Katrina Eaton could hear the emotion in her 12-year-old son Isaac's voice when he came home and talked about what he had learned in school.

His teachers at Carver Middle School in Tulsa, Oklahoma, had taught that day about a race massacre in the city a century ago, when a white mob descended on Tulsa's Black Greenwood neighborhood, killing hundreds of people, destroying many successful businesses and leaving thousands homeless.

The instruction was a lesson for Eaton, too.

"I mean, I've learned more because of what his school has taught him," said Eaton, who is white. "We all have to be talking about the facts and what happened in the past."

As the nation prepares next week to mark the 100th anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre — considered one of the worst incidents of racial violence in the country's history — schools in Oklahoma are pushing to ensure that residents grow up knowing about the tragedy. The effort is an about-face after what many say was years of silence or inadequate education about the topic.

"We have to teach this and face the ugliness of what I believe we've been too ashamed to talk about in the past," said Joy Hofmeister, superintendent of the state Education Department. "We cannot turn our back on the truth."

Hofmeister said she grew up in Tulsa and didn't learn about the massacre until she was an adult.

The state has included the Tulsa race massacre as part of its academic standards since 2002, but the standards didn't say what teachers should teach and how they should teach it, leading to little, if any, time's being spent on the topic.

That changed in 2019, when the state Education Department embedded what was to be covered and how in the requirements of the state's academic standards at different grade levels, Hofmeister said.

The Education Department has since also provided additional resources to help teachers impart the lessons.

Sam Dester taught the race massacre to 11th graders in U.S. history and advanced placement U.S. history at Charles Page High School in Sand Springs this year.

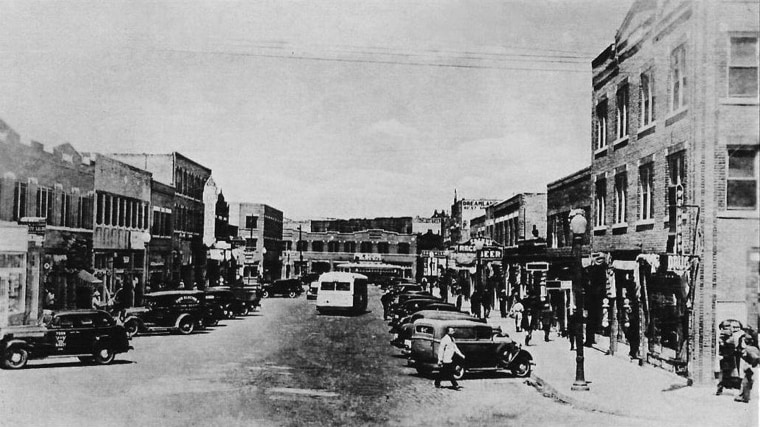

He said he required students to look at firsthand accounts and photographs, such as write-ups from the American Red Cross and other organizations that were on the ground. Then he asked them to share their thoughts, feelings and general reactions.

"When you see these photographs of what looks like Europe after World War II, I mean, really, these buildings that are just shells," he said. "Then they start thinking to themselves about how you can just hop on the highway and you could be right there in five minutes — there's kind of like a wave of shock."

He supports teaching the massacre in schools and giving teachers incentives to teach it by making it part of the state's academic standards.

"I mean, the last time you take world history might be as a 10th grader. For the rest of your life," he said. "And so any time that history is reinforced for you, it's really important."

Melani Ford didn't shy away from teaching her preschool students about Greenwood this school year at Cleveland Bailey Elementary School in Midwest City. She said she told them that a long time ago in Tulsa, there was a town and some people burned it.

"I say that happened here in Oklahoma and we haven't recovered from it, but we're trying to do better about it," said Ford, 33, who is Black.

Other teachers may be hesitant to introduce the district or the historical event to young children because it's such a "heavy topic" and they don't know how to talk about people being killed, Ford said.

But she said that for younger students, adults can begin by introducing broader ideas of what happened and saying, "We're not happy about it."

"History is not always beautiful, but we need to know what happened and why it happened and know that we can do better," she said. "To understand that, yes, there was a group of people who did that, and we need to make sure that we don't repeat ourselves, I think that's important to learn, no matter the age."

But there is concern that some of the progress in teaching a more complete version of the state's history could be erased.

Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt this month signed a law that bars teaching concepts or courses that would cause people to "feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress" because of their race or gender. It also bans promoting concepts such as that anyone, "by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously."

"Now more than ever, we need policies that bring us together, not rip us apart," Stitt said in a statement on Twitter. "As governor, I firmly believe that not one cent of taxpayer money should be used to define and divide young Oklahomans about their race or sex. That is what this bill upholds for public education."

The law takes effect July 1.

Teaching the Tulsa race massacre and the Greenwood District remains part of the state's academic standards in state and U.S. history. Critics of the law worry about the "chilling effect" it could have on educators who are trying to teach complicated historical topics involving race or gender.

"It's for sure twisting the knife in the wound, so to speak," Eaton said about the timing of the law.

State Rep. Monroe Nichols, who represents the Greenwood District, said the law "puts an enormous pressure on educators to get it right, but it's unclear what getting it right really means."

"I think the law was written in such a way that there's so much ambiguity," said Nichols, who is Black. Nichols resigned from the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Commission this month because of the new law.

Speaking about his 13-year-old son, who has learned about the massacre in school, he said, "I think it's super important to understand these things not just to be educated about it but to understand what it means, as far as what we have to do moving forward."

Naomi Andrews, a mother of four children in sixth through ninth grades, said: "They're creating a world that's not based in reality. They're hiding information from students and the teachers who would teach it."

Susan Foust, a recently retired librarian who helped teachers develop the fifth grade curriculum for teaching the race massacre at Emerson Elementary School in Tulsa, agreed.

"It needs to be told. And the teachers have to be the ones that teach it," she said. "To tell us that we can't talk about racism and we have to make it so that nobody feels guilty — I mean, there has to be some understanding of how human nature is and how communities have to support each other."

CORRECTION (May 27, 2021, 11:20 p.m. ET): A news alert that was issued for this article mischaracterized a new state law in Oklahoma. It would bar teaching of material that would cause students to feel discomfort because of their race; it would not make permanent the teaching of the Tulsa massacre.