It was more than a sports logo, it was a symbol.

On Monday, Washington's NFL team announced that it would change its nickname and logo, which has been long been decried as racist and dehumanizing by Native American advocates. Owner Dan Snyder had previously vowed that he would "never" change the name — but that was before demonstrators across the United States and beyond took to the streets after the death of George Floyd to protest systemic racism.

Amid the momentum of the Black Lives Matters movement, sponsors including FedEx, which owns the naming rights to the field in Maryland where the team plays and officially asked for the name change this month, increased the pressure on the franchise.

Change has been the operative word in tribal communities of late: The Supreme Court ruled on July 9 that a large swath of eastern Oklahoma remains a Native American reservation based on a treaty signed with the Creek Nation in the 19th Century. This month, there have also been legal victories for Native environmental activists in their attempts to block two major oil pipelines. Statues of Christopher Columbus, whose arrival in the New World heralded the conquest and mass murder in the eyes of many Indigenous Americans, have been toppled in several states.

In short, 2020 is shaping up to be a chapter unlike most others in American history books for Native Americans.

“I see this moment in history as a day of reckoning that Native Americans have known is ahead of us because of what we’ve endured for 20 generations of intergenerational trauma as a result of genocide," said Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians, the largest and oldest Native American advocacy organization in the country.

"This is a moment we believe that we're finally seeing the principles that this country is built upon it — equality, racial and social justice," added Sharp, who is also president of the Quinault Indian Nation in Taholah, Washington.

Of all the recent victories, scrapping the Washington team name might be the most high profile. The name, changed from the Braves in 1933 when the team was still in Boston, had an ancient legacy by pro sports standards.

Many Native American elders, however, have called the nickname a slur as offensive as the N-word. There is some debate over the origin of the word, which may have been used by Native Americans to describe their own people to French traders, but newspapers showed a more sinister use by the 1860s, when the word was used in bounties offered for scalps and skins of slain Indians. There was a market for them much the same as for animal pelts.

Unaware or unmoved by that history, supporters of the nickname have cited a 2016 Washington Post poll that found 9 out of 10 Native American respondents were "not bothered" by the term. Even now, many are expressing their outrage on social media over the team's decision.

But one of the most celebrated players in the franchise's history isn't among them.

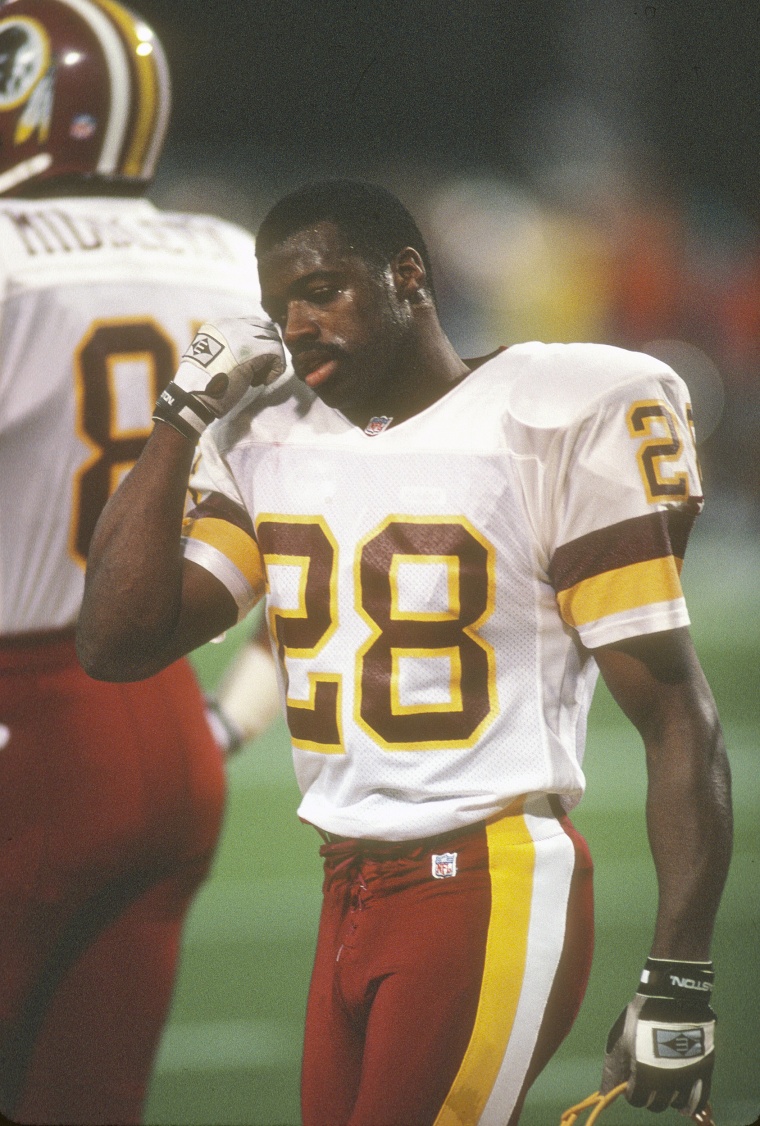

"It's a day to celebrate," Hall of Fame cornerback Darrell Green told NBC News on Monday. "It's a word that we wouldn't want if the shoe was on the other foot. It's part of this tapestry of pain and events in actions that took place in this country for many years.

"This is a wrong that is (being fixed) as a part of the reconciling of America, and I'm glad to be alive to see it," said Green, who played for the team from 1983 to 2002.

During his 20-season career, Green said he was largely unaware of the controversy over the name. But he added that several former players had told him that they could never be fans of the team because one of the original owners, George Preston Marshall, was considered a notorious racist. Under Marshall's stewardship the team had the dubious distinction of being the last NFL team to integrate a Black player, which did not happen until 1962. Marshall was also the owner who changed the team's name in 1933.

"We celebrate the chance to move forward," said Green, who is currently working with Centene Corp., a health care company, to assess the impact of COVID-19 on racial minorities and underserved communities across the U.S.

Why all this progress now? Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, a historian and the author of "An Indigenous People's History of the United States," credits Black Lives Matter protesters with including Native American causes.

"Gratitude goes from Native people right now to Black Lives Matter because they have, from the beginning of their founding, had it baked in to their whole process to defend other minorities as well," said Dunbar-Ortiz, herself a veteran activist in the American Indian Movement of the 1970s.

"There's been an uprising once the Floyd murder allowed for people’s minds to be opened. Because it really is hard for only 2 percent of the whole population to even seem to matter, much less summon some kind of energy behind it."

Dunbar-Ortiz said she hoped that the unprecedented momentum would continue — including serious reflection over the cultural appropriation in other Native American-derived nicknames in pro and college sports, such as MLB's Atlanta Braves and Cleveland Indians, the NFL's Kansas City Chiefs and the NHL's Chicago Blackhawks.

"None of those names are Native terms. They’re made up colonial terms," she said. "They’re not honoring Native people."

For the first time in memory, the drumbeat for change is not falling on deaf ears.

"To us the Washington name change signals the beginning, the first domino to fall that will lead to many more dominos falling," said Sharp, "until we do come to terms as a country with the meaning and the hurt that this activity has inflicted on our communities for generations."