Editor's Note: This is part two of a three-part series from our partners at Reuters.

CHARLESTON, West Virginia — This story has a chance of ending happily. But it begins last fall in a mangy downtown apartment as Katy Yeager, seven months pregnant, stares at a syringe and the crumpled foil that holds $40 worth of heroin.

Yeager, 24, had been clean since leaving jail eight months earlier. Initially, she was elated to be pregnant. But then the baby’s father, a former coal miner she’d met in rehab, was sent back to prison. She faced raising the baby alone.

Her final trimester was filled with insomnia, nausea and anxiety. She hated the job required by her probation — eight hours a day on her feet as a waitress at a Shoney’s restaurant. And she was desperate for money to buy a crib and diapers.

Related: Addicted Newborns: 'That Baby Is In Serious Danger'

“I just wanted to escape from myself,” Yeager recalled, “basically the loneliness, the anger and uncertainty of everything.”

Getting high is easy in Charleston, a city at the center of Appalachia’s epidemic of opioid addiction. On that fall day last year, two months before her baby was due, Yeager poured powdered heroin into a spoon, added water and held a lighter beneath it until the drug liquefied. She filled the syringe and found a vein on the palm of her hand. In seconds, all her worries vanished.

Click Here to Read the Reuters Series on Drugs and Newborns

After about a week, Yeager decided to stop using. But this “slip up,” as she describes it, presented a dilemma: Two friends who quit cold turkey had gone into premature labor. With heroin still in their bodies, the state seized their babies. Fearing this, she obtained a legal prescription for Subutex, a drug used to treat opiate addiction.

In mid-December 2014, Yeager went into premature labor anyway. Her baby, Kennedy Jade Yeager, faced a harrowing first few months. Born hooked on the drugs her mother had been taking, Kennedy began an agonized withdrawal.

Federal law requires states to have plans to identify and protect babies like Kennedy, not just during their hospital stays but after they are sent home with their mothers. Most states fail to comply, Reuters found, leaving at risk thousands of children born drug-dependent each year.

West Virginia is an exception. Along with the District of Columbia, it’s one of no more than nine states that insist doctors report every case to child protection workers — not necessarily to remove babies, officials say, but to keep them safe while helping their mothers.

A memo issued early last year by the state’s Department of Health and Human Services explains why each case must be monitored. It refers to a “rash” of child fatalities involving babies whose mothers had been using drugs that were legally prescribed to them. The memo tells social service and child welfare workers that “it is often impossible to know” whether a mother is “actively involved in a treatment program or if the parent is abusing the prescribed drugs … and unable to properly care for a newborn.”

That’s why the state says it wants to assess all cases in which a child tests positive for drugs.

“All newborns are extremely vulnerable,” the memo says, “as 100 percent of their livelihood is dependent upon their caregivers.”

It’s that reality that inspired a charity in nearby Huntington to create a program designed to do more than simply wean newborns off drugs. Healthcare and social workers also train mothers fighting their own addictions to care for the difficult babies. Experts say only a handful of similar programs exist nationwide.

At the hospital, Yeager was among the first to be offered entry into West Virginia’s pilot program, which began in October 2014. To enroll, she had to sign Kennedy over to state custody. If both baby and mother successfully completed the program, the social worker promised, Yeager would get Kennedy back.

“A Crisis Right Here"

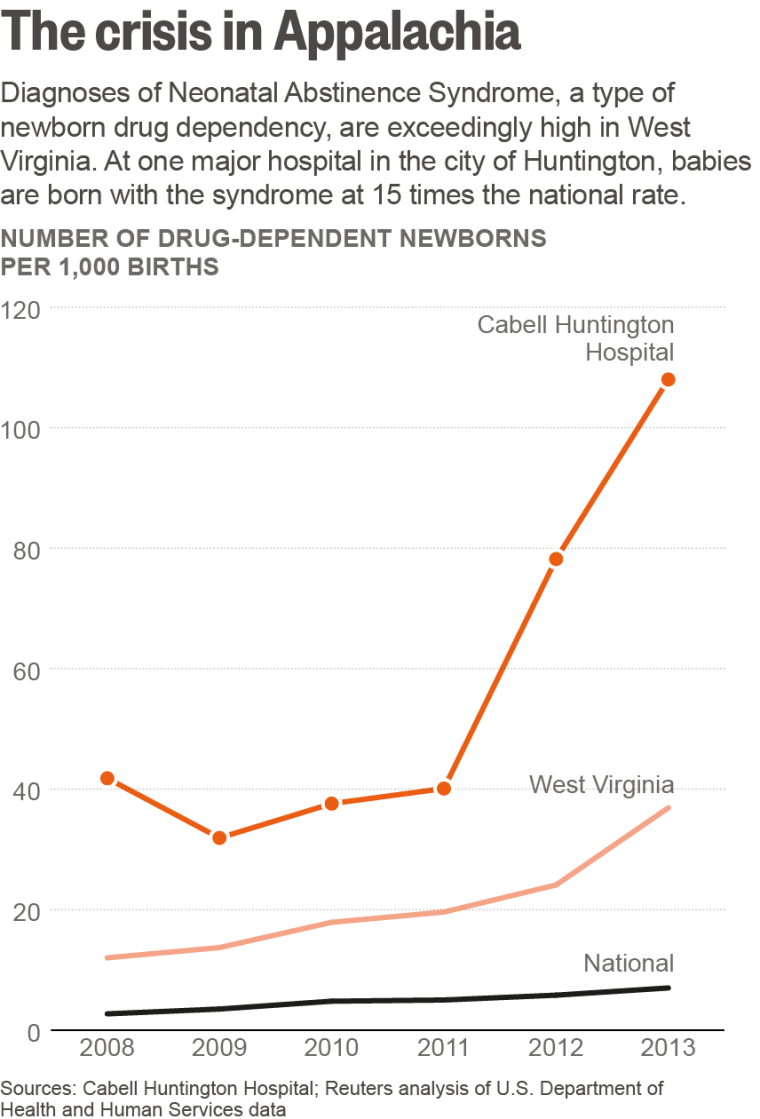

Nationally, nearly 7 out of every 1,000 babies born in 2013 were diagnosed with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, a consequence of drug dependence among newborns, according to a Reuters analysis of federal data.

In West Virginia, the rate is about five times higher — 37 of every 1,000 babies. At Cabell Huntington Hospital, where Kennedy was born, 108 of every 1,000 babies born in 2013 were diagnosed with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Last year, the rate at Cabell Huntington increased to 139 out of 1,000.

The pace hasn’t slowed this year, nurses said. In one 24-hour period last month, six babies were born in drug withdrawal. On average, the hospital handles eight births a day, which includes both healthy and sick infants.

“Even in your darkest, deepest imagination, you can’t imagine their agony,” said neonatal nurse Sara Murray. “You think you might know what one of these tremoring and screaming babies sounds and looks like, but it’s nothing like a colicky baby. We have some who scream as if their limbs are being ripped off.”

The problem first became acute at Cabell Huntington in 2011, doctors said. By then, newborns withdrawing from drugs occupied two-thirds of the neonatal intensive care unit, which has 36 beds. That left little room for newborns with life-threatening conditions unrelated to a mother’s drug use.

“We are the large regional hospital in a three-hour radius, and we were turning down sick and needy babies from other hospitals,” said Sean Loudin, the neonatologist who treated Kennedy.

In 2012, the hospital created a second neonatal unit just for babies going through withdrawal. Those 16 spots soon filled, too.

The kernel of a solution came when two veteran neonatal nurses, Murray and Rhonda Edmunds, explained to a hospital volunteer that the babies would heal faster if they lived off-site, somewhere far from buzzing machines and bright lights, and where mothers could learn parenting skills. The volunteer, local activist Mary Calhoun Brown, got to work.

“Lots of friends at church go on overseas missions, and no disrespect to them, but we have a crisis right here at home,” Brown said. Her first call was to Evan Jenkins, then a state senator and now a U.S. Congressman.

The nurses developed a medical plan. Jenkins devised ways to navigate state, Medicaid and insurance bureaucracies. Brown founded a charity to manage the facility and raised startup funds from coal industry foundations. A podiatrist’s widow donated her husband’s vacant office building.

Lily’s Place opened last fall with a mission to treat newborns and mothers in a nonjudgmental fashion. Soon, babies began arriving.

Difficult Times, Hard Choices

Yeager knew the dangers opiates pose. At least five high school friends had overdosed and died. Two women she knew had been jailed shortly after giving birth, one for accidentally smothering and killing her child while in a drugged stupor.

Yeager also understood how difficult motherhood can be. Seven years earlier, while in high school, she’d given birth to a girl. Yeager said she did not get high during that pregnancy, but when her child was a toddler, she began abusing prescription painkillers. Yeager became homeless and transferred guardianship of the child to the father’s parents.

She didn’t want to lose another baby.

She was already on probation for a crime: Stoned on Xanax and methamphetamine in March 2012, Yeager had helped two men rob an elderly man of $200. Police caught the three hapless addicts hours later.

Yeager pleaded guilty and was sentenced to two years’ probation in spring 2013. Within months she tested positive for morphine and marijuana, skipped probation meetings and fled to Ohio. She was arrested in late 2013 and jailed until early 2014, when she began rehab and went to live in the apartment for female addicts in Charleston.

During recovery sessions nearby, she met Donnie Gooding, a former coal miner who had just served a short jail term for manufacturing meth. He was nine years older and cocksure. She loved his tattoos — he had the word LUNATIC stenciled across his neck — and the passion with which he pursued her. Soon, she became pregnant. For a while the couple dreamed of a sober future with a healthy baby.

But by late summer 2014, Gooding violated probation and was sent back to prison. That’s when Yeager relapsed and then started on Subutex.

A short while later, during her eighth month of pregnancy, Yeager decided to visit her grandparents in Barboursville, about an hour away. Their house happened to be a few miles from Cabell Huntington Hospital and Lily’s Place.

Four Pounds, Six Ounces

Yeager went into labor during the visit, and her grandfather rushed her to Cabell Huntington. Kennedy was born there on Dec. 19, 2014, four weeks premature.

She weighed just 4 pounds, 6 ounces. On a chart, a nurse rated Kennedy generally healthy but noted that she seemed hyperactive and jittery, the first hints of withdrawal.

About half of the babies born to mothers who take opiates during pregnancy begin life the way Kennedy did. While she was in the womb, Kennedy’s brain had been stimulated by drugs for months. But at birth, when the umbilical cord was cut, the opiate supply suddenly stopped, creating a chemical imbalance and abnormal behavior.

Babies like Kennedy arrive in the world irritable and hyperactive, making them far more difficult to keep calm than typical newborns. The tiniest noises can trigger inconsolable wailing. They are frightened easily, often by their own movements, even extending a leg. They can suffer involuntarily spasms and fits of yawning and sneezing.

Feeding can be a struggle. Unable to focus, the babies often choke or cough after a few sips of formula or breast milk. The sensation can panic them. Kennedy, typical of newborns in withdrawal, suffered from explosive diarrhea. Painful rashes followed.

Two days after birth, Kennedy was transferred to Cabell Huntington’s special neonatal unit for babies in withdrawal. Yeager was discharged.

“It didn’t really hit me until I got home and she wasn’t with me,” Yeager recalled. “Then I had all the guilt and regret. I’m a terrible mother. Why would I do this?”

Kennedy began a withdrawal protocol — decreasing micro-doses of methadone, a heroin-replacement drug — that lasted five weeks. When Yeager visited the hospital, she found it hard to keep Kennedy calm, in part because the infant shared a room with two other wailing, drug-dependent babies.

A few days later, Yeager was approached by Angela Davis, a Lily’s Place social worker. Davis invited her to put the baby in the new facility. “She explained that it was just like a hospital but Kennedy would get her own room,” Yeager recalled.

The offer included requirements for mother as well: Yeager would have to visit Kennedy six times a week, help the nurses care for her baby, take parenting classes, meet regularly with the social worker, and attend her own addiction recovery sessions. Most important, she needed to learn her newborn’s “stress cues” and how to address them. Yeager promised to do everything.

“Do Not Abuse Your Baby"

Kennedy’s condition was charted with a widely used medical scale to tally the frequency, length and severity of symptoms — high-pitched cries, tremors, sweating, poor sleep. A score of 8 or higher means a baby’s condition is considered severe.

After two weeks at the hospital, Kennedy was transferred to Lily’s Place. On her first day there, her average score was 7. Within days, her score climbed to 10. At times it hit 17. Kennedy continued to sweat and cry excessively. Every few days, she shook with tremors.

Kennedy’s average score did not drop below 8 until her third week at Lily’s Place. Although doctors took the baby off methadone, they warned Yeager that Kennedy’s withdrawal would continue for months.

On Kennedy’s final day at Lily’s Place — she was 5 weeks old — Yeager was shown a video prepared by Loudin, the neonatologist.

“You are not taking home a completely normal newborn infant,” the doctor said in the video. “You have to recognize your baby is going to have bad days. At these times it is vital for you to keep yourself calm and not do anything that can harm the baby. Please, if you find yourself frustrated, the safest thing you can do is put your baby in a car seat, put it on the floor and walk away for a few minutes and collect yourself. Do not shake your baby. Do not abuse your baby.”

A Fresh Start

For Yeager, her grandparents’ home in Barboursville, a village near Huntington, had long been a refuge. She spent years growing up there and was welcomed back in her early 20s, even after she repeatedly stole from them and a boyfriend once assaulted her grandfather.

The grandparents agreed to drive Yeager to recovery meetings and pediatrician appointments. But they insisted that Yeager would have to care for Kennedy 99 percent of the time.

During the first few weeks at their home, Kennedy’s tremors continued. Often, she was cranky. Yeager said she did her best to calm Kennedy, applying tips from Lily’s Place, such as swaddling the baby snugly and darkening the room.

“It was stressful … I’d be lying if I said I didn’t think about getting high,” she said. “But then I realized how far I had come and where I wanted to go, and that if I did that, Kennedy could be sent to a foster home, and anything could happen to her there.”

Yeager’s own recovery appeared to accelerate late this summer, after Gooding was released from prison. They married, and she began taking college courses online. Gooding got a steady construction job and helped Yeager pay off fines so she could get a learner’s permit to drive.

Recently, the couple rented a tiny apartment near Yeager’s grandparents. She takes a prescription drug to help her resist her heroin cravings. Both say they are off illegal drugs. In September, Yeager took Gooding’s last name. In October, their baby did, too.

Since Lily’s Place opened late last year, 66 babies have been weaned off drugs there. The fates of their mothers vary. Social worker Davis estimated that 80 percent were doing well on the day their baby was discharged; they were either off drugs completely or in recovery as part of a doctor-ordered prescription protocol. Two have overdosed and died.

But all 66 babies are alive.

This fall, Kennedy hit milestones for normal infants of her age: By 8 months, she could sit up, crawl and hold things in her hands. Her weight climbed to 19 pounds. She started pulling herself upright while balancing on the side of a couch or chair, a precursor to her first steps. And she began to smile in elevators and restaurants, no longer frightened by noise and bright light.