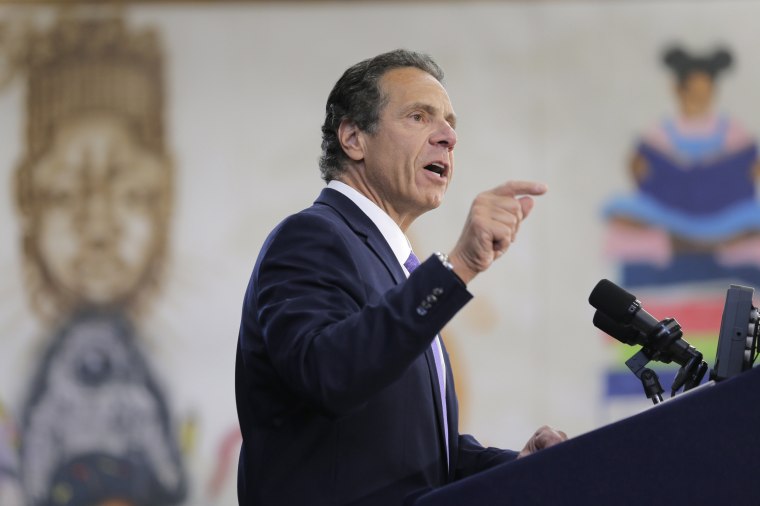

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a longtime antagonist of the National Rifle Association, said recently that he had discovered a new vulnerability in his foe: legally dubious insurance products the organization sells to its members. He cut off the business in New York and called on other governors to follow his lead, part of a broader campaign against the powerful gun-rights advocacy group.

While at least two states have opened investigations into the NRA’s insurance practices, the tactic probably won’t have much impact. The NRA made less than $2 million from its insurance programs in New York since 2000, according to recent court filings. And the NRA apparently took in less than $12 million annually from those programs nationwide — a tiny drop in the organization’s $378 million annual revenues, according to a 2016 financial statement.

In other words, it’s going to take a lot more to hobble the gun-rights giant.

But Cuomo believes he has a potential answer to that, too.

This spring, riding a corporate backlash against the NRA following the massacre of 17 people in a Florida high school, Cuomo had his Department of Financial Services issue a warning letter to all of the state’s banks and insurers: If you do business with the NRA, it is time to reconsider, or risk harming your reputation.

In response, the NRA, founded in New York in 1871, sued Cuomo, saying the guidance letter and other regulatory actions have scuttled potential contracts for its banking services and its own insurance coverage — putting a chill in a market that could one day make it difficult to operate. Cuomo’s actions are part of a decades-long political vendetta against the NRA, the group says.

While the NRA has shown signs of financial troubles, their claim of potential doom may be bluster aimed at rallying supporters to donate more money, experts say. Cuomo, too, may be blustering; he is in a hotly contested primary against a left-of-center Democratic challenger, the actress Cynthia Nixon. But if his financial sanctions against the NRA catch on in other blue states, experts say it could make things more difficult.

“They have some long-term financial questions, and that would add to them,” said Brian Mittendorf, who heads the accounting department at Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business and studies the NRA’s finances.

On Wednesday, Washington State became the first state to respond to Cuomo’s letter when its insurance commissioner announced he would investigate the NRA “for advertising a potentially misleading insurance policy.”

The NRA said it was surprised by the announcement, because it had already made changes to Carry Guard in response to discussions with Washington regulators, and was given assurances that the program did not break any laws or regulations.

California’s Department of Insurance is also conducting an investigation into the administration of the NRA’s insurance products, including Carry Guard, although that review began months ago, an agency spokeswoman said. The NRA said Wednesday that the Department of Insurance had not contacted them.

Many of the NRA’s issues are the result of its increased spending surrounding the 2016 elections, including record support of President Donald Trump. Its membership revenues were flat during that time, despite an attempt to sell more lifetime memberships. The result was a drop in net assets of nearly $40 million, Mittendorf said, citing audited NRA financial statements.

But the NRA has plenty of time to resolve those issues, Mittendorf said.

“My impression is that people are overreacting to statements involving the organization’s future being in jeopardy in the short run,” Mittendorf said.

Samuel Brunson, a professor at Loyola University Chicago Law School who studies tax and nonprofit organizations, agreed. New York’s guidance letter, and Cuomo’s push for other states to crack down on the NRA, could be damaging, but not disastrous, he said.

“If banks or insurance companies refuse to work with the NRA, I could see how that could hurt the NRA,” Brunson said.

The legal dispute stems from the NRA’s post-election attempts to expand its membership insurance programs. In April 2017, just before convening its annual meeting in Atlanta, the group announced that it would enter the growing market for insurance coverage for people who shoot their guns in self-defense. The NRA embarked on an aggressive marketing campaign to drum up business for the product, called Carry Guard.

The new program caught the attention of Everytown for Gun Safety, a gun-control advocacy group born in the aftermath of the 2012 massacre of schoolchildren in Newtown, Connecticut. Everytown said it believed the NRA was illegally acting as an insurance broker, and complained to authorities in New York.

Everytown found a sympathetic ear in Cuomo and his top insurance regulators, who launched an investigation. The state Department of Financial Services decided that the program indeed broke the law, saying it covered gun owners’ “acts of intentional wrongdoing.” In May, the agency fined two insurance companies that backed Carry Guard — Lockton Companies and Chubb — and shut down the program in New York, along with a variety of other insurance products the NRA sold to members. The Department of Financial Services says its investigation of the NRA’s marketing of Carry Guard remains ongoing.

Responding to New York’s letter to the financial community, the NRA accuses Cuomo of “political blacklisting” and violating its First Amendment rights to advocate in support of gun rights. Cuomo has acknowledged he wants to damage the NRA’s business.

“If they have less money to bully and threaten politicians into irrational positions, I'm not going to lose any sleep over that,” Cuomo said on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe” on Monday. “And if they went away, I would offer my thoughts and prayers, Joe, just like they do every time we have another situation of innocents losing their lives.”

Cuomo’s aggressive stance against the NRA is unusual but could be effective, said Daniel Schwarcz, an expert in insurance law and regulation at the University of Minnesota Law School.

He pointed to the Department of Financial Services’ guidance letter, which relied on the concept of “reputational risk” — basically, how a company’s actions influence the way it is viewed in the marketplace, and how that affects its ability to remain in good financial health.

Schwarcz said it could be a stretch to show that working with the NRA significantly changes a company’s reputational risk. But financial institutions are typically very careful not to anger regulators, who wield a tremendous amount of power over them.

“If it’s simply a matter of not writing a policy that might generate a small amount of revenue, the prudent thing to do might be, ‘Let’s not even get close to that line,’” Schwarcz said.

Experts also expect more governors to answer Cuomo’s call to join him in cracking down on the NRA’s membership insurance programs, including Carry Guard, which remains available in every other state. New York, which regulates many of America’s most powerful financial institutions, typically sets the tone for regulators across the country, they said.

NRA lawyer William Brewer III said in a statement that the organization considered Cuomo’s campaign to persuade other states “regrettable and misguided” but believed it was his right to do so.

“We believe what he cannot do, as a public official subject to the First Amendment, is coerce third parties to boycott an organization whose political speech he dislikes,” Brewer said.

The NRA has separately sued Lockton, accusing the insurance underwriter of abandoning it under pressure from New York authorities. Lockton has blamed the NRA for courting trouble, including an “inflammatory marketing campaign” for Carry Guard.

But the NRA seems to thrive on controversy: Following the Florida shooting, as corporations severed ties and New York regulators bore down, donations flooded into the NRA’s political action committee, according to an analysis by the Center for Responsive Politics.

While the future of Carry Guard may be in doubt, its story reflects the NRA’s “ability to blend political and market power to protect and promote gun rights,” said Jennifer Carlson, who researches gun politics at the University of Arizona, in an email.

David Yamane, a Wake Forest University sociology professor who studies gun culture, said Cuomo’s attacks, and the NRA’s claims of potential disaster, could only serve to exacerbate the polarization over guns in America.

“Most political officials don’t talk about putting lobbying groups or non-profit organizations out of business through the legal system,” Yamane said. “That’s the more jarring aspect of this, and won’t do anything to move us forward in terms of our discussion about guns.”