the county attorney. “Well, here it is.”

‘That’s gonna weed out some voters’

State Sen. Paul Bettencourt, a Republican from Harris County who sponsored SB 1111, said the law’s intent was simple: “to get people to register where they live.” But it was also limited in scope.

Bettencourt introduced the legislation after he said he learned that about 4,800 voters in Harris County had registered to vote using UPS store P.O. boxes as their addresses. He wanted to eliminate the use of “impossible,” uninhabitable addresses.

The law also states that no one can use a previous residence to register to vote “unless the person inhabits the place at the time of designation and intends to remain.”

When Busse read the law, he thought, “Well, that’s gonna weed out some voters in the county, because you can’t continue to claim a residence in another city and then come out here and vote,” he said.

But he had questions about how to enforce the new law as voter registrar, so he called up the Texas secretary of state’s office and spoke with Keith Ingram, the Elections Division director. Ingram’s office fields complaints about election law violations and can refer them to the attorney general’s office for criminal prosecution. Punishment is rare: The attorney general’s office has successfully prosecuted only about 155 people for election fraud offenses since 2005.

Ingram told NBC News that Busse asked about a few scenarios in Loving County, including a derelict mobile home “that nobody lives at, nobody visits, doesn’t have utilities.”

“And people are claiming that as their residence for voting purposes,” he said.

Ingram said that under SB 1111, it’s pretty clear that “if people don’t inhabit their mobile home, they shouldn’t be allowed to use it for voter registration.”

Busse also asked Ingram about voters he sees only once or twice a year. Ingram’s answer wasn’t what Busse expected. While the new law requires people to inhabit the homes where they registered to vote, it also still includes an earlier provision that allows people to register at homes that they “intend to return to,” Ingram said.

If people have property in Loving County and go back once or twice a year and spend a few days there, Ingram said, “I think, arguably, they inhabit that location, and they can claim it as a residence.”

Busse said he heard a key word in Ingram’s explanation — “arguably” — and concluded that the law isn’t entirely clear.

Ingram also told Busse that someone who largely lives elsewhere for decades could consider that a “temporary absence.”

“‘Temporary’ can be the 30 years of my legal career if I intend to retire back where I grew up,” he said. “And I go visit a week every summer or a week in the fall, every year. Then I think that ‘temporary’ is in the eyes of the beholder at that point.”

Ingram said that if a close election resulted in a court challenge, it would be up to a judge to decide whether individual voters met residency requirements.

Otherwise, Busse’s power as registrar was limited, Ingram told him.

After the March primary election, Busse called Ingram back, frustrated. The commissioner’s race in Busse’s district, Precinct 4, had come down to an 8-5 vote.

“Three of the votes that were cast were by people who don’t live in the county. They all three live in Kermit, Texas,” more than 30 miles from Mentone, he said.

He liked both candidates, but he was upset. “That’s a situation where my vote did not count,” he said.

Ingram said there was no way to challenge the election results short of a lawsuit filed in District Court.

But there was one thing Busse could do: send out voter registration address confirmation cards. If voters don’t respond within 30 days, they are placed on “suspense,” which means they can’t vote again without making sworn statements about their residences. Someone who lies on the card can be prosecuted for making a false statement (a misdemeanor) and swearing to it under oath (a felony). The maximum sentence for the misdemeanor is up to a year in jail; the felony ranges up to two years.

In June, Busse said he and a member of the voter registrar staff drew up a list of everyone on the voter rolls they suspected doesn’t actually live in Loving County. They looked at voters who used post office boxes in other places. They also relied on their own “personal knowledge” of where people actually live and work, Busse said. The 44 cards they sent out are now trickling back into the office.

People have accused Busse of having an agenda. But that’s not the case, he said. “My only agenda is this,” he said, lifting a book of the Texas criminal code he keeps within arm’s reach on his desk.

“I don’t know yet if SB 1111 has any teeth,” he said. “But we’re going to find out.”

Bitter politicking and fraud allegations

Loving County has a long and storied history of voter fraud allegations, resulting in investigations by the Texas Rangers and contested elections that have ended up in the appeals court in El Paso.

Some people still repeat a story that the late Newt Keen, who owned Newt’s Cafe, used to tell about a boy crying on Election Day. Keen told the story to a Los Angeles Times reporter in 1993.

It went like this: “On Election Day, There was this ol’ boy a-sitting out there on the bench by the pay phone, and he was cryin.’”

“And somebody askt him, ‘Did you hurt yourself?’ And he said, ‘No, no, it’s my daddy — he’s been dead for 20 years, and he went and voted — and he didn’t even stop by to say hello.’”

Everyone in Mentone can rattle off the names of the powerful political families who warred for generations to control the local government. There are the Hoppers, who settled Loving County in the 1900s; the Creagers, who held on to top positions — including county judge — for decades; and the Joneses.

Skeet Jones’ father, Elgin “Punk” Jones, and his mother, Mary Belle, arrived in Loving County in 1953 and founded the P&M Jones Family Ranch. For 28 years, Punk Jones served as sheriff. His wife was the county’s chief appraiser for years. Skeet Jones, the oldest son, was elected county commissioner in 1992 and held the job until he ran for judge in 2006.

His brother Tom Jones ran for his open commissioner’s seat, losing by one vote to rancher Zane Kiehne. Tom Jones challenged the election results in court, leading to a two-day trial in Mentone, where voters in the precinct were questioned one by one about their residency.

Some were asked under oath about homestead exemptions in other cities; others were asked when they’d last visited Loving County and whether they planned to someday live there again.

The judge allowed some voters to stay on the rolls even though they had homestead exemptions in other cities if they provided convincing evidence that they someday planned to return to Loving County. But others were struck for living away for decades, even if they visited.

One of them was Tom Jones’ brother Richard Jones, who’d admitted to living in Winkler County with his wife and children since 1979, although he also owned property in Loving County. The judge also removed several Kiehne voters, including a ranch hand who admitted that his only possessions at the home he used to vote were a change of clothes and a bottle of Crown Royal whiskey.

Ultimately, Tom Jones won.

Back then, many of the county’s roads were rutted like washboards, and residents still had to line up to get potable water dispensed from a community tank.

In the past 15 years, fracking has boomed, feeding money into the county’s coffers. The roads around town are smooth and sturdy, supporting the weight of heavy oil and gas traffic. Clean water flows from the faucets.

And the Joneses have tightened their hold on the local government. Skeet Jones’ sister is the county clerk. His cousin’s husband is the county attorney. His nephew is the constable.

Nearly a third of the people who cast votes in Loving County in March were related — by blood or marriage — to the Joneses. Adult children of the county judge, the county clerk and the county attorney cast votes here, even though they put their heads to bed most nights in Wink, Lubbock and Conroe — as far as 600 miles away.

Simonsen, 66, the county attorney and Skeet Jones’ cousin’s husband, said that is entirely legal. Simonsen has lived in Loving County for more than four years, since before he was elected in 2018. He kept his homestead exemption in suburban Houston, he said, and he returns there periodically for cancer treatment. His 24-year-old son voted in Loving County in March, he said, although he lives and works in Montgomery County.

“He is here approximately every two to three months,” Simonsen said, adding that “he has more ties to Loving County than anywhere else.”

Simonsen raised a philosophical question: “What is better in the long run, that you would vote somewhere that is important to you and where you have deep ties? Or somewhere that you are just because your work takes you there?”

Mozelle Carr, the county clerk and Skeet Jones’ sister, said that although she and her husband own properties outside of Loving County, they have survived two court challenges to their residency there. Her daughter, Catherine Carr, 43, sent a letter to NBC News saying she has rented a home in Lubbock for years on a month-to-month basis but also owns property in Loving County.

Catherine Carr said there’s not much work in Loving County for psychiatric nurses. “While I make an adequate ranch hand, I am far better at alcohol detox and suicide assessments.”

She was baptized in the Pecos River by her grandfather, she said, adding: “I care more about every road, river and rock there than I do any other place in Texas.”

And she plans to vote there in November, she said, to support her mother. Mozelle Carr is facing a challenge from her nephew’s wife. “No one will doubt where I live when I do,” Catherine Carr said.

‘Y’all are picking on me’

The story behind the old Renteria farmhouse stretches back to the 1940s, when Renteria’s grandfather arrived from Mexico, determined to farm an arid patch of desert near the New Mexico border. Renteria’s grandparents had 13 children and sustained the farm for decades, passing it down to Renteria’s father.

As farming failed, the Renterias entered politics. Seledonio Renteria, Ysidro Renteria’s father, was a constable. Jose Renteria, Ysidro’s brother, served alongside Skeet Jones as a county commissioner. Ysidro replaced Jose about a decade ago after Jose stepped down.

Jose Renteria, 66, voted in the Loving County primary in March, although he has a homestead exemption in Odessa, about an hour-and-a-half drive away, according to public records. Two other relatives registered at the farmhouse on State Highway 302 also had homestead exemptions outside of the county. (None of Ysidro Renteria’s relatives returned phone calls.)

In addition to serving on the commissioners court, which has a six-month residency rule, Ysidro Renteria also holds an appointed position on the Loving County Appraisal District board, which — under Texas tax code — has an even more stringent residency requirement: two years.

At a March meeting after the primary, members of the appraisal board cited SB 1111 and gave Renteria two options: resign or be removed.

“We all know you haven’t lived in the house,” board member Amber King, the county’s justice of the peace, said at the meeting, according to a recording obtained by NBC News and verified by two attendees.

“We have to do things the way they’re supposed to be done, and the law clearly states you have to be a resident, and you’re not.

“So you can resign from the board,” she said, “or we’re going to move forward.”

Renteria refused.

“Y’all are picking on me, simple as that,” Renteria said.

“No, we’re not,” King replied.

“Yes, you are,” he insisted.

Busse, the sheriff and voter registrar, who also sits on the board, tried to reassure Renteria. “I’ve known you for years. I have nothing against you.

“I’m not picking on you,” he added, “I just have to do what the law says.”

The appraisal board voted to remove him, but for months, nothing happened. Then Renteria was summoned for jury duty on May 25. Amber King, who presides over the local justice of the peace court, said she read the requirements for jury duty, which include being a resident of Loving County, three times. Then she held Renteria and three others — including Matt Jones, Skeet Jones’ son, who she said lives outside Loving in Wink — in contempt of court for not living in the county, sending them to the Winkler County Jail. (They were released in less than six hours.)

King said in an interview that she felt it was necessary to “maintain the integrity of the court system and not allow people to lie about being residents.”

“They could actually live out here if they wanted to,” King said. “But they don’t want to. They want to manipulate the system. We’re a small county — literally every vote counts. It’s not right how people are abusing the system by living in a gray area.”

Simonsen, the county attorney, disagreed and said he expects several lawsuits to come from the contempt order.

Matt Jones declined to comment.

When the resolution to remove Renteria from the appraisal board reached the county commissioners court in June, Commissioner Raymond King, Amber King’s husband, made a motion to remove Renteria. But no one on the court, which is led by Skeet Jones, seconded his motion. After awkward seconds of silence, the motion died.

“I’m fighting an uphill battle here,” Raymond King said. “I just want to do what’s right.”

‘What do you mean by “lives”’?

Alan Sparks, 64, is running against Renteria in the November election. A ranch manager who has lived in Loving County for 31 years, Sparks is married to a dispatcher with the sheriff’s office. It’s the first time he has run for office, he said.

“When you live in a small rural county, with not many people, it tends to get ran by certain ones forever,” he said. “And nothing against these people. I’ve known them 30 years. My kids grew up with their kids.”

“But there comes a time you need to change. I don’t know if that’s coming or not. But with me running and a few others, I think that’s got some people looking at a change. I’m hoping for my kids’ and grandkids’ sake, if they decide to stay.”

In the primary, he got four votes as a Republican. Renteria, a Democrat, got five.

Since Sparks filed for office, and word of the investigation into Renteria leaked out, there have been signs of life at the Renteria ranch off State Highway 302. A flatbed truck delivered the mobile home on stilts tucked behind the old farmhouse in January, according to video reviewed by NBC News. Water and electricity connections followed, Busse said.

“Ironically,” Busse said, “that all started happening after someone reported to the state that he doesn’t live there.”

Asked by a reporter whether Renteria lives at the farmhouse, Simonsen, the county attorney, replied: “What do you mean by ‘lives?’”

He said he’d seen Renteria’s truck there “recently,” although he couldn’t recall exactly when.

“Do I think he lives there enough to be able to vote in the county and hold the office? Yes. Do I think he lays his head there every single night for 365 days a year? No. Neither does anybody else here, even if they say they do.”

In another development, the Jones family ranch recently sold two plots of land in Renteria’s district to county employees. Renteria also deeded two plots to family members. No one had registered to vote at those addresses as of June 1, according to the secretary of state. The deadline to register is Oct. 11.

Sparks said he knows that in the end, he’s going to be outgunned.

“They’re gonna beat you every time,” he said.